These Rare WW2 Photos Reveal The Revolutionary Computer That Helped Defeat The Nazis

In honor of the 80th anniversary of the development of Colossus — arguably the first programmable computer ever made — the U.K. intelligence and security organization known as the Government Communications Headquarters (G.C.H.Q.) has released several previously classified photos of the machine and related documents. The Colossus is a historical artifact not just for being a precursor to modern computers, but for helping the Allied Forces defeat the Nazis in World War II. In fact, secrecy around the machine and its service as a German code breaker had been so strong that this is the first time in eight decades that these photos have been revealed to the public.

The set of computers known as Colossus was developed by British engineer Tommy Flowers, who sought to use the then-advanced computing power of the machine to aid cryptanalysis with help from British mathematician Max Newman. The team that built Colossus worked out of Bletchley Park, an estate in Buckinghamshire, England that served as the headquarters for the Government Code and Cypher School. Information gathered and deciphered by Colossus helped the Allies gain a crucial advantage over German forces, and contributed to their eventual, hard-fought victory in Europe.

[Featured image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]

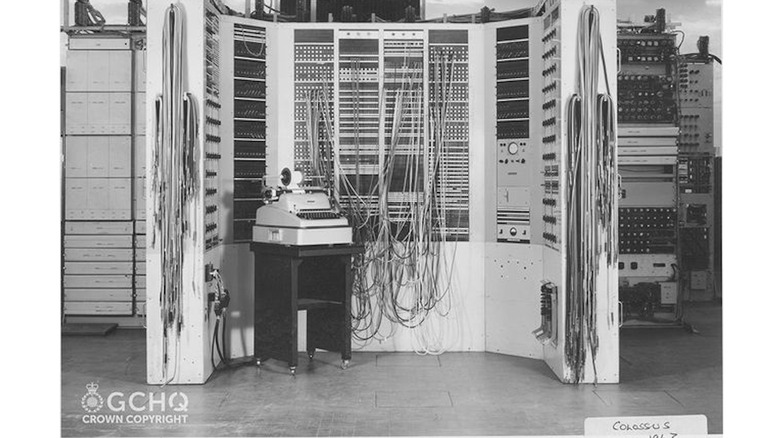

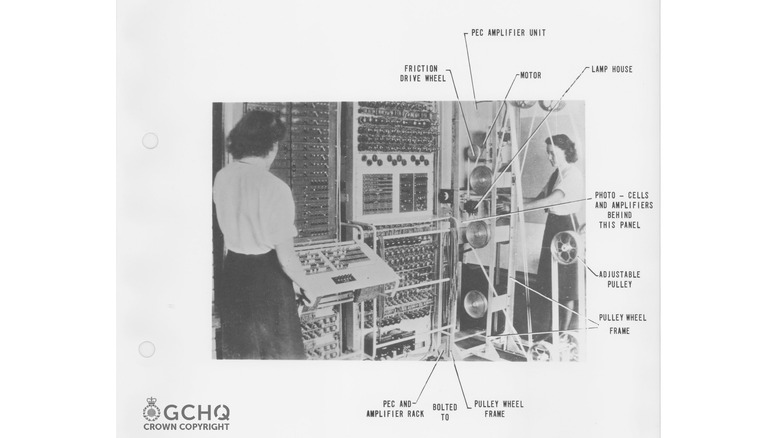

The Colossus was larger than the people operating it

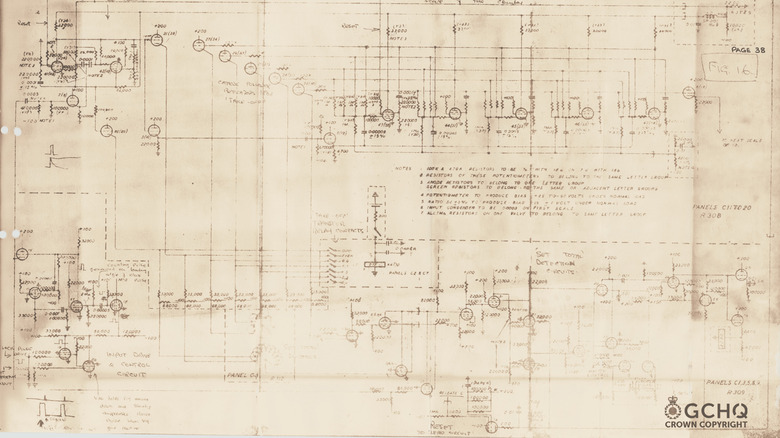

The Colossus, like many early computers, was huge when compared to its modern counterparts, and stood over two meters tall. It used around 2,500 thermionic valves, also known as vacuum tubes, to perform Boolean and counting operations — making it the first-ever digital computer. Rather than using a stored program, it was manually programmed by several plugs and switches.

Data could be input by reading a paper tape transcription of encrypted messages. Because Colossus had no internal storage, the tape was fed in a continuous loop so the computer could read it over and over again. The machine could read 5,000 characters per second and perform five different functions at once, effectively enabling it to read 25,000 words per second. (It could actually work at nearly twice that speed, but the tape would eventually disintegrate.)

The nearly room-sized machine had several large components and required more than one person to properly operate it. It consisted of a tape transport with an eight-photocell reading mechanism, a six-character FIFO shift register, 12 thyratron ring stores, multiple panels of switches for specifying the program and the set total, a set of functional units that performed Boolean operations, a span counter that could suspend counting for part of the tape, five electronic counters, and a master control that controlled clocking, start and stop signals, counter readout, and printing. It was also equipped with an electric typewriter — a precursor to the keyboards most desktops and laptops use to this day.

[Image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]

The intelligence it deciphered helped win World War II

Using codes to transmit messages at risk of being intercepted is a common wartime practice, and the Allies had several different projects dedicated to deciphering crucial information from the enemy, including others that operated out of Bletchley Park. One of those other projects was the Enigma Machine, famously developed by a team led by Alan Turing. However, the Enigma Machine, or bombe, was an electromechanical device that had one function (breaking codes) — not a computer.

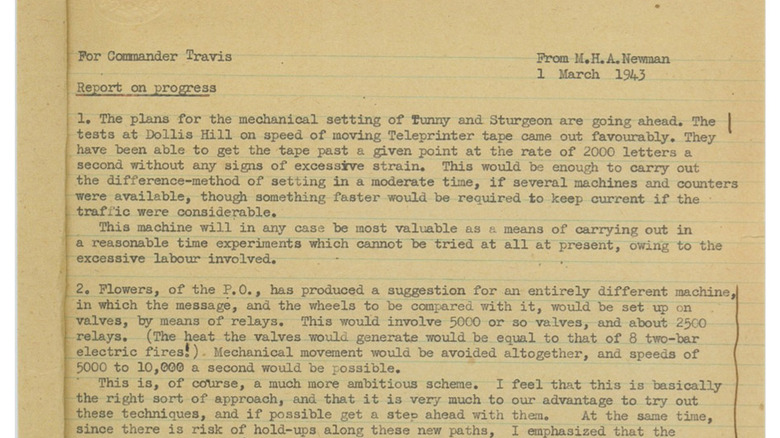

One of the previously classified documents recently revealed by the G.C.H.Q. is a letter from a member of the code-breaking project to a superior officer in 1943. The letter notes that Tommy Flowers had "produced a suggestion for an entirely different machine" that could feasibly be used to break German encryption. That different machine would become Colossus.

Eventually, the early digital machine would begin deciphering vital strategic messages between senior Nazi generals in occupied Europe during the depths of World War II, when such information was more important than ever. The efforts of Colossus even helped confirm that Adolf Hitler erroneously believed the Allies would launch the D-Day invasion from Pas De Calais. Knowing their scheme to misdirect the Nazis was successful had enabled the Allies to go forth with a bold, dangerous plan to take back Europe by storming the beaches of Normandy, while the bulk of German defenses waited for them at Pas De Calais instead. D-Day, of course, was the beginning of the end of the German occupation of France and the war in Europe.

[Image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]

The Colossus was destroyed and its existence kept a secret for decades

While Colossus had helped win World War II, its existence was kept secret long after the global conflict had ended. Intelligence and counterintelligence were vital to the war effort on both sides, which is why codebreaking was so important in the first place. Senior members of the team at Bletchley Park that built Colossus, which had included engineers and codebreakers, had taken oaths of secrecy during the development and use of the early computer. Meanwhile, other expert team members, including those in charge of maintaining and repairing Colossus, were kept in the dark about its true mission, believing they were working on other, unrelated government communications.

But while the Enigma Machine and other codebreaking technology developed during the war were made public once the war was finally over, details about Colossus were kept tightly under wraps. In fact, the British government went as far as destroying eight out of the ten Colossus machines that were built, breaking it down into so many pieces that even if the components were found, the machine couldn't be reverse engineered.

Plus, the team members at Bletchley Park were forced to deliver any and all documentation and other evidence surrounding the Colossus project to the G.C.H.Q. This secrecy was important to the U.K. because the computer was still advanced enough to be utilized by British intelligence after the war, and was employed into the 1960s. As such, information about Colossus wasn't made public until much later — even the photos and documents released by the G.C.H.Q. for the 80th anniversary of the computer have never been public until now.

[Image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]

The Colossus and its developers were at the forefront of the computer revolution

Despite being kept in the shadows for decades, the impact of Colossus was felt around the world throughout the dawn of the computer age, helping build the foundation of a modern society that is heavily dependent on digital technology. According to Andrew Herbert, Chairman of Trustees at The National Museum of Computing, several members of the team led by Tommy Flowers at Bletchley Park "went on to become important pioneers and leaders of British computing in the decades following the war, often leading the world in their work."

Many of those who worked on other codebreaking projects at Bletchley Park, like Alan Turing, also helped shape the future of digital technology, which is why the estate is known today as one of the birthplaces of modern computing. In recognition of its importance, Bletchley Park was chosen as the host venue for the world's first Artificial Intelligence Safety Summit in November 2023, bridging the earliest days of modern computing to the current A.I. revolution and the future of the industry. As a reminder of the legacy of Colossus, a fully functional reconstruction of the code-breaking machine was built and is displayed at The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

[Image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]