The Black Box: How Flight Recorders Work, And What They Actually Capture

In the high-stakes world of aviation, the black box, officially known as the flight recorder, is recognized as an important device for flight safety and accountability. Black boxes have often been misunderstood and shrouded in mystery, but these devices are fundamental to understanding the intricacies of flight incidents.

We're taking a deep dive into the sophisticated technology behind these crucial tools of the aviation industry, exploring the dual components of the black box: the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) and the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), and how they accurately capture an enormous amount of flight information. From recording pilots' conversations to tracking critical flight data, these devices provide invaluable insights into the mechanics and human factors of aviation. Together, these two devices capture a comprehensive narrative of a flight's journey.

By investigating the layers of flight recorder technology, we can gain a deeper appreciation for their significant role in enhancing flight safety and improving our understanding of air travel when disaster strikes.

The anatomy of a black box

An aircraft's black box consists of two separate systems: the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) and the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR). The FDR logs and stores a wide range of data points for a 24-hour period, including measurements of altitude, speed, engine temperatures, power, flight path, and others. It effectively records any parameter for which there is a sensor or gauge in the aircraft.

The second part of the system is the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR). It captures all radio communications, as well as ambient sounds, through a central microphone. Some systems are even capable of recording sounds from outside the cockpit if equipped with external microphones. Its primary function is to preserve an audio log of all flight activities up until the point of a crash. The device records continuously but only actually saves the last two hours of data.

Both of these devices are designed to simply record and store data and survive extreme temperatures and impacts. Some newer models combine the FDR and CVR into a single mechanism, but it's still very common to see both of these inside a plane. The casing is typically made with steel or titanium to survive the high impacts associated with a plane crash. Inside the casing are the hard drives where the data is stored. The hard drives are then surrounded by sealed thermal insulation to prevent damage in the case of a fire or submersion.

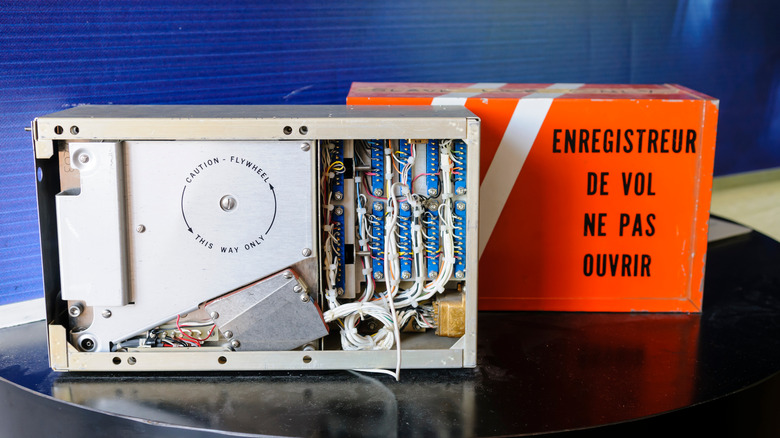

Early black box technology

Flight recorders have undergone various design iterations throughout their history. One of the earliest examples, from 1939, was quite basic, functioning by photographing instrument readings. A major breakthrough came in 1954 with David Warren's invention, the first modern flight recorder, which electronically logged flight data and cockpit conversations.

The initial flight recorders used photographic paper, a method later replaced by magnetic tape in the 1960s. However, both these storage mediums had notable limitations, such as the need for increased maintenance and regular replacement to maintain consistent data recording.

The transition to digital memory chips in the 1990s marked a significant improvement in flight recorder technology. These chips were superior in many ways, particularly because they allowed data to be overwritten after each successful flight, significantly reducing maintenance requirements.

The rise of commercial aviation after World War II, bolstered by its surge in popularity as a travel method, brought new challenges. Most early flight accidents were attributed to human error, and without survivors, it was often difficult to ascertain the exact causes of these crashes. This predicament led to the creation and gradual refinement of flight recorders, known colloquially as black boxes, which became essential for investigating plane crashes and enhancing overall flight safety.

Delving into the FDR: Capturing the aircraft's story

The Flight Data Recorder (FDR) plays a crucial role in any aviation crash investigation, providing extensive data. Current Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations mandate the recording of 88 distinct data points, although some FDRs are capable of capturing even more. The FDR logs a wide range of information, including altitude, heading, speed, and the status of the autopilot. While some of this data might seem inconsequential, it becomes vital in the event of a crash.

Investigators use the comprehensive data from the FDR to construct an accurate 3D model of the aircraft's movements and actions. This model helps answer key questions, such as whether the pilot overcompensated with the controls, thereby aiding in determining whether a crash was caused by mechanical failure or pilot error.

A notable example is American Airlines Flight 587. Following the crash, which occurred soon after the events of 9/11, there were initial concerns about another terrorist attack. However, analysis of the data from the FDR conclusively showed that the cause was pilot error. The tragic loss of lives onboard and on the ground was a profound event, but the clear evidence from the FDR helped prevent further nationwide panic.

The CVR: Preserving the voices of the cockpit

The Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) is the second essential component of a flight recorder system. It includes a dedicated microphone that constantly captures sounds inside the cockpit, including all communications transmitted through the airplane's radios. This isn't just a morbid curiosity but an integral part of the system. Having the firsthand account of the pilots on record can be another way to determine what went wrong and, hopefully, prevent future accidents.

A stark illustration of the CVR's importance is the case of Aeroflot Flight 593. Analysis of the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) data alone made no sense to investigators. The plane was functioning perfectly fine but then suddenly began to bank and turn off course. It eventually stalled when the pilots tried to overcompensate, and ultimately, it spiraled down and crashed, killing all aboard.

The narrative from the CVR, however, told a different story. It revealed that the captain had allowed his teenage children to enter the cockpit and simulate flying. Unknowingly, they deactivated the autopilot while handling the control stick. Tragically, by the time the pilots realized what had happened, it was too late for them to avoid disaster. In this case, without the CVR recording, there would be nobody to tell the tale and consequently reinforce regulations that could save lives in the future.

The retrieval and analysis process

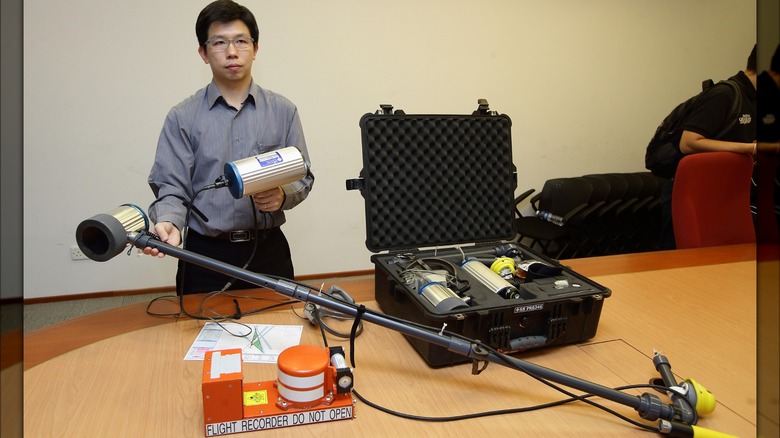

Contrary to their nickname, flight recorders, also known as black boxes, are actually painted bright orange and covered with reflective tape. This color choice is intentional as it makes them easier to locate after a crash. These devices are built to withstand extreme impacts, prolonged submersion in water or fuel, and high-pressure depths, making a dark color like black impractical for visibility.

The challenge in recovering flight recorders often lies in pinpointing their location, particularly because they are usually stored in the tail section of the aircraft. In situations where the plane breaks apart in mid-air, the recorder may land several miles away from the crash site. This is a common occurrence in crashes over vast bodies of water.

When a flight recorder lands in the water, a special feature is activated: a device that emits ultrasonic pulses to assist in its recovery. This beacon can send signals every second for up to 30 days, powered by its self-contained battery.

In some instances, recovered flight recorders are kept submerged in containers filled with water. This method is employed to prevent damage from saltwater and other minerals, which could harm the recorder's contents if they were to dry and form deposits. Keeping the recorder submerged safeguards the data until it can be safely extracted and analyzed.

The impact of black boxes on aviation safety

Flight recorders and black boxes have significantly improved airline safety since their introduction. Many of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations are the result of thorough investigations and insights gained by analysis of previous crashes using data from flight recorders.

The FAA is also considering adding a potential new regulation that would mandate black boxes to increase their capacity from two hours to 25 hours of data. If implemented, this would be a significant victory for the National Transportation Safety Board, which has been advocating for this change since 2018.

These recorders are mandatory on all commercial flights and play a significant role in continually improving aviation safety, even preemptively. Beyond commercial aviation, flight recorders are crucial in experimental and test flights. They capture a wealth of data, including pilot actions and experiences, during these flights. This data not only provides a detailed record of the flight but also allows for thorough analysis, which is vital to identifying potential advancements and refining flight safety protocols and procedures.

This continuous cycle of data collection, analysis, and application is key to advancing flight travel, enhancing efficiency, and elevating safety standards in the aviation industry.

The future of black boxes

Black boxes are an important part of the safety and accountability features in the aviation industry. Finding the cause of a crash can help prevent future crashes and determine the underlying cause of an incident.

However, as previously mentioned, their effectiveness hinges on their ability to withstand the crash and subsequently be located. If you haven't been on a major airline flight in the last few years, you may not be aware that many now offer full-service Wi-Fi on certain flights. The technology and infrastructure are available for the flight crew to stream large amounts of data, even from 30,000 feet in the air.

This has sparked a proposal to live-stream flight data to a secure cloud or server, bypassing the need for a physical black box that might be damaged or lost in a crash. In theory, this would ensure the data's continuous availability.

However, this idea has faced a certain amount of criticism. Detractors argue that the technical challenges, such as potential gaps in satellite coverage or data blackouts in extreme weather, could disrupt the stream during critical moments. There's a significant concern regarding cybersecurity, too. They believe that live-streaming data could open up flight controls to hacking, potentially exposing the cockpit and its systems to security risks.

Despite these debates, the role of black boxes in the future of aviation is clear. They will continue to be a key tool in helping investigators understand flight incidents, contributing to improved safety measures, and potentially saving lives.