Historic Buildings Of England Destroyed During The Blitz, And What Replaced Them

On the night of August 24/25, 1940, during the Battle of Britain, a small force of German bombers targeting the Thameshaven oil facility went off course and struck numerous buildings across the City of London. The erroneous bombing was the first attack on a British non-military target, and Bomber Command responded with raids on Berlin, Leipzig, Luena, Hannover, and Nordhausen. With the bomber taboo broken, Hitler officially lifted his ban on London area bombing on August 30, and fully mobilized his bombers — some of the best in the world.

From September 1940 until May 1941, the Luftwaffe attacked cities across the United Kingdom in what the British press dubbed the Blitz, an abbreviation of Blitzkrieg. Over 32,000 tons of bombs hit London, Portsmouth, Bristol, Birmingham, Coventry, Manchester, Belfast, Sheffield, Hull, Newcastle, and Glasgow; around two million homes were damaged or destroyed, half of them in London.

During and after the war, British authorities paid some £117 million in compensation for lost possessions and a further £1.3 billion for damaged buildings. An estimated 10 million repairs were carried out, too, although these were often functional patch-ups during the war rather than full rebuilds.

Fortunately, the great majority of Britain's landmarks were either salvaged or unscathed, but thousands of houses, offices and churches were lost to history. Here's just a handful of historic buildings that were destroyed and replaced.

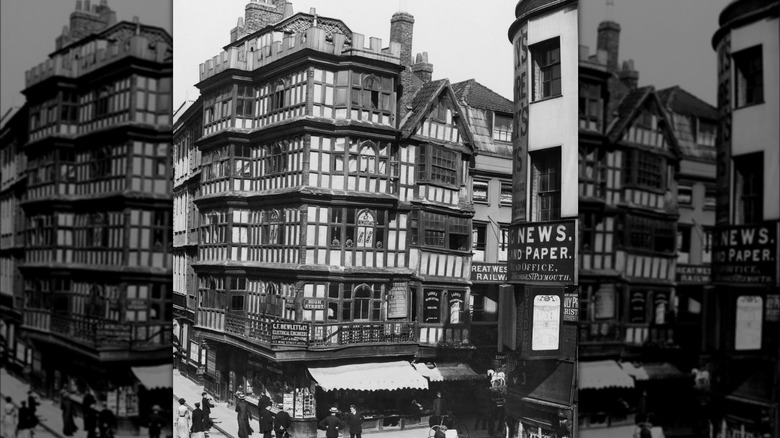

The Dutch House, Bristol

Built in 1676, the Dutch House was a landmark of Stuart architecture in the center of Bristol, South West England. The timbered five-story building hosted numerous enterprises in its 264-year history, including offices, retail businesses, and a bank.

The Luftwaffe was not the first threat to the Dutch House; in 1900, councilors planned to destroy the building to ease traffic between Broad Street and Wine Street. Fortunately, the Lord Mayor's opposition preserved the Dutch House for another 39 years, although its ground floor was reduced to expand the pavement in 1908.

The Blitz came to Bristol at about 6 pm on Sunday, November 24, 1940. Over the next six hours, 148 bombers dropped over 12,000 incendiaries and 1,540 tonnes of high explosives, causing dozens of fires, bursting the city's water mains, and striking the Dutch House, collapsing much of its interior. The beautiful eastern exterior remained, but an army demolition team pulled it down three days later. Today, the site is a paving area near a barbershop.

London Necropolis

The London Necropolis Railway was a funeral train service that carried coffins and mourners from Waterloo Station in central London to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey. One of the oldest locomotive services in the world, the London Necropolis Railway opened in 1854 and ran for 87 years until April 17, 1941, when a hail of incendiaries and high explosives hit the station.

The station's workshop, chapel, waiting room, and rolling stock were all destroyed, although the offices and platforms survived. Still, investigators declared the Necropolis was demolished and officially closed the site on May 11, 1941.

After the war, authorities decided to abandon all plans to reopen the station owing to the cost of repairs and advancements in motoring alternatives. In 1947, Southern Railway occupied the surviving railway facilities and the British Humane Association bought the office building. The terminus at 121 Westminster Bridge Rd exists today, as do numerous sections of track, one of which features a small commemoration.

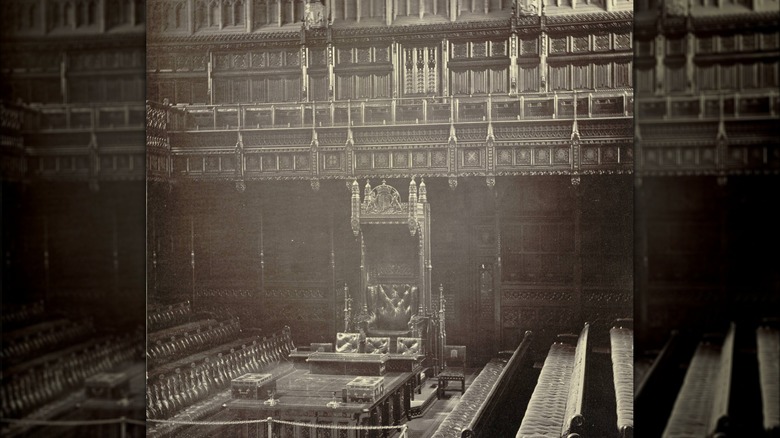

Commons Chamber, London

German forces ended the Blitz on the night of May 10/11, 1941 with the largest raid of the entire eight-month campaign. A full moon helped the Luftwaffe fly 571 sorties over the capital and drop 711 tons of high explosives and a further 86,173 incendiaries. It was a devastating attack, although the terrible innovation of war would soon produce even more powerful conventional weaponry such as the "Earthquake Bomb."

Several incendiary bombs hit the Palace of Westminster and destroyed the Commons Chamber, the center of Britain's famously raucous party debates. Volunteer fireman William Sansom recalled how the fires tore through the iconic building:

"In the morning there was nothing left of the famous House but a charred, black, smouldering, steaming ruin. The Bar no longer stood to check intruders. The Speaker's chair was lost. The green-padded leathern lines of seats were charred and drenched. The ingenious, ingenuous, most typical gothic innovations of the old period had gone forever."

After the war, the Chamber was rebuilt for £2 million, about 10% of the £20 million damage caused on the Blitz's final day.

The Great Synagogue, London

In 1690, Benjamin Levy, a founding member of London's Ashkenazi community, financed the Great Synagogue, which was built in Dukes Place in Aldgate, City of London. The institution became a center for the capital's Jews and, in 1870, formed the United Synagogue union of British Orthodox synagogues.

On May 10/11, 1941 — the last and biggest raid of the Blitz — a cascade of Luftwaffe bombs gutted the synagogue, strewing tons of rubble across the building's battered frame. Its remains were demolished in September 1941, and congregants used a temporary structure for some 15 years until its closure on October 26, 1958.

Today, all that remains of the Great Synagogue is a plaque on the corner of Dukes Place and St. James's Passage, commemorating its 251-year existence.

Holland House, London

If you see the gabled facades and tranquil moat of the youth hostel at Holland House, you could be forgiven for thinking the splendid 17th-century building was left unscathed by the Blitz. However, the hostel occupies only the east wing of what was once an enormous stately home in Kensington's Holland Park.

Sir Walter Cope built the sprawling mansion in 1605, and many historical figures coalesced there, namely Oliver Cromwell, the Parliamentarian leader of the English Civil War.

German bombs hit Holland House on September 27, 1940, destroying much of the 335-year-old landmark. It wasn't long before Jack Catchpool, national secretary of the Youth Hostels Association, visited the ruins with an eye for opportunity.

Catchpool envisioned the surviving east wing as a grand English meeting place for young people from around the world, and this was realized in 1952 when he successfully lobbied the London City Council to purchase the property. After a lengthy restoration, Queen Elizabeth opened the hostel on May 25, 1959.

Holford House, London

A few miles northeast of Holland House was Holford House on the northern tip of Regent's Park, near Macclesfield Bridge. Wine merchant James Holford commissioned the building in the early 1830s and doubled its size 10 years later, creating a grand mansion with a ballroom, a banqueting hall, and a staff of 16.

In 1874, some 20 years after Holford's death, a boat explosion on Regent's Canal shattered 2000 windows and blew a heavy door off its hinges, landing its Baptist owners — who converted the property into a college in the late 1850s — with an expensive, unsustainable bill.

By the Second World War, Holford House had long been a financial liability. Artists, cricketers and businessmen came and went but it was the famous dancer and actress Maud Allen who stayed, living in the mansion's west wing from 1910 to 1942, when Luftwaffe bombs obliterated it. Demolition followed in 1948 and today only traces of the grand old house remain.

Carlton Club, London

From 1835 to 1940, gentlemen of the Carlton Club met at 94 Pall Mall. The imposing Georgian building — which was remodeled in 1856 — served as a command center for the Conservative Party until Benjamin Disraeli established the Conservative Central Office in 1870. Despite this, the Carlton Club remained — and remains — an important component of the Conservative Party, albeit around the corner at 69 St James Street.

The Carlton Club's tenure at 94 Pall Mall ended abruptly on October 14, 1940, when a Luftwaffe bomber scored a direct hit and destroyed the 105-year-old building. No one died in the blast, causing rival Labour Party figures to quip morbidly "The devil looks after his own." Also fortunate were the club's many portrait paintings, which survived the blast and moved to the current location in 1944.

In 1963, members of the Junior Carlton Club purchased the ruined site at 94 Pall Mall and built a modern development they dubbed "the club of the future." However, members abhorred the grey mid-century style and flocked to St James Street. Today, 94 Pall Mall lives on as an office block.

St. Mary the Virgin, London

At a glance, the above photo may look like another bomb tour from the early 1940s, but it was taken in July 1964 (weeds like that don't grow overnight). The vicar Canon Mortlock received Robert Davison, Marshall Sisson, and Patrick Horsebrugh, who planned to dismantle the ruins of St Mary the Virgin church and rebuild them some 4,000 miles away in Fulton, Missouri, home of President Harry Truman.

St Mary the Virgin was built 870 years prior, around the late 11th or early 12th century, during the rule of the House of Normandy. Centuries later, in 1666, the church fell — like many buildings in the area — to the Great Fire of London. Sir Christopher Wren rebuilt the church under a royal commission from 1670 to 1677, adding a cupola in 1679.

The Renaissance-Baroque landmark endured for another 261 years until December 29, 1940, when a particularly fierce bomber raid dubbed "The Second Great Fire of London" devastated tracts of the English capital. All that remained of St. Mary the Virgin were walls, columns, and the bell tower.

Almost 30 years later, on May 7, 1969, St. Mary the Virgin reopened in the American Midwest with a ceremony attended by many American and British dignitaries, including Mary Soames, Winston Churchill's youngest daughter.

St Dunstan-in-the-East, London

Like its elder relative, St. Mary the Virgin, St. Dunstan-in-the-East endured both the Blitz and the Great Fire, which tore through the 12th-century church in September 1666. It was another project for Sir Christopher Wren, who topped St. Dunstan with a gothic steeple after some 30 years of rebuilding and refurbishments.

Little upkeep seemed to follow the builders' painstaking efforts, and by the early 19th century, St. Dunstan was in a poor state. Architect David Laing led a rebuild from 1817 to 1821, giving the institution another 119 years of religious life.

Bombs struck St. Dunstan-in-the-East on May 10, 1941 — the biggest raid of the Blitz. The tower and steeple survived but the hall was ruined and remained so for 25 years. In 1971, the City of London Corporation opened the ruins as a public garden with lawns, benches, vines and fir trees; the site is a green, medieval haven among the steel and glass of towering skyscrapers.

70,000 London homes

The Blitz damaged at least 1.7 million properties in London during its eight-month attack and completely destroyed around 70,000 structures. Historian Richard Titmuss estimated that some 29% of Britain's pre-war housing stock was affected and that roughly 1,505,000 civilians were made homeless at some point during the conflict.

Legacies of destruction are everywhere in contemporary London. If you notice an interruption in a row of 19th or early 20th-century housing, it is likely courtesy of Adolf Hitler. The SE4 postcode in south London, for example, suffered five strikes from V2 rockets, including a hit on February 2nd, 1945, that destroyed 20 houses between Finland and Revelon Road. Today, a school stands in the space cleared by the V2's one-ton warhead.

Perhaps the biggest legacy of the Blitz is the Barbican Estate, which was built on 16 hectares of bombed land throughout the 1970s and opened by Queen Elizabeth in 1982. The brutalist landmark proved divisive; the Queen described it as "one of the wonders of the modern world," while architecture Rowan Moore described it as a "monument to good design," while respondents to a 2003 architecture survey named the Barbican Centre as the ugliest building in London (via Icon).

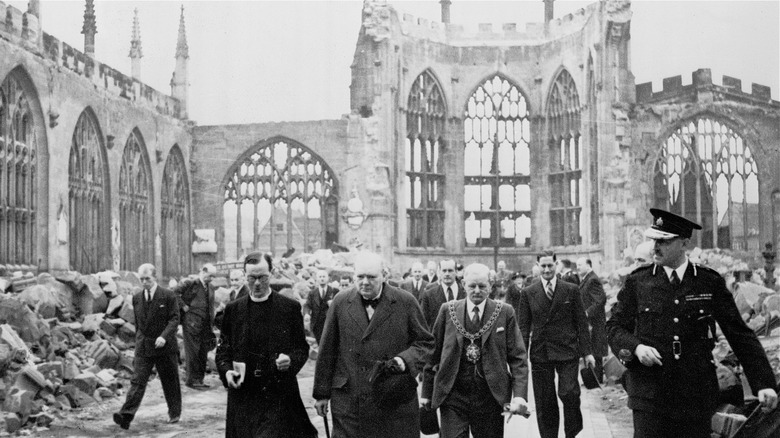

St Michael's Cathedral, Coventry

Over 40 air raids struck the midlands city of Coventry from June 25, 1940, to August 3, 1942. Two raids in April 1941 caused widespread destruction and death, but it was the attack on November 14th, 1940, that was the very worst.

The first incendiary bombs hit at 7:10 pm and continued for almost 12 hours, igniting much of the city center. Bombs hit St. Michael's Cathedral at around 7:40 pm, and fires grew until 11 pm, when Provost Howard could do nothing but watch a full inferno burn his beloved cathedral to the ground.

In total, the Luftwaffe dropped 30,000 incendiaries, 50 parachute mines, 64 light-capacity flare bombs, and up to 1,600 high explosives. The payload destroyed 4,300 homes and gutted St. Michael's 14th century frame.

Today, the cathedral's medieval shell stands by a modern structure finished in 1962. The site is perhaps the best-known memorial to the Blitz.

The Ring

Built on Blackfriars Bridge Road in the late 18th century, the Ring began life as the Surrey Chapel and it was replete with the best amenities of the day including gas lighting, underfloor heating, seats for 1,200 people, and even an organ with special thunder and lightning effects.

The chapel closed in 1881 and was repurposed numerous times throughout the remainder of Victorian London. In the early 20th century, after stints as a warehouse and a theater, the Surrey Chapel became the Ring, a boxing venue known for its aggressive spectators as much as its bloody prizefighter.

The Ring's 150-year history ended on October 25, 1940, when Luftwaffe bombs removed the roof and half the exterior wall. The remains were demolished after the war, and Orbit House, a nondescript office tower, occupied the site in the 1960s. Unlike its adaptable predecessor, Orbit House was demolished just 30 years later. Today, a similarly bland glass structure called Palestra — Greek for wrestling ring — stands on the site.