How Information Is Driving The Future Of Car Safety: An Engineer Explains

Data is often referred to as the oil of our modern age. With the proliferation of technology it's now a resource that flows all around us, but which is not extractable without costs to privacy. When refined and harnessed, though, it is a source of incredible power to enable everything from more efficient global trade to decisions about what gets published on this very website. Yet when people think about data, they tend to envision more ephemeral applications like social media. The truth is that data now shapes not only the digital world but also the physical one. It's currently driving advances in car safety that will shape the way we experience cars, the road, and the act of driving itself.

To get a better understanding of what we can expect from the data-driven future of motor vehicles, SlashGear spoke with Dr. Laine Mears, the Chair of Automotive Manufacturing at Clemson University. He spoke about the importance of data for powering many safety features drivers now take for granted, as well as what the future of data-driven approaches to car and road safety might look like. Of course, just as data collected for big tech, data collected from cars also carries privacy concerns. Here's how information is driving the future of car safety.

Data is driving advances in safe car design

According to automotive manufacturing expert Dr. Laine Mears, data has already improved the safety of car travel. "Cars today are really safe," he said, "due to technologies such as emergency braking and steering to avoid crashes, and airbags and high-performance material designs to protect occupants when a crash does occur."

Data from crashes helps make cars safer as it can help engineers figure out which vehicle weaknesses are leading to the most fatalities, ensuring future car designs can be safer. Even so, many people still die each year because of car accidents. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) reports that in 2022 alone 42,514 people lost their lives due to crashes, and that's just in the United States. Incidents not only imperil or take lives, they're also costly. Based on data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, the IIHS puts the annual economic cost of crashes at $340 billion, even while the data shows that fatal crashes declined heavily over the past half century, despite more cars than ever before on the road.

While 1979 saw the peak of American motor vehicle deaths, totaling a heartbreaking 51,093 fatalities, 2011 saw the lowest number with 32,479 lives lost. That's because information has allowed car companies to design safer vehicles while giving lawmakers and regulators the understanding they need to develop robust road safety protections. Still, some cars are safer than others. Unfortunately, as recorded by The New York Times, the years since have seen a shocking rise in U.S. traffic deaths as much of the rest of the world continues to become safer for motorists and pedestrians. Some have speculated that, since a shocking number of the increased deaths have been pedestrians struck by motorists, the surge in fatalities is the result of a lack of pedestrian access to walkable cities.

Data is helping us drive safely

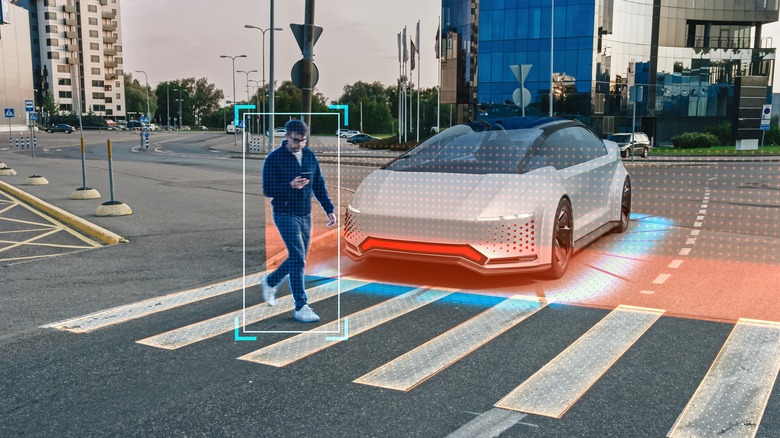

Aside from making the physical design of cars safer, information could power innovations in communication between people, cars, and the driving environment, says automotive manufacturing expert Dr. Laine Mears. "The future in my mind is better communication and control from the environment and communication with other vehicles, in order to give better information to each vehicle," he said. "What if you already knew that highway traffic over the next hill was at a dead stop or that the truck next to you needed to swerve across your lane to get off at the exit? It would be a much safer (and less stressful) world."

In many ways these ideas are already in practice, just not at the vehicle level. Applications like Waze and Google Maps already let users communicate with one another on the road by flagging issues like upcoming traffic jams, speed traps, and crashes. The navigation software then factors these user-submitted hazards and slowdowns into its route calculations. Nevertheless, it's not quite at the point of Mears' vision. If we take his example about knowing when a truck next to you needs to cross your lane, we do have a technology for this, it's called using your blinkers. However, imagine a more intelligent alert system aware of the actions of nearby vehicles, able to notify even those who don't see the blinker flashing.

Data is crucial to the future of self-driving vehicle safety, and it's at the heart of why the progress of autonomous driving has reached a plateau. This is because self-driving vehicles are currently not safe enough to fully deploy, and they therefore cannot collect the information required for the learnings necessary to improve their safety.

Information about safety is helping the world design safer roads

Another way information can be valuable to the future of car safety is in the development of roadways. This can take many forms, with the most basic being the use of driving data to guide city planners and others involved in engineering new roads. By understanding how people behave while driving, it is possible to figure out which kinds of roads and traffic controls are the safest for not only motorists, but also cyclists and pedestrians. For example, rather than setting a low speed limit or installing traffic lights in a place where pedestrians often walk, roads can be narrowed or curved into odd shapes, calming traffic and forcing drivers to slow down to safe speeds. As an even smaller and more ingenious example, safety experts have found that giving pedestrians a three to seven second head start on a crossing, before the light turns green for vehicle traffic, reduces related accidents by 13 percent because it makes pedestrians more visible to drivers.

Unfortunately, although countries like the Netherlands have successfully implemented simple, cheap, and data-driven solutions to traffic related deaths and injuries, the United States has stubbornly lagged behind, resulting in a fatality rate far higher. Not only is American traffic often deadly, but it's also frequently inefficient, resulting in a nation of frustrated drivers alongside the imperiled cyclists and pedestrians. One such example is the common policy of expanding roads — despite the fact that adding lanes does very little to improve the flow of traffic — rather than implementing cheaper, more efficient solutions.

The dark side of car data

It's clear there are many ways that car data can help keep us safe on the road, but that doesn't mean it's all upside. Newer cars equipped with advanced sensors that detect driver behavior can abuse your car data and sell it to third parties, including insurance companies.

As reported by The New York Times, one man was shocked to find out that his Chevrolet Bolt had recorded every trip he'd taken with it over a six month period — including how fast he'd gone and how many times he'd accelerated or braked hard — and sent the data to LexisNexis, a data broker. LexisNexis then sent that information, in the form of a detailed report full of data-driven insights, to his insurance company, who in turn raised his rates by nearly a quarter. His data was captured by the OnStar Smart Driver feature, built into his Bolt. The same article notes that many people are unaware of such data collection features in their vehicles, or that they're turned on, and can accidentally opt into them when signing paperwork. Such practices are growing increasingly common with manufacturers including G.M., Kia, Hyundai, and Honda.

Even worse, the existence of such car data can be dangerous to victims of abusive relationships, targets of political violence, and others for whom data regarding their whereabouts poses a threat to personal safety. In other words, car data poses the same risks as data collected by our phones, computers, and other smart devices. This data can be used to power innovations, but it can also be used for gross violations of privacy that benefit those seeking profit while endangering others who have not consented to its collection.