Commercial Space: What You Need To Know About The Low Earth Orbit Economy

The story of human progress has always been about the pioneers who dared to cross the river, explore the cave, or sail beyond the horizon. When those who go first return, what was dangerous and difficult becomes commonplace over time. Crossing the river is no longer a suicidal endeavor; the man who went before built a bridge. A transatlantic crossing no longer requires blind faith in eventual landfall; there is now a route. The story of exploration is the story of humanity.

In May 1607, a small flotilla of three English ships landed along the coast of North America in what would become Jamestown, Virginia. The pioneers and half-mad explorers had come and gone. Columbus landed in Hispaniola on his fantastical all-or-nothing trip in 1492. Explorer Amerigo Vespucci scouted the coast between 1497 and 1504, lending his name to the enormous landmass heretofore unknown to Europe. Navigators had scouted the shoreline, noting river inlets and potential landing places. The barrier to reaching the New World was still high, the risk enormous, the potential limitless. But something had changed: those who risked everything to go before had made it possible for private enterprises to follow.

No longer were such expeditions solely a function of government. The privately owned Virginia Company that launched the expedition did not seek knowledge but profit. It is often the way of exploration. The half-mad or absurdly courageous go first, followed by opportunists and capitalists. Markets open, technologies rise, and what was once nigh-on impossible becomes commonplace over time.

We are in a new age of exploration, profit, cooperation, and conflict, no less stupendous than any in history. This time, it will not take place on the shores of an unexplored continent but on the fringes of a vastly more unknown and less hospitable environment: space itself.

Broaching the final frontier

The opening of Star Trek said it pretty well. Unless physicists discover some route to the multi-verse, space is the final frontier. And it is no less mysterious and perhaps significantly more dangerous than the unexplored shores of the Americas. It took humanity about 200,000 years to circumnavigate the planet for the first time. In the five centuries since we have mapped nearly every inch of the globe, explored some of its depths, and departed its surface.

From the onset of the Jet Age, the journey from the first flight to putting a man on the moon took a stunningly short 66 years. Similar to the earliest voyages during the Age of Discovery, it took enormous governmental investment, brilliant planning, and impossible courage to advance from a puttering flight over North Carolina to boots on the surface of Earth's satellite.

The story of the Apollo program is often wrapped up in the ethos of the Cold War. Sometimes, it seems that the return of Apollo 17, the final lunar mission, in December 1972 put a period on space exploration. The Americans beat the Soviets to the moon. A handful of lunar missions followed, and humanity moved on —except it didn't. Though space exploration never got the monumental coverage it had in the run-up to the moon landing, NASA and other national space agencies continued their mission.

After the moonshot

With the incredible accomplishment of the moon landing, NASA turned its eye toward making the trip to space and back safe and reliable. Like crossing the Atlantic in the centuries following Columbus, the risks and costs remained considerable.

NASA launched 32 Space Transportation System (STS) flights to low Earth orbit and back. Each flight contributed to a growing list of first-time accomplishments. STS-2 marked the first re-use of a spacecraft. Sally Ride became the first American woman in space. Engineers installed a cargo bay in the shuttle, and the first goods were transported into space. Crews captured and repaired satellites, prolonging their utility. We learned the impact space travel has on the human body.

Like all pioneering ventures, the shuttle program brushed against tragedy. The Challenger infamously exploded on launch in January of 1986. In 2003, Columbia disintegrated while attempting to land. To date, 23 explorers, both Soviet and American, have died in the pursuit of delving into space.

In the meantime, inventions used for space exploration quietly revolutionized life on Earth. Global positioning satellites guide us to destinations, air purifiers improve the air quality in our homes, freeze-drying preserves foodstuffs, and phones capture moments with photographic technology developed for space. The lessons learned from exploring low-orbit during the latter half of the 20th century have created industries and economies on Earth and opened the door for commercial exploration.

Commercial space

In the same way the Virginia Company's expedition built on government investment in exploration, space travel is poised to open up commercially. The first European explorers crossed the Atlantic with the entire government's financial and political support. But, as our Virginia Company example shows, the gains made by the pioneers eventually made that same exploration possible for private concerns.

The concept of commercial space may be stunning to those who grew up in space exploration's infancy. The dedication, sacrifice, immense danger, and vast amounts of treasure it takes to send a human into space make it commercially infeasible. However, with each passing year, near-earth space exploration becomes safer and less expensive, introducing the possibility that for-profit organizations, like the Virginia Company, may soon launch capitalist missions into orbit.

Similar to how markets ultimately blossomed on the shores of the Americas during the colonial era, inner space, so to speak, is primed for the development of a low Earth orbit economy. In the case of the colonization of North America, colonies ultimately began to send raw materials, some previously undiscovered, back to their mother nation. These materials contributed to the economic health of the mother nation, which re-invested in exploration, which unfolded in myriad ways.

Technologies that aid deep-space exploration continue to develop, and NASA has its eye on advancing beyond the realm of near-space. But they have already begun to make the hand-off of low Earth orbit to private business.

NASA and commercial space: the companies working to make space accessible

The shuttle program's death sowed the seed that would blossom into a partnership between NASA and private companies. By 2005, the death of the shuttle was imminent, and NASA needed a solution. They began an initiative to select private companies to build and operate spacecraft to supply the space station. NASA would contract private concerns to take up some of the responsibilities previously exclusively held by the national space organizations. The space agency would share its technical knowledge and define the mission, leaving private enterprises to determine best how to accomplish it.

The Collaborations for Commercial Space Capabilities (CCSC) emerged in 2014. It is just one of several initiatives by NASA to develop relationships with private companies to develop new capabilities for governmental and commercial use. In June 2023, NASA announced CCSC-2. A team of seven companies was selected to develop the low Earth orbit economy. Blue Origin, Special Aerospace Services, Space X, Northrop Grumman, ThinkOrbital Inc., Vast Space LLC, and Sierra Space Corporation are part of a mission to increase human presence in low Earth orbit (LEO).

These companies are major players in the burgeoning LEO economy but hardly tell the entire tale. NASA contractors like Lockheed Martin, Aerojet Rocketdyne, Boeing, Collins Aerospace, and many others contribute to the mission in various ways. The industry partners for the Artemis program alone have nearly 4,000 suppliers covering 49 states. Birthing an economy in space means bolstering the one on Earth first.

What is the low Earth orbit economy?

Low Earth orbit (LEO) constitutes the orbital space less than 1,200 miles (2,000 km) into the atmosphere. The International Space Station and over 90% of satellites operate in this zone. This section of space is relatively convenient for transportation, resupply, and communication.

NASA's private partnerships aim to develop a network of producers of goods and services that can reach, navigate, and eventually live in LEO. The barriers to entry are still high; space exploration is wildly expensive, and, for now, the rewards are relatively insignificant. You won't see a local coffee vendor setting up shop just off exit 15 of the galactic superhighway anytime soon. But companies competing to produce cheaper and more effective products for the low Earth orbit economy will empire the LEO economy. Just see the work Rocket Lab and others have done in pioneering reusable rockets.

While the LEO economy is currently relegated primarily to Earth in terms of development and production, the ultimate goal is to increase the number of humans in space while generating an economy that is literally in a low Earth orbit. The current NASA Code of Conduct for the International Space Station Crew allows members to engage in limited commercial activity. Extrapolate forward to a fully-populated LEO replete with science labs, training facilities, and even vacation resorts, and what you have is the potential for enormous economic activity not only in traveling to LEO and back safely but in sustaining life there.

Artemis and the Lunar Gateway

What's in it for NASA? By applying free-market competition, the private LEO economy frees up resources for NASA to take on deep space exploration. Low Earth orbit is just the beginning. With private companies taking up the responsibility for further development in Earth's near neighborhood, NASA can focus on deep-space exploration. The eventual objective is Mars, but humanity will require stepping stones to get there.

The Lunar Gateway project aims to place a space station in lunar orbit. Similar to the ISS, the Gateway will be a floating laboratory and testing environment to better prepare humans for potential missions to Mars. The first two modules — the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) — are slated to launch in 2025. These modules will fly aboard SpaceX's Heavy Falcon rocket, which was developed by a private concern.

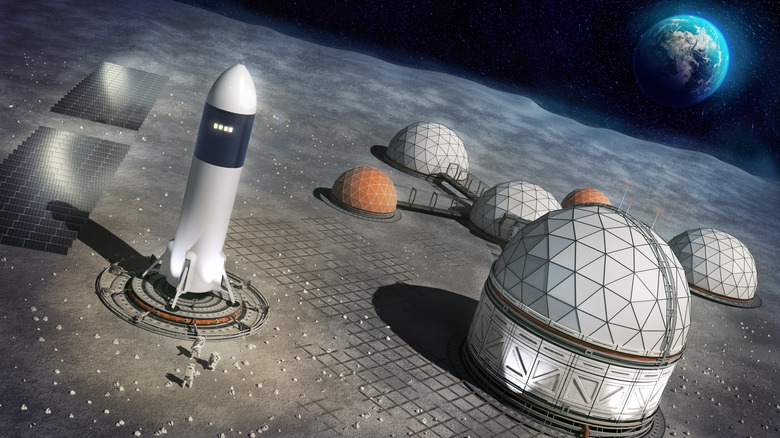

The Gateway is just one part of a larger ambition to place a permanent facility on the surface of the Moon itself. The first Artemis mission, an uncrewed 25-day mission launched in November of 2022, laid the groundwork. Artemis II will launch a four-astronaut crew on a 10-day lunar flyby sometime after September 2025. Artemis III, post-September 2026, will land the first humans on the moon's surface since Apollo 17 in December 1972. Artemis IV will send a crew to initiate habitation aboard the Gateway lunar station. The age of the moon base, sci-fi fodder since the beginning of the jet age, is upon us.

Space tourism

The first tourist in space blasted out of the atmosphere in April 2001. Dennis Tito, an American businessman and aerospace engineer, paid $20 million to join a Soyuz supply mission to the International Space Station. Controversial and incredibly expensive, the Tito trip will likely prove to be just the first of many space missions blasting off for recreational purposes.

Fast-forward two decades, and the idea of launching a trip into space has become far more accessible. Jeff Bezos's Blue Orbit — one of NASA's partners in developing the LEO economy — is taking bookings for future space flights to his space station. Virgin Galactic is in the same boat. Seats are set to cost between $250,000 and $500,000 – hardly cheap enough to take the kids up on a weekend trip, but a lot more reasonable than Tito's 2001 flight. Space X sent an all-civilian flight into space in September 2021. Those a little more cash-strapped or averse to blasting off in a rocket can book a $50,000 ballon ride to 100,000 feet on a six to 12-hour round-trip from another company looking to cash-in on the new frontier.

The phrase space tourism conjures images of children pattering around a hotel pool while their parents sip mai-tais with the infinite void of the cosmos overhead. The idea still seems absurd, but no more than grilling a burger and taking a dip at the Jamestown Beach Event Park might seem to an English peasant in 1607.

Nationalism in space

A student of history might point out that mercantilism, colonization, and the discovery of "new" territory have also put a terrible strain on human interaction. The European appropriation of the Americas alone caused millions of deaths and sparked dozens of major conflicts. Can we expect space exploration to be any different? Or will Space Force Guardians be gearing up for battle?

According to World Population Review, more than 70 space agencies exist worldwide, with more than a dozen more in development. As of 2022, only 16 are capable of executing a space launch. High military spending and technological development are characteristics of nations capable of hitting orbit. However, the LEO economy will certainly increase this number as space travel costs decrease and its feasibility improves.

Though it's impossible to predict what will happen in the future, diplomats and statesmen are already working on ways to divide the space pie fairly. The 2020 Artemis Accords, signed by more than 40 countries, aim to promote safe and equitable coexistence between the increasing number of nations capable of space travel.

Future of the LEO economy, near and far

There is little doubt that the LEO economy will grow in the coming years. Competition amongst private actors and continued innovation and development by governmental agencies will combine to create opportunities undreamed of a mere decade ago. Space travel is an emerging market expected to be worth up to $3 trillion in the not-too-distant future. Over 100,000 commercial spacecraft are expected to be in existence by 2030, per Princeton University's Journal of Public and International Affairs.

Like outer space itself, the benefits of the low Earth orbit economy might well be so vast as to be infinite. There is no telling what advances the development of this emerging market will bring to life on Earth and further forays into deep space. Space travel is emerging from the exclusive arena of governmental agencies and adding the power of a competitive market to innovate and develop commercial use.

It is a fun mental exercise to envision the boons, discoveries, heartache, and conflict that may emerge from developing the low Earth orbit economy. But as tempting as it is, only the flow of time will reveal the course of human exploration of outer space. Could the members of the Virginia Company have imagined the treasure and blood spilled in the pursuit of exploration of the Americas? There's no crystal ball that can foresee what space holds in store for humanity, but it would be fair to say we are on the cusp of another great Age of Exploration.