The Shady Side Of Microsoft

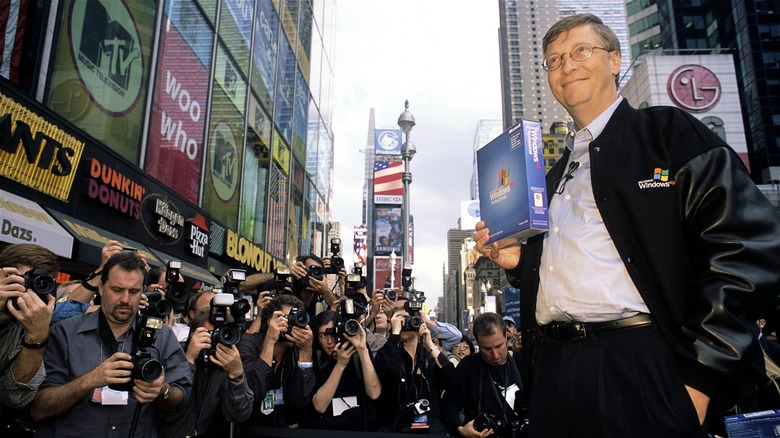

Microsoft is one of the most important companies of the 20th century. Within two decades of its founding, Bill Gates and Paul Allen's software project had turned into a technology behemoth, revolutionizing both the workplace and the home office.

Gates and Allen became very wealthy men, especially Gates, who has been among the richest people in the world since the late 1980s. In 2000, Gates and his wife Melinda established the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a private $77.6 billion fund committed to international development. Since its founding, the organization has increased vaccination, decreased child mortality, cut poverty, and saved over 122 million lives.

However, few fortunes are made without tough decisions and dubious practices. Microsoft has been accused of tax avoidance, privacy issues, and monopolistic intentions. Stories of anger and abuse have emerged, too, and so have allegations of censorship, unfair contracts, and even war profiteering. Here is the shady side of Microsoft.

Bill Gates and Paul Allen's relationship

Bill Gates and Paul Allen met at Lakeside School in Seattle. Allen was almost three years older than Gates, but they shared an intense interest in software and computing. The pair worked on numerous projects together, including a computerized traffic tape system called Traf-O-Data.

Later, after dropping out of Washington State University, Allen convinced Gates to leave Harvard and move to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they established Microsoft on April 4, 1975. Four years later, Microsoft returned to the Seattle area, settling in Bellevue, Washington.

As Microsoft expanded in the early 1980s, disagreements about staff and product strategy frayed Gates and Allen's relationship. Then, sometime after a cancer diagnosis, Allen overheard Gates speaking with Steve Ballmer, complaining about his old friend's lack of productivity. "They were talking about how they were planning to dilute my share down to almost nothing," Allen told 60 Minutes, "It was a shocking and disheartening moment for me ... I was still in the middle of radiation therapy."

Ballmer visited Allen's home and apologized. Gates did not, although he did send him a six-page letter, apologizing for the discussion and recognizing Allen's value to the company. Allen left the company shortly thereafter, taking a third of Microsoft's shares with him.

Allen and Gates reconciled, despite Paul Allen going public with these accusations and others in interviews and his memoir "Idea Man." Allen attended Gates' wedding in 1994 and, after his second bout of cancer in 2009, Allen described Gates as "everything you'd want from a friend."

Monopoly lawsuits

On May 26, 1995, Bill Gates sent an email to staff titled the "Internet Tidal Wave." In it, Gates stated his intention for Microsoft to "go overboard on internet features." By the end of the year, the company released Internet Explorer, its first internet browser. Then, in 1996, Microsoft provided the software free of charge as part of the Windows 95 operating system bundle. This massively undercut competitors such as Netscape Navigator, which charged users $49 to install the program on their operating system.

Microsoft's gambit boosted its share of the browser market to 10%, but critics alleged that the tech giant had made it purposefully difficult to install any other browser on Windows systems. The Department of Justice looked into the claim, and on May 18, 1998, the federal government filed an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft, accusing it of quashing competitors with monopolistic, obfuscatory practices.

In late August 1998, Gates attended a 12-hour deposition in which he evaded questions and exuded general contempt for his interviewers. Early in the trial, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson showed a recording of the deposition and said, "Microsoft, you lost me on day one."

Ultimately, the judge ruled Microsoft had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. Jackson ordered Microsoft to split itself into an operating systems business and an applications business. However, after a lengthy appeal, the government reversed its decision to seek a breakup, opting instead for a deal in which Microsft would be more cooperative with third-party software and allow three investigators to monitor compliance for five years. The company avoided the worst consequences, but this was still one of Microsoft's biggest mistakes.

Accusations of war profiteering

Microsoft unveiled the HoloLens virtual reality headset in 2015, stirring interest with its interactive multimedia capabilities. Three years later, in November 2018, the tech firm won a $480 million contract to provide HoloLens headsets to the U.S. Army, which stated that the headsets would "increase lethality by enhancing the ability to detect, decide and engage before the enemy." Microsoft announced the deal more euphemistically, explaining how the technology would "provide troops with more and better information to make decisions."

By February, a group of Microsoft workers circulated a petition headlined "HoloLens For Good, Not War." In it, the workers expressed their refusal to "create technology for warfare and oppression" and demanded that Microsoft cancel the headset contract. The workers also criticized the company for not adequately informing employees about how their work would be used.

Days later, at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, CEO Satya Nadella defended the contract to CNN Business, "We made a principled decision that we're not going to withhold technology from institutions that we have elected in democracies to protect the freedoms we enjoy."

Tax avoidance

There have been numerous reports of Microsoft's tax avoidance, especially regarding its practice of sending U.S. profits to tax havens in Ireland, Singapore, and Puerto Rico.

During the 1990s, Microsoft saved $200 billion in taxes by outsourcing its CD software burning operations to a factory in Humacao, Puerto Rico. Microsoft turbocharged this deal in the early 2010s, employing KPMG executives to negotiate a near 0% tax rate with the island's government. Soon, Microsoft had moved some $39 billion to the Caribbean tax haven.

The IRS got wind of the deal and assembled a team of specialists led by Samuel Maruca, who launched a thorough investigation into Microsoft's labyrinthine tax structure, unearthing documents that showed underreported revenues and cynical references to the company's "pure tax play."

The agency's momentum prompted an aggressive response from the tech giant, which used every lever it could to control the situation, causing a protracted series of audits and investigations. In October 2023, the IRS claimed Microsoft owed $28.9 billion in back taxes, plus penalties and interest.

Before that, in 2021, scrutiny mounted on Microsoft's Irish outpost, which is located in Dublin but tax-domiciled in Bermuda. Media reports questioned how the subsidiary had registered $315 billion in profits despite having no employees beyond three U.S.-based directors. A Microsoft representative said, "Microsoft has been operating and investing in Ireland for over 35 years and is a longtime taxpayer, employer, and contributor to the economy."

Bill Gates' angry temperament

Casual observers may view Bill Gates as an introverted computer geek, but that would be wrong. Gates was a wilful CEO with huge ambition, high expectations, and a sharp tongue. Paul Allen said that Gates' management often consisted of "brow-beating and personal verbal attacks," adding that one had to "fight back intensely to stand your ground to make your position and your convictions expressed."

If Gates didn't like something, he'd say "That's the stupidest f***ing idea I've ever heard." He said it so often, in fact, that it became something of an unofficial catchphrase. Employees couldn't catch a break, either. Gates would email software engineers in the middle of the night with messages such as "this is the stupidest piece of code ever written."

Gates' profanity got so bad that some staff members would attend meetings just to count how many times he said the F-word. However, as unpleasant as Gates' temper may have been, his hard-driving style wasn't all bad. "You always knew what Bill thought about what you were doing," said Scott McGregor, who joined the software industry in 1978. "The goal, the motivational force for a lot of programmers, was to get Bill to like their product."

Chinese censorship

Microsoft has been criticized for its complicity in the Chinese Communist Party's censorship regime, with its search engine Bing receiving particular scrutiny. When Microsoft launched Bing in China on June 1, 2009, the organization had to adopt the country's censorious practices, which had troubled competitors such as Google and Yahoo, who subsequently ended service in the territory.

Bill Gates, however, dismissed the issue of Chinese censorship, describing the CCP's control of the internet as "very limited." Bing would go on to censor words and phrases such as "democracy," "human rights," "CCP corruption," " Nobel Peace Prize," "Chinese censorship," and "Dalai Lama."

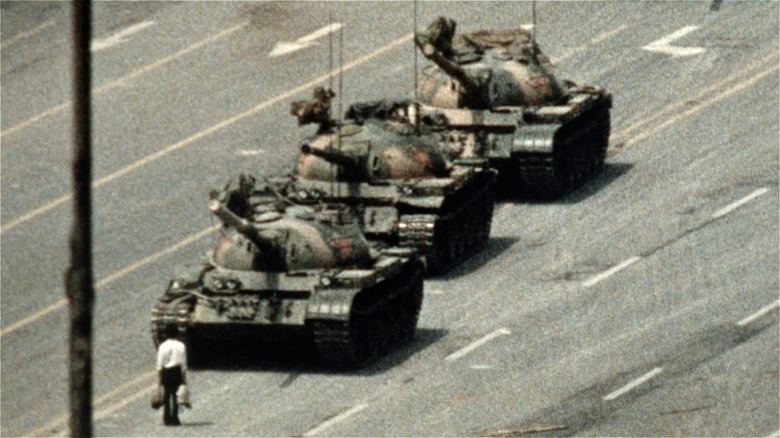

Bing also censors all references to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest, a pro-democracy event that ended in the massacre of hundreds, if not thousands of protestors. The most enduring document of the massacre is the famous "tank man" image, which captured a lone protester standing in front of a column of Type 59 tanks. Bing does not show this image in China, and in the spring of 2021, it didn't show it anywhere else in the world either. A Microsoft representative blamed "accidental human error," which means, according to experts, that Bing erroneously applied its Chinese blacklist software on a global scale.

Journalist watchlists

In the 1980s, Microsoft kept a list of journalists and classified them as "okay," "sketchy," or "needs work." The list went public during the Comes v. Microsoft lawsuit, in which plaintiffs from Iowa alleged that Microsoft overcharged them and used anti-competitive practices.

PC Magazine writer John C. Dvorak was among the blacklisted journalists because he was viewed as "uncooperative." Dvorak kept his job, but Microsoft did not provide him with information about certain Windows products, and the firm's complaints caused him to lose a column at PC Magazine Italy.

Microsoft also blacklisted tech blogger Mary Jo Foley, who wrote a story exposing that it knowingly released Windows 2000 with some 63,000 bugs in the software. "Certain Windows execs refused to speak to me or meet with me for ages because of that story," Foley told Windows-Now, "I believed, and still believe, that I was just doing my job as a reporter."

Permatemp and work culture

Microsoft has been accused of abusing permatemp contracts and demanding overly long working hours. In 1992, a group of temporary employees and independent contractors filed a lawsuit — Vizcaino v. Microsoft — claiming that because they shared the responsibilities of permanent employees, they were entitled to the same benefits, such as health insurance and company stocks.

The case was dismissed in 1994, but appeals in 1996 and 1997 ruled that the claimants were entitled to a share of Microsoft's stock purchase plan. A $97 million award was announced in 2000 and approved on April 16, 2001. An average sum of $10,000 was awarded to up to 12,000 temporary workers.

"This is a huge victory for the workers,” said Larry Spokoiny, who was hired as a software tester in a temporary capacity. ”Before, they used to do this just to save some cash for themselves. It sounds to me as if they learned something from this lawsuit, and I think many other companies across the nation are going to sit up and take note.”

Privacy and security issues

Numerous figures have criticized Microsoft for its security practices. In July 2023, Senator Ron Wyden wrote a letter to several government agencies asking for an investigation into Microsoft's negligent cybersecurity practices and their effects on Russian and Chinese hacking campaigns.

Wyden discussed Microsoft's "poor" use of encryption keys and criticized its response to the scandal, which urged customers to remove data from their own servers and move to Microsoft's cloud service. Wyden saw this as a cynical promotion, noting that Microsoft's cloud security revenues surged to over $20 billion annually following the controversy. Tenable CEO Amit Yoran took an even harsher view, issuing a broadside of criticism that described Microsoft as "grossly irresponsible," "blatantly negligent," and guilty of "toxic obfuscation."

Years before that, in 2013, it emerged that Microsoft was the first of nine tech companies to be part of the National Security Agency's Prism program, which granted direct access to users' information such as email, instant messaging, video calls, photos, file transfers, and social networking details. A Microsoft representative said, "When we upgrade or update products, we aren't absolved from the need to comply with existing or future lawful demands."

Xerox thieves?

The Xerox Alto may not have impressed Xerox executives, but its innovative graphical user interface (GUI) was a revelation for both Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, who said in a TV interview, "Within 10 minutes, it was obvious to me that all computers would work like this someday."

This was in 1979, when Microsoft worked with Apple as a third-party software developer. With the Alto in mind, Apple had Microsoft sign an agreement that stated Microsoft could not release mouse-based software until 1983, a year after the upcoming Apple Lisa system. However, Apple's project was delayed, and the contract date remained.

In November 1983, Microsoft unveiled the Windows operating system, which featured the company's first graphical user interface. Later, an indignant Jobs confronted Gates — Walter Isaacson's biography of Steve Jobs recounts the exchange. "You're ripping us off!" Jobs shouted, "I trusted you and now you're stealing from us!" Gates replied, "It's more like we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it."

Decades later, during a Reddit AMA, a user asked Bill Gates if he had copied Steve Jobs. "The main "copying" that went on relative to Steve and me is that we both benefited from Xerox," Gates said. "We didn't violate any IP rights Xerox had, but their work showed the way that led to the Mac and Windows."