Six Scientific Achievements Once Thought To Be Impossible

History is full of naysayers. For every out-of-the-box thinker who wondered if something might be possible, there were a hundred voices to shout them down. Imagine the wonder of someone transplanted from a mere 300 years ago to the present day. Daily life would be virtually unrecognizable.

The miracles modern humans take for granted every day: instant light in the dark, trans-oceanic travel in hours, transmitting voices through the air, let alone the masses of information broadcast by Wi-Fi. These things would be inconceivable to Benjamin Franklin, let alone Julius Caesar. Considering humanity has trod the earth for nearly 200,000 years, the last few hundred have been unprecedented in technological advancement. What is commonplace to us is beyond the wildest imaginings of yesteryear.

The inventors of these technologies have not always had an easy road. Pioneers and dreamers are often met with the sneer of impossibility from those who lack the imagination to see something a new way. Fortunately, the scope of human curiosity trumps that of skepticism, and we can enjoy the fruits of thinkers who cast aside the pessimistic and forged into new realms. Join us as we examine seven scientific achievements that were once thought to be impossible fantasies.

Heavier-than-air flight

Earthbound for most of history, we once thought we were destined to stay on the ground. After all, how could something heavier than air leap into the sky and fly about like a bird? Other than birds, of course. The idea of a contraption that could defy the laws of gravity was so absurd that in 1903, the New York Times claimed such an invention would take "from one million to ten million years — provided we can eliminate ... the existing relation between weight and strength in inorganic materials."

On September 19, 1783, a pair of French brothers named Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier stitched a cotton canvas and paper balloon together, tethered it to the ground, and lit a fire beneath it, watching as it rose into the air. They repeated the feat a week later in front of King Louis XVI, attracting the attention of the Académie Royale des Sciences. After further experimenting, Pilâtre de Rozier, a physician, and François Laurent, the Marquis d'Arlandes, agreed to climb into a basket attached to the balloon. They were the first humans to take to the sky.

A skeptic might claim that lighter-than-air flight is a matter of natural law, but heavier-than-air flight violates the laws of physics. That skeptic would need to consider the concept of lift and the invention of the internal combustion engine. A mere nine weeks after the New York Times claim, the Wright brothers, bicycle mechanics from Ohio, took to the sky at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, forever changing the course of human history.

Splitting the atom

Some ancient thinkers claimed that four essential elements — earth, water, air, and fire — made up all things. Greek philosopher Democritus argued that these four elements were not the basic building blocks of matter, preferring his theory that all things originate from tiny particles. In the early 1800s, British chemist John Dalton discovered that Democritus was right — all things are made up of tiny particles called atoms.

In the 1930s, scientists began using particle accelerators in hopes of splitting one of these atoms. The world's great geniuses, including Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and Ernest Rutherford, believed that tapping into atomic power was nearly impossible. But the desperate geo-political situation surrounding World War II drove funding into inventing wonder weapons that might win the war, and after years of research and experimentation by some of the greatest physicists to ever live, the American Manhattan Project did the "nearly impossible."

Humanity had never attempted to instigate such a release of energy as they were planning for July 16, 1945. The outcome of the United States' first nuclear blast, the "Trinity" test, was far from certain. Physicist Enrico Fermi took facetious bets on whether the detonation would destroy the earth. The chance of the entire atmosphere lighting on fire before spreading to ignite the hydrogen in the ocean, thus destroying the planet, was not outside the realm of possibility.

The atomic bomb did not destroy all of humanity, though nuclear weapons have given us the ability to do so.

Breaking the sound barrier

Game-changing rockets and jet engines developed during WWII pushed aviation into a new realm. Jets could soar higher and faster than their piston-powered predecessors, which begged the question: Could an aircraft break the speed of sound?

The concept of the speed of sound was not new. As far back as the 17th century, European scientists had identified and refined exactly how fast sound traveled. French scientist Pierre Gassendi took the first stab at it by observing the flash of a gunshot at a distance and measuring how long it took for the report — the firing sound — to arrive. He overestimated it as about 478 meters per second, but the concept was born. By the early 1940s, scientists knew it was closer to 331 meters per second. The question now was whether a human-piloted aircraft could exceed it.

When an object travels through the air, it compresses the air in front. The concern with sending an aircraft at those speeds was that the compressed air would destroy the vehicle via an invisible barrier. As Chuck Yeager taught us on October 14, 1947 in his bullet-shaped Bell X-1 experimental aircraft, though, the product of supersonic flight is not destruction but a sonic boom. Sonic booms are formed by pressure waves traveling down the fuselage, like a ship's wake, dropping booming sounds along its flight path.

Marconi's radio

The very basics of radio communication sound like something from a ghost story: Voices traveling across time and space without so much as a telegraph wire to push them along. Radio communication may have fallen by the wayside with the advent of satellites and fiber optics, but the miracle invention of Guglielmo Marconi presented the 20th century with a communications revolution.

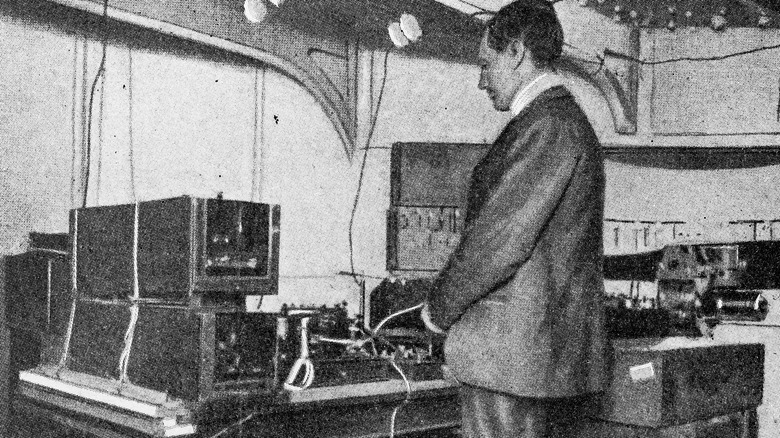

Like most inventors and discoverers, Marconi used the knowledge of pioneers before him to develop radio communication. Notably, German physicist Heinrich Hertz showed that electromagnetic radio waves could be transmitted and detected over short distances. Marconi was not the only tinkerer on the path to introducing radio communication, either — at least four companies were working to be the first, and Nikola Tesla was reportedly on the trail of cracking the same nut.

Guglielmo Marconi was a celebrated inventor and giant of the 20th century. The foundation of his reputation stems from his experiments at his father's estate in England. In 1895, Marconi experimented until he finally sent a wireless signal over a half-mile. The initial communication of this new miracle technology relied on Morse code, which was developed for telegraphy. But further experimenting allowed humanity's voice to reach around the globe in a way that would have seemed like pure magic only a few decades prior.

Edison's lightbulb

We have relied on fireplaces and warm hearths to heat our meeting spaces. Torches, then candles, perhaps later gas-fueled wall sconces to chase away the dark after the sun goes down. The ancients would be amazed to have a clean, cheap, instant source of light in any room at the flick of a switch, which is why the light bulb may be one of the most underappreciated inventions of the past century.

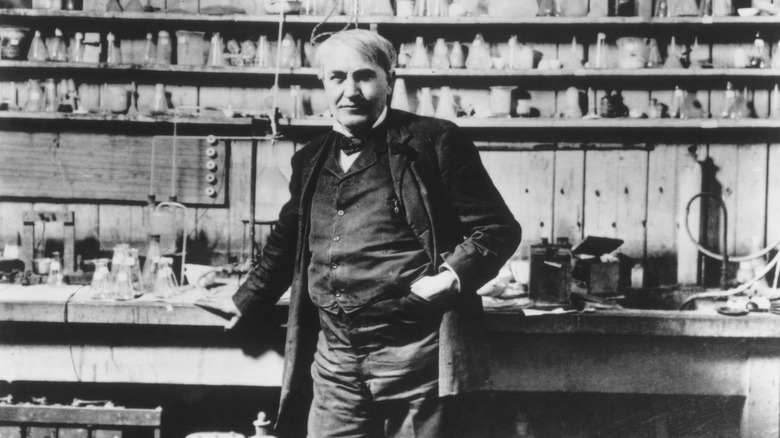

Thomas Edison was already a well-known inventor when he turned his attention to the light bulb. By the end of his life, he held over 1,000 patents. The thing is, Edison did not invent the lightbulb — scientists had been tinkering with incandescent lighting since at least 1835. In the decades between then and Edison's patent in 1879, hundreds of people experimented with the devices. Different filaments and combinations of inert gases or vacuum-sealed glass helped prevent the fragile bulbs from burning out too quickly.

Thomas Edison set his assistants at Menlo Park to discover the best conditions for long-lasting light. Carbon-arc lamps were already used as street lighting, but if he could develop a superior source of indoor lighting, he could change how people lived. Ultimately, Edison settled on copper wire through a lamp with a relatively low current. He also developed the screwing base for light bulbs we use today in the process. And that's not all — one of Thomas Edison's companies, General Electric, continues to dominate, building some of the products he created.

Flying the Atlantic

The radio allowed information to fly worldwide, and human beings weren't far behind. The Wright Brothers' flight in 1903 was momentous, but Charles Lindbergh's flight across the Atlantic Ocean illustrated that aviation would not remain a fringe community for daredevils. Indeed, Lindbergh changed flight forever by proving the New and Old World were not as far apart as they once were by making the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight.

In hopes of beating competing teams to a $25,000 prize for the first solo pilot to make a nonstop flight from New York to Paris, Lindbergh gathered sponsors and commissioned a custom aircraft. The result was the Spirit of St. Louis, a single-engined monoplane with a 223 horsepower Wright J-5C engine. Its fuel tanks took up so much space that the young pilot had to use a periscope for a forward view. Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, New York on the morning of May 20, 1927. After a 33.5-hour flight, he set down to the cheers of over 100,000 French citizens who greeted him at Le Bourguet Field near Paris after an exhausting flight of over 3,600 miles.

Today, thousands of people make once-unthinkable flights over the widest oceans and tallest mountain ranges because of aviation pioneers who did it the hard way first.