Why The Adams-Farwell Was A Strange And Terrifying Engine

The rotary engine has a misconstrued past. Over the years, the "first" and the "inventor" of it have shifted, and most people don't even realize that the idea for the odd beast actually reaches back over four hundred years.

In the 16th century, an Italian military engineer by the name of Agostino Ramelli came up with the design in 1588 for the first rotary-piston water pump that could raise and lower water "magically" (mechanically). Jump ahead a few hundred years to Scottish engineer James Watt, who took the existing steam engine and improved upon it. Watt converted the drive chain or rod that was customarily used into a heavy flywheel connected to gears, giving it a rotary motion that was smoother and more efficient.

Most folks today credit Dr. Felix Wankel with inventing the modern rotary engine in the 1950s (with the DKM and KKM prototypes) that went on to become Mazda's iconic rotary engine. However, the "true" forerunner is half a century older — and demonstrated for the first time in 1898. It was designed by Fay Oliver Farwell, and built by Herbert and Eugene Adams (the Adams Company) in Dubuque, Iowa.

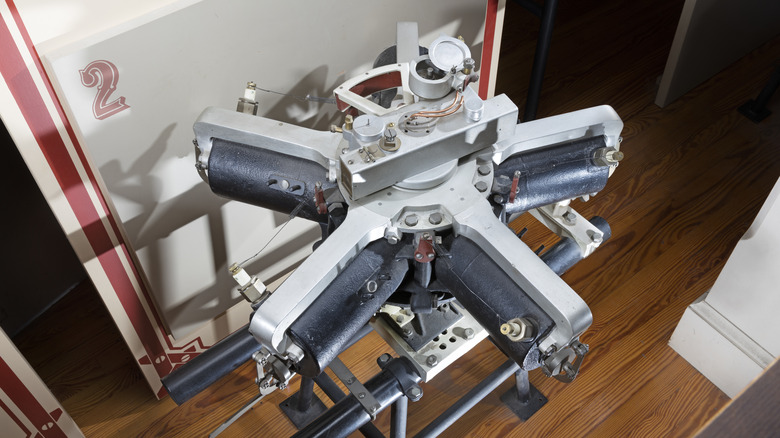

The four-stroke piston engine had three revolving cylinders that spun on a fixed crankshaft connected to the vehicle's frame. It's believed to have powered one of the first vehicles fitted with rubber tires in 1899. One of the main upsides to this engine was that it cooled itself without any additional coolant system. In fact, as the finned cylinder "jugs" spun faster, the engine cooled down even more.

Rotary rage against the machine

Much like James Watt's improvements to the steam engine of yore, the Adams-Farwell 20 horsepower engine provided a much smoother operation because it was well-balanced, had fewer moving parts (i.e., no camshafts), and thus was much smaller and lighter — at just 190 pounds.

An atmospheric carburetor feeds into a specially designed box, down into the engine's center, and out into each cylinder. The centrifugal spin of the cylinders forces exhaust out the back. It takes two revolutions like a standard 4-stroke engine, but fires every other time due to the five cylinder orientation. With oil fed from the center, the engine had full-pressure lubrication.

In 1905, the Adams-Farwell company began selling complete automobiles equipped with the 3-cylinder engine. Only 52 were sold, but they included forward-thinking features like fuel injection, supercharging, and automatic timing. One model even had a top speed of 75 mph. The cars were sold without mufflers because they didn't produce the same degree of noise.

Faye Oliver Farwell repurchased one of his own cars (a 1906 Adams-Farwell 6A Convertible Roundabout) from the original owner and dropped a 5-cylinder, 50 horsepower engine into it. Two of these light weight engines were used to spin the blades on an early helicopter, and according to The New York Times, lifted it off the ground successfully in June 1909.

Only three Adams-Farwell rotary engines are known to still exist: Two are with the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada — one sits inside the 1906 6A, one is a "spare engine" — and the third is at the Smithsonian Institute.