Ford's Flivver: The Airplane That Tried To Make Flying Affordable

Flight has never been the sole domain of major air carriers; with sufficient training, anyone can become a pilot, and as long as you have space and licensure for it, anyone can own and operate a personal airplane. Well, anyone in the literal sense, but it's more like "anyone with $8,000 to $300,000 burning a hole in their pocket." Sadly, the cost of owning a private airplane isn't exactly something that just anyone can afford.

Back in the 1920s, though, one man had an idea to make personal flight affordable enough that just about anyone could get a plane if they wanted it. That idea was the Flivver, and that man was none other than one of history's greatest modern engineers, Henry Ford. It was Ford's hope that this experimental plane would do for air travel what the Model T did for automobiles, but unfortunately, that dream never materialized, and for a rather tragic reason.

Ford's Flivver was the average Joe's plane

The Ford Flivver, named after a slang term for the Model T, was conceptualized as a compact personal airplane. It was just big enough to fit a pilot but small enough to fit realistically inside the average garage. In fact, to work toward this notion, Henry Ford actually had the original designer of the Flivver, Otto Koppen, take measurements of his personal office just to ensure that the plane would be small enough to fit within its confines.

The plane was primarily made of wood and steel, utilizing the former for the wings and fuselage and the latter for the empennage and landing gear. The original Flivver prototype featured a 3-cylinder 35 hp Anzani air-cooled engine, though, in subsequent prototypes, this was swapped out for a 2-cylinder Ford engine, which could manage a top speed of around 85 mph.

The Flivver was first publicly unveiled on Henry Ford's 63rd birthday in July of 1926, and excitement steadily began to build over the future of personal air travel.

The tragic test flight

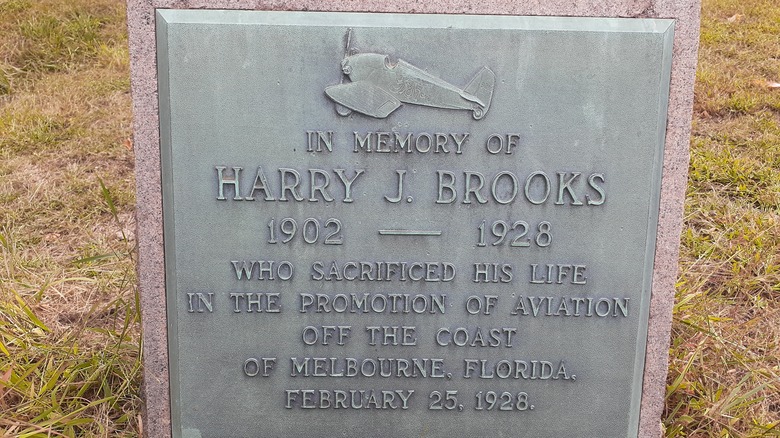

The test flights for the Flivver were carried out by Harry Brooks, the top test pilot for the Ford brand and a close friend of Henry Ford. The initial test flights of the first couple of prototypes were promising, with Brooks regularly making use of the compact vehicle to quickly travel back and forth between his home and the Ford laboratories.

In 1928, Brooks was looking to really establish the Flivver's capabilities by using it to break the light aircraft travel record by flying nonstop from Detroit, Michigan, to Miami, Florida. The first attempt at this endeavor occurred in January of that year, though it had to be cut short due to icy conditions. Brooks tried again in February and successfully broke the record by making it all the way to Titusville, Florida, though he insisted upon finishing the voyage to Miami.

Tragically, this would be the last time Brooks was seen. Those waiting for him in Miami grew worried when he was several hours late, and the next day, passing seaplanes spotted the wreckage of the Flivver in the Atlantic Ocean. Brooks's body was never recovered, and he was declared deceased when his wallet was found washed up on the beach weeks later. Engineers who inspected the wreckage determined that the rudder wire had snapped, disabling Brooks's ability to steer the plane.

The end of the Flivver

Henry Ford was devastated by the loss of his friend and immediately halted any further development on the Flivver. In a statement obtained by Smithsonian Magazine, Harold Hicks, chief airplane engineer for Ford at the time, recalled Ford's despondent state in the days following the crash.

According to Hicks, after Brooks' death, he asked Ford whether the company and Ford engineers should continue to develop the company's two-cylinder airplane engine for the Flivver. A melancholy Ford would question Hicks, asking, "What are they good for?" in regards to the ill-fated plane. Ultimately, the unfortunate crash would mark the end of its development.

One of the first prototypes for the Flivver was placed on display at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan, where it remains to this day. While Ford would continue work on commercial and military aircraft into the 1930s, this was the last time the brand experimented with personal flight.