How Scientists Have Surveyed Over 500,000 Sources To Look For Evidence Of Intelligent Life

It might sound like something that's purely science fiction, but it's a legitimate and busy area of scientific research. Astronomers are attempting to find signs that intelligent life might exist out in the universe beyond Earth. The search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, is a field that has one huge primary challenge, and that's the sheer size of space. Even if there are other civilizations out there, the gulf between galaxies is so large that signals would take millions of years to travel between them.

So to have any hope of finding indications of intelligent life, scientists need to look through an enormous amount of data. Searching as much of the sky as possible, investigating as many cosmic objects as possible, in the hope of finding one that could indicate intelligent life elsewhere.

The typical approach to SETI is to look for what are called technosignatures, which are indications of the use of technology. That includes things like radio waves, which would look different when produced by technological sources as opposed to natural ones. It could involve looking for particular chemicals which are typically pollutants caused by technology such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). And somewhat more outlandish is to look for evidence of advanced technology that humans haven't built yet but have conceived of, such as Dyson spheres which are imagined structures around stars used to harvest energy.

Even with this approach in hand, though, SETI researchers are still facing the numbers problem. They need to comb through huge quantities of data to look for these indicators.

Searching for technosignatures with the Very Large Array

To help with the search for technosignatures, researchers are now making use of the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), a set of 28 massive radio dishes located in New Mexico. These multiple dishes, or antennae, work together to form the equivalent of a single, enormous antenna, allowing them to detect faint signals from distant objects. Each dish is 82 feet across, holds eight receivers, and is mounted on a tripod-style mount which allows it to move and tilt to point at desired objects.

The VLA has a cutting-edge detector called the Commensal Open-Source Multimode Interferometer Cluster (COSMIC) from the SETI Institute, which is specifically designed for SETI research. Described in a paper in The Astronomical Journal, this is a digital tool that can search for technosignatures in a much more comprehensive and efficient way than previous tools, allowing researchers to process large amounts of data more quickly. It is also designed to enable the VLA to be used for other science research while performing its SETI work.

"The COSMIC system greatly enhances the VLA's scientific capabilities. Its main goal of detecting extraterrestrial technosignatures addresses one of the most profound scientific questions ever. This topic was previously not possible with the VLA," said Dr. Paul Demorest of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. "By operating in parallel with projects such as the VLA Sky Survey, COSMIC will accomplish one of the largest SETI surveys ever while still allowing the VLA to carry out its usual program of other astronomical research."

Building for the future

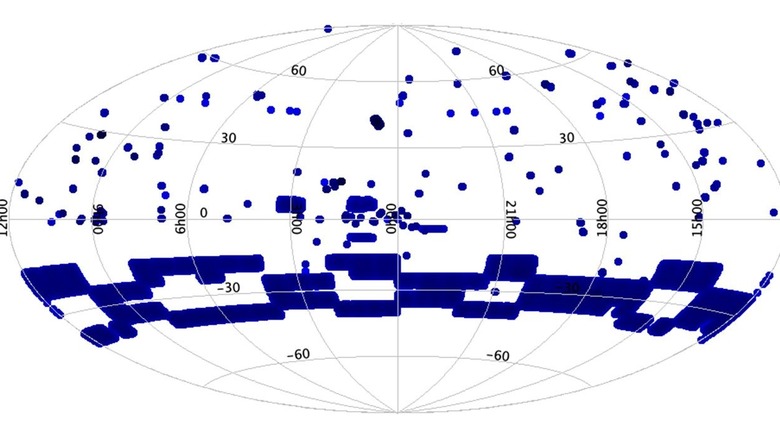

The idea is to use COSMIC to perform a survey of the sky, looking at objects, which are viewed as the array makes its observations, to see if they could be remarkable for SETI. The system has already been used to observe hundreds of thousands of objects, and researchers estimate it will be able to view millions of sources over the next few years.

"COSMIC introduces modern Ethernet-based digital architecture on the VLA, allowing for a test bed for future technologies as we move into the next generation era," said COSMIC project scientist Dr. Chenoa Tremblay. "Currently, the focus is on creating one of the largest surveys for technological signals, with over 500,000 sources observed in the first six months."

The researchers will search through observations from the Very Large Array Sky Survey (VLASS), a wide-scale survey which aims to map 80% of the sky across two years of operations. During that time it will catalog approximately 10 million radio sources.

The big plan for COSMIC, however, is to have it adapt to future technologies. It could be upgraded to look for other signals in different areas of astronomy such as searching for fast radio bursts or dark matter.

"The flexibility of the design allows for a wide range of other scientific opportunities, such as studying fast radio burst pulse structures and searching for axion dark matter candidates," said Tremblay. "We hope to open opportunities for other scientists to use our high time (nanoseconds) or our high spectral resolution (sub-Hz) to complete their research. It is an exciting time for increasing the capabilities of this historic telescope."