From Blitzkrieg To Stalemate: How Tanks Shaped The Course Of WW2

World War I was the most devastating conflict in human history up to that point. It raged for four long years, and on its conclusion, there was hope that such a calamity would never happen again. Tragically, in September 1939, the invasion of Poland brought World War II to the European continent. This war would consume much of the planet for even longer: six years.

Over these six years, territory across the planet was claimed and reclaimed with each new offensive and counteroffensive. The momentum of all of this, however, was wildly changeable, and even the mighty German war machine couldn't simply press forward at top speed at all times. In fact, the period from September 1939 to May 1940 was so devoid of action that it came to be known as the Phoney War.

One big factor in the momentum of combat, of course, is the balance of forces on either side of any given battle. The latest and most devastating weapons, such as tanks, can easily overwhelm a foe if deployed where they can't be effectively countered, but what if weapons of equal potency meet? A protracted stalemate can be the result.

Tanks proved instrumental in the ebb and flow of World War II during both its (in terms of territorial changes) busiest and slowest periods. Here's a look at how things developed in that sense.

The earliest tanks in warfare

The first tanks, effectively, were primarily designed to beat stalemates. When British-designed tanks arrived at the Battle of the Somme in World War I, nothing like them had ever been seen on a battlefield. On an Imperial War Museum podcast, British soldier Philip Neame said his brigade wielded one of the very first tanks: "Everybody was staggered to see this extraordinary monster crawling over the ground."

The objective, for Neames, was "to follow the tank at suitable intervals" and exploit the spaces that the tank would — hopefully — create in opposing fortifications. A shock, blunt-force weapon akin to Hannibal's war elephants in centuries gone by, it was a tool the opposing forces needed to have in their locker, too. The German army developed its own tanks during World War I, and they proved just as surprising to the British. As officer Andrew Bain told the Imperial War Museum, "There were no anti-tank guns in those days. Rifle bullets just skidded off them like peas ... it was rather terrifying to see this thing coming, and you knew that you couldn't stop it."

Later, in World War II, tanks were not primitive, lumbering machines but remained a formidable and almost unstoppable prospect for those unprepared for them. This very fact was central to the concept and the success of Blitzkrieg.

The German army's devastating Blitzkrieg approach

Blitzkrieg, which translates to "lightning war," was the approach the German forces adopted early in the conflict. The core concept is simple: the more time the opponent has to react to your offensive movements, the more prepared and fortified they'll be. Striking hard and fast denies them that chance. The ultimate intent is to use overwhelming force in just the right places, causing a great wave of momentum.

September 1, 1939, saw the German forces invade Poland, and the attack was a prime example of just how relentlessly effective Blitzkrieg could be. It was an invasion on an incredible scale, with around 1.5 million soldiers, 2,315 aircraft, and 2,750 tanks being deployed. The smaller Polish armed forces were also unprepared for the attack and did not have access to the tanks and other weapons (they had just 210,670 tankettes) that would enable them to beat back the invasion. Without support from allies and in the face of an additional invasion from the Soviet Union later that month, the Polish mounted a formidable defense of Warsaw before being defeated.

Both outnumbered and outgunned by their opponents, the Polish forces would witness the sheer power of Blitzkrieg firsthand. Tanks, here, were instrumental to the fast push: the tanks would press, be followed by the infantry, and then press forward again. Without their own tanks or ample anti-tank weaponry, such an assault is incredibly difficult for the opposition to stop.

The Battle of France

In April 1940, an invasion of Denmark saw the country conquered within hours. Paratroopers claimed key areas of Norway in just over a single day, which placed the German army in a commanding position to claim even more of Europe. By May 10, assaults on the Netherlands and Belgium began, and by May 28, both nations had been taken. That day, King Leopold III of Belgium surrendered.

On June 5, following Case Red, the assault on France began. The defenses of the formidable Maginot line were largely overrun, and the push into the country was, again, so swift and decisive that the French couldn't stand against it. Within two weeks, Paris was lost. The armistice was made official on June 22, and it was with an added vindictive pleasure that the German leaders arranged for this to occur in Paris, where the 1918 treaty had been signed.

While all of this was happening, the Allies did not simply sit back. The sinking of the Blücher by Norwegian defenders, the legendary Dunkirk rescue of Operation Dynamo (almost 350,000 Allied troops were successfully evacuated), and the combined French and British assault on the 7th Panzer division at Arras in May all contributed to the fact that the Allies were not taking the opposition's gains lying down. There's no denying, though, that the formidable German panzer divisions shaped these successes and the face of the war at this stage.

Why early Blitzkrieg tactics were so successful

The very concept of Blitzkrieg would swiftly fall apart without communication, and a network of radio communication meant that — ideally, as far as practically possible — ground, naval, and aerial forces knew where to be and where each other would be.

Hitting the Allies as hard as possible was the intent, but the choice of where to do so was vital, too. In dividing the assault on France, for instance, they assured that France had to split its own resources to attempt to defend both its beloved capital city and its Maginot Line defenses, thereby cutting the number of soldiers available for either role.

Said Allies in defensive roles, further, often had inferior equipment to the enemy they fought to repel. The armies of Belgium and the Netherlands were generally poorly armed, with few aircraft, and French defenders at Ardennes lacked specialist weapons to combat tanks. This issue was compounded by the fact that the Allies' own tanks weren't deployed in a concentrated way. As such, during the height of this early Blitzkrieg progress, they couldn't be brought to bear to meet a threat or to pose one in as effective a fashion.

For all of these reasons, the rapid German progress, powered largely by divisions of Panzers and the support of the Luftwaffe, defined the early course of World War II. This would not remain the case, however.

When the momentum ran out

The biggest issue with these high-speed, high-impact tactics, however, was that it wasn't just tanks, troops, and aircraft that had to continuously drive forward. Soldiers and machines alike had to be refueled and maintained, and when supplies couldn't keep up, huge problems ensued. During the North Africa Campaign, the Egyptian city of Tobruk, which had been occupied by the Axis, was rescued from its siege in December 1941, when Major-General Erwin Rommel's forces had advanced too far for the meager desert availability of fuel to support.

This campaign was notable for tank battles, in which the likes of British Crusaders combated Panzer Mk IVs and other models. As this became the shape of warfare, both sides increasingly fought to defend their captured territory from mobile armor specifically. This meant minefields, other defenses, and protracted battles to protect/break past them. In October 1942, victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein was only secured after almost two weeks of combat at the Axis' defenses in the area.

The pace of the war shifted, then, between rapid advances (and retreats) and slow battles of attrition. This was plainly seen during Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Operation Barbarossa

Beginning in December 1940, Operation Barbarossa committed 3.5 million troops, with 3,400 tanks leading the ground assault. Progress, again, was impossibly fast at first, with 1,800 Soviet aircraft destroyed in a single day. The Soviets were surprised, yet again, by the pace of the move and its deadly effectiveness. It took considerable time, given the vastness of the territory, but by the following September had reached Leningrad and Kharkov.

Around then, however, another of the primary issues of these tank-centric tactics came into play: October 1941's assault on Moscow was hampered by an awful freeze and mud that kept supplies from reaching the frontlines. Tank treads, while able to handle the terrain rather better than the wheels of carts, could still make little progress without everything else. It all meant something of a stalemate until the Soviets were in a position to boost their enormous reserves of troops and machinery. A December counterattack pushed the Axis back again.

At this stage, the German forces met their match in tanks. Earlier that year, the German army had reorganized its tank battalions, cutting the numbers of tanks to spread them more widely. The scale of earlier successes meant that there were huge swathes of land to cover, and the majority of tanks available to Barbarossa were lightly armored. This was also true of the Soviets until they unleashed a new weapon.

The shape of the war

The Soviets followed the T-26, the limited firepower they could initially wield during the attack, with the T-34. This new medium tank boasted a 76.2mm cannon, a devastating weapon that was unmatched on the battlefield when it first appeared in 1941 (until anti-tank weaponry advanced enough to penetrate its unique armor). Germany could produce just 250 tanks every month in 1941 while the vast Soviet territories ramped up production.

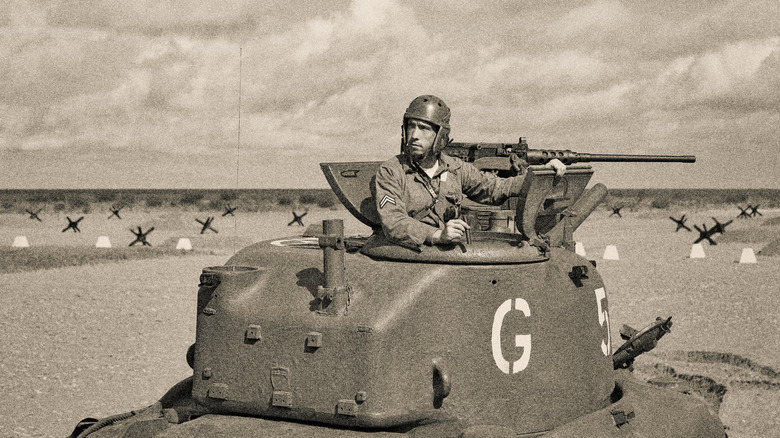

These reserves were crucial for the Red Army. While it sustained enormous losses — almost 480,000 Soviet soldiers were killed at the Battle of Stalingrad alone — it had the numbers to recover from them. Their foes, meanwhile, could not maintain these numbers. In addition, the United States joined the Allied side in 1941, bringing the weight of its own production might with it. The likes of the Sherman tank, of which around 50,000 were developed during the conflict, were crucial weapons to have.

Nonetheless, with both sides continually maintaining and improving their arsenals to the best of their ability, it was some time before a definitive blow was struck. As historian Donald Miller put it at the International Conference on World War II in 2013, "[Late in 1943,] the Germans were losing, and they thought they were losing. We were losing, and we thought we were losing."

Breaking the stalemate

Earlier that year, hoping to overcome the stalemate and claim victory on the eastern front, both sides met at the Battle of Kursk in July 1943. The German forces were equipped with formidable new tanks, such as the deadly Tiger, as heavily fortified as it was armed (an 88mm cannon is a testament to that). The Soviets, for their part, brought 3,600 tanks and an army of around 1.3 million to the fight (not to mention their reserves).

At Prokhorovka, the 5th Guards Tank Army and the II SS-Panzer Corps fought in brutal and protracted tank battles, which resulted in a successful Soviet defense of the city. Though not a decisive victory, the Soviets holding out here meant that a German retreat was necessitated by the Allied advances elsewhere in Europe. As with Japan after the loss at the Battle of Peleliu in 1944, resources were running very low for the Axis, and losses became increasingly difficult to recover as the Allies gained momentum.

Blitzkrieg, then, was a devastating weapon, one wielded to great effect by the German army in the earlier stages of the war. The tanks that were the cornerstone of the tactic enjoyed great victories. However, bolstered by their successes, the Axis pushed themselves too far and could not replace what they lost in the effort. The Allies were forced to work on their own tank strategies to meet the threat, meaning that combat often boiled down to costly shot-for-shot stalemates.