The High-Stakes Lawsuit Against The Internet Archive (And Why It Matters For You)

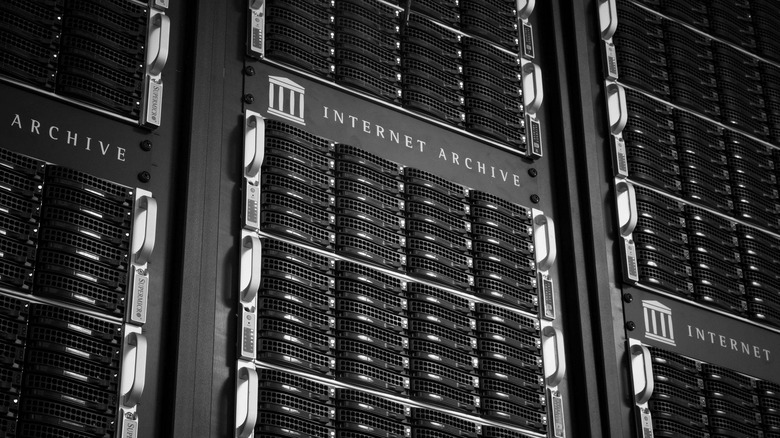

Exactly what The Internet Archive represents to you probably depends on when you discovered it and subsequently, how you've used it. The massive non-profit digital library is probably best known for The Wayback Machine, it's cache of massive swaths of web pages going back decades. At a time when all sorts of websites and/or their article archives have been deleted, covering outlets ranging from CNET to Gawker to The Messenger to MTV News among others, it makes sense, but it's far from the entirety of the Archive. It also features not just sections for users to upload historical recordings and documents, but also other Archive-curated collections like a historical software collection and numerous books and periodicals that it offers up like a more traditional lending library.

In theory, the idea that the Archive holds itself out to be a library should offer it some protections. In practice, it's a lot more complicated as a lot of the legal theories around the digital library's fair use arguments have long sat untested. However, that's changing thanks to an ongoing lawsuit from various major publishers taking aim at the aforementioned lending library in particular. As that case has made its way through the federal court system, there have been wins and losses on both sides, with the theories behind The Internet Archive finally being tested, sometimes to its detriment. Let's examine when and why the publishers sued the Archive, how it's gone so far, and how the case looks going forward.

[Featured image by Ralf Muehlen via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped | GNU FDL]

Who sued The Internet Archive and why?

In March 2020, as the U.S. was locking down due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, The Internet Archive drew a attention to itself with a major announcement: It was removing the restrictions from its "Open Library" digitized book collection, which normally allowed one lender at a time per physical copy owned by the Archive. The Archive was clear that "The National Emergency Library" would only be in effect as long as the national state of emergency was in effect, but publishers were unmoved, with the Authors' Guild and Association of American Publishers both condemning the move. The Guild previously condemned the Archive's "controlled digital lending" — CDL for short — as "neither controlled nor legal" in a January 2019 blog.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, four major publishers sued the Archive in June 2020: Hachette, HarperCollins, Wiley, and Penguin Random House. "Despite the 'Open Library' moniker, IA's actions grossly exceed legitimate library services, do violence to the Copyright Act, and constitute willful digital piracy on an industrial scale," reads the complaint. A few lines earlier, the publishers alleged that "With just a few clicks, any Internet-connected user can download complete digital copies of in-copyright books from Defendant," which they later clarify refers to copies that are outfitted with Adobe Digital Editions copy protection. At its heart, though, the argument was that CDL has no basis in established fair use caselaw and "CDL is based on the false premise that a print book and a digital book share the same qualities."

How did the Archive respond?

The Internet Archive is being represented in the lawsuit by the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation, which maintains a webpage devoted to updates on the case, and that includes the Archive's July 2020 answer to the complaint. "Through the Internet Archive, people who do not live in world capitals can access the same cultural and informational resources as those who do," reads the answer. The basic argument was that the Open Library collection was acquired legally and that, using CDL, there was no practical difference between the Archive's lending library services and those of a traditional library loaning out physical books.

"Patrons can borrow and read entire volumes, to be sure, but that is what it means to check a book out from a library," the answer continues. "As for its effect on the market for the works in question, the books have already been bought and paid for by the libraries that own them. The public derives tremendous benefit from the program, and rights holders will gain nothing if the public is deprived of this resource." As for the National Emergency Library, the Archive didn't do much beyond point to the obvious, that numerous traditional libraries' collections of the books in question were unavailable at the time and that the plan was always for it to be temporary. "Twelve weeks later, other options had emerged to fill the gap, and the Internet Archive was able to return to the traditional CDL approach," it argued.

Who else is supporting the Archive?

The Electronic Frontier Foundation isn't alone in formally coming to the Archive's defense. In July 2022, a group of 17 copyright scholars filed an amicus (Latin for "friend of the court") brief supporting the Archive as an interested non-party. This group included law professors from prestigious universities including Texas A&M, Georgetown, the University of Georgia, UC Berkeley, and New York University, among others.

"Such a drastic shift in who controls library lending would fundamentally change not only how libraries work but also their relationships with their patrons and collections in the digital era," the brief argues. The gist was that the plaintiffs' reading of the Copyright Act was overly narrow, sidestepping how copyright has gradually evolved in common law. Specifically, the professors noted that "incidental reproductions are often necessary" in the course of running a library, and that, with CDL limiting distribution to numbers in line with exactly what the Archive could physically loan out without legal objections, that's all the scans are. In other words, the scholars asserted that CDL was simply in the process of becoming the latest in a long line of fair use interpretations throughout history.

Also filing similar amicus briefs on the Archive's behalf was a trio of library associations and the Authors Alliance. "Books loaned via CDL are distinct from licensed eBooks," wrote the library group. That brief also noted that CDL fills a gap when specific books or editions of books don't have official eBook editions.

Who else is siding with the publishers?

The Internet Archive wasn't the only side of the lawsuit to have friend of the court briefs filed in their defense. The same can be said for the publisher plaintiffs, as well. This included a consortium of international publishers that backed the arguments of its domestic counterparts. "U.S. courts are required to apply the defense of fair use in a manner that satisfies the required standards established by international copyright and related rights treaties described infra, and any exception that purports to enable [the Archive]'s copying and making available of protected eBooks worldwide on an immense scale fails to do so," it reads, arguing that spillover outside of the U.S. was a significant concern.

The Copyright Alliance, meanwhile, described the Archive and its supporters as "espous[ing] a distorted theory of fair use." In a footnote, it singled out the National Emergency Library as flying in the face of the Archive's core defenses of CDL, since it had shown a willingness to break the one book, one loan promise. It further argued that libraries' rights to make copies were explicitly balanced by copyright holders' interests under the law, with only Congress able to expand those rights to digitization and digital lending. The Authors Guild and many other writers' groups joined the fun in a separate brief arguing that the court should not find CDL to be fair use because it would give excessive power to any entity that described itself as a library.

Does it matter that The Internet Archive calls itself a library?

The Archive's arguments revolve around being a library, but...what does that mean? In 2018 at Gizmodo, I tried to understand exactly how much legal exposure that the nonprofit faces, albeit in the context of removing Wayback Machine caches due to DMCA takedown requests. "The fair use defense in this context has never been litigated," said Annemarie Bridy, a copyright scholar and law professor who's now Google's Senior Copyright Counsel. "You can understand why their impulse might be to act cautiously even if that creates serious tension with their core mission, which is to create an accurate historical archive of everything that has been there and to prevent people from wiping out evidence of their history."

Brandon Butler, then of the University of Virginia, meanwhile, identified an even thornier issue: There is no clear legal definition of what a library is despite the protections afforded to libraries under copyright law. This has rarely been tested, so copyright holders would historically hem and haw about the possibility of faux libraries, just as the Authors Guild would later argue in its amicus brief. "They often raise up a stand that there will be faux libraries, that they'd call themselves libraries but it's really just a haven for piracy," Butler explained. "That specter of the sort of sham library really hasn't arisen." In other words, the specific mechanism of CDL isn't the only uphill climb for the Archive in defending the publishers' lawsuit.

How have the courts ruled so far?

In July 2022, the plaintiffs and defendant filed motions for summary judgment, putting the case in the hands of Hon. John G. Koeltl. Come March 2023, Koeltl ruled for the publishers, seemingly setting the stage for a dangerous precedent. "At bottom, IA's fair use defense rests on the notion that lawfully acquiring a copyrighted print book entitles the recipient to make an unauthorized copy and distribute it in place of the print book, so long as it does not simultaneously lend the print book," he wrote. "But no case or legal principle supports that notion. Every authority points the other direction." Koeltl added that the Archive was free to use the book scans in ways that courts have affirmed as fair use, such as the Google Books precedent allowing Google's implementation — full text searches revealing limited previews — to stand after a lawsuit from the Authors Guild.

Later in 2023, the Archive appealed, arguing CDL "is noncommercial, transformative, and justified by copyright's purposes" as a digital modernization of traditional lending library services. The publishers' brief followed in March 2024, saying "there is nothing transformative about IA's CDL practices because it does nothing 'more than repackage or republish' the Works." citing the Fox News v. TVEyes precedent. As of this writing, the appellate panel hasn't ruled, but the Archive's lawyers told Ars Technica after June 2024's oral arguments that the judges seemed much more engaged by their case than that of the publishers'.

What does this mean for everyone?

The Archive prevailing on appeal would have obvious benefits, although the prospect of the publishers escalating the case to the Supreme Court is always a possibility. In June 2024, as a consequence of the initial district court ruling, the Archive announced that it had to remove 500,000 books from The Open Library, and one would think they'd return if the appeal goes the right way. Presumably, a victory for the Archive would lead to the Open Library returning to its previous state.

But there are the broader implications for fair use precedent. If the courts rule in the Archive's favor, CDL becomes enshrined in the law as legal via the precedent. Would other libraries, whether public or at universities, seek to implement their own versions? Would the Archive offer infrastructure for libraries to sync up their physical catalogs and offer CDL digital versions of their holdings? If the Archive loses, the Open Library most likely settles into being another Google Books, offering book searching services but not borrowable full copies.

Beyond that, it depends on how the precedent gets cited going forward. It's not as if CDL has been widely used by non-Archive entities, so if the Archive loses its appeal, then that probably doesn't change. If the Archive wins, then there are a lot of options opened up that copyright holders will probably litigate to the end of the earth to have such a ruling be read as narrowly as possible.