5 Of The Coolest Images Taken By The James Webb Space Telescope (So Far)

Initially launching in 2021 after a series of delays kept pushing the window back, before eventually settling into its intended orbit around the sun in January, 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope has had many lofty expectations placed upon it. Since then the Hubble successor has taken quite a few photographs, most of which are detailed and intricate enough (due to various additional instruments) to give scientists a clearer look at — and possible clearer understanding of — what goes on in the wider universe.

A lot of those photos are also just really cool to see. Sometimes it's because they look neat, or because of the meaning and science behind them, but usually it's a combination of both. From celestial bodies to abstract interstellar clouds, the Webb's photo library is a wealth of cosmic rorschach tests and things to make us contemplate our place in all of existence ... with the added bonus of looking pretty.

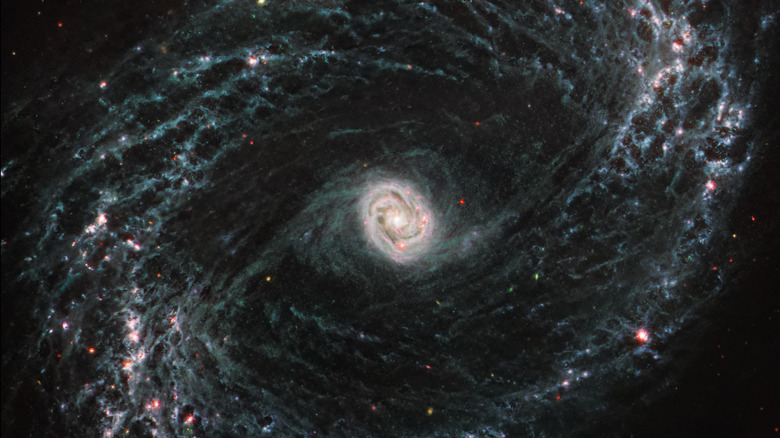

NGC 1433

The NGC 1433 galaxy was originally part of a larger image made up of 18 others, with Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) layering multiple exposures from the system's camera and spectrograph — along with some filters — to bring a bit of color to what would otherwise be in greyscale. This Seyfert galaxy is relatively (in a literal sense) nearby, housed in the Horologium constellation about 46 million light years away from Earth.

This multi-layered spiral cloud has NASA theorizing the presence of some "extremely young" stars, and while it's not immediately apparent from the photo, there's actually a supermassive black hole tucked away in its center. That center also contains a pair of compact spiral arms, which match the direction of the two larger arm-like spirals reaching into the outermost ring.

It can be tough to decide if this image of NGC 1433 evokes a swirling weather pattern — such as a storm — or some kind of cosmic eye, but there's a certain level of eerie beauty to the patterning and the implied movement like a vortex drawing the user in.

Cosmic Cliffs

Anyone with a social media presence has most likely seen Cosmic Cliffs region when it was originally unveiled back in 2022. It's a beautiful showcase of the Webb's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) primary imager, combining multiple images spread across a variety of visual wavelengths.

The result is something that looks like a surreal mountain range beneath (and composed of) a vast sea of stars and other celestial bodies. In reality it's actually a portion of the NGC 3324 region in the Carina Nebula, approximately 7,600 light years out from Earth's orbit. Many of the finer textured details are the result of large quantities of radiation or "eroded" by stellar winds made up of star particles. What looks like mist rolling over mountain peaks is actually a combination of dust and ionized gasses.

Much of the stellar landscape is the result of young stars that are either in the process of aging, or have (in star terms) recently been born. And the "mountain" itself is really the edge of the nebula after being steadily worn down by the radiation emitted from all of those stars.

Pillars of Creation

Once more coming from the Webb NIRCam, Pillars of Creation certainly evokes its namesake. Interestingly, the photo does also embody the title — provided you think about it from a certain angle.

This image of the Eagle Nebula around NGC 6611, in the Serpens constellation about 6,500 light years away, depicts what looks like an assortment of cloud-like pillars (or branches, tendrils, spires, fingers, etc) stretching out into the greater expanse of the universe. These nebula appendages are actually full of young stars that are either freshly "hatched" or still in the process of forming, estimated at being only a few hundreds of thousands of years old. And the waves forming the edges of these pillars are the result of that ongoing star birth and growth.

A combination of the densely packed light emitted from all of those young stars and a translucent cloud of gas surrounding the nebula itself subdues the normally vibrant (and usually more visible) galaxies behind it, making it appear more solitary and cut off. That's just a trick of the light (and gas), though.

Rho Ophiuchi

Rho Ophiuchi isn't an outlier simply because this stellar cloud in the Ophiuchus constellation is much closer to the Earth (390 light years) than any of the other photos we've looked at so far. It's also a much more up-close and detailed depiction of stars being born — which we've definitely seen previously, but not quite like this.

The cloud formation and bright pinpoints of light give the photo a very ethereal quality. As though we're looking at some sort of unknowable entity; perhaps a "small" celestial oasis; or maybe even some kind of divine garment. It's surreal and visually malleable enough to really let your imagination run wild.

What we're actually looking at, however, is a number of new and young stars — generally around the same size as our own sun, maybe a bit smaller — creating the appearance of a bubble made up of various interstellar gasses as they expel energy during their formative centuries.

Webb's First Deep Field

What makes Webb's First Deep Field special is partially in the name itself: This is one of the Webb's first color images, and as packed with detail as it may be, it's still just a tiny fraction of the greater universe. In it, we can see a portion of the SMACS 0723 galaxy cluster, which is over 4 billion (yes, billion) light years away.

It's also like looking through a window in time, because the vast distance between SMACS 0723 and Earth means that what we're seeing is from approximately 4.6 billion years ago — roughly around the time the Earth itself was in the process of forming. We won't know what this galaxy cluster looks like today for a very, very long time.

Due to the weeks-long image capture from the Webb's NIRCam and over 12 hours worth of composites spread out across different wavelengths, we're left with a very clear and intricate photo of thousands of individual galaxies of various shapes and sizes. Also various distances, as the sheer collected gravitational mass of the SMACS 0723 cluster is distorting the light coming from the galaxy clusters behind it, making those even more vastly distant systems easier to see. This is a photo full of an unfathomable amount of star systems, and even then it's still just a fraction of a fraction of a fraction, but it's also the photo that really catapulted the Webb into greater public consciousness.