GM And Stellantis Look To US-Made Electric Motor Tech To Win The EV Price War

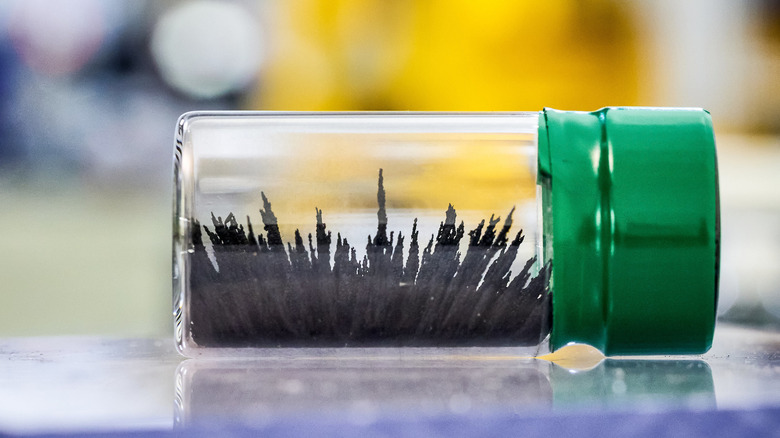

General Motors and Stellantis are hoping to fix a glaring hole in their electric vehicle roadmaps, with the two automakers setting their sights on a US-made magnet tech that could upend the motors used in future electric vehicles. Rather than increasingly costly rare-earth minerals, which U.S. automakers must typically source from abroad, the iron nitride magnets are said to be the first permanent magnets with automotive-grade power.

It's the handiwork of Niron Magnetics, a spin-off of the University of Minnesota, which has raised $33 million in new funding from investors including the two automakers. GM and Stellantis aren't the only automakers sniffing around Niron's tech, mind. Volvo previously claimed a stake in the company, with an earlier investment from its Volvo Cars Tech Fund.

The appeal for a carmaker, of course, is clear. Current electric vehicles typically rely on permanent magnets that use rare-earth materials. Not only are these in relatively short supply and expensive, but they also come with supply-chain headaches including dependency on foreign mining and production. Niron's so-called Clean Earth Magnet, in contrast, could be produced from abundant iron and nitrogen, and in the U.S.

Domestic EV production is potentially lucrative

Domestic production of EV components has become a topical issue in recent years, not least because of the increased focus by the U.S. government on subsidizing only vehicles that are built in America. Where the criteria for the old EV federal tax incentive centered on factors like battery size, the latest iteration of the policy demands qualifying vehicles be assembled in North America and meet critical mineral and battery component requirements.

It was a change that saw multiple EVs suddenly drop off the eligibility list, a shakeup worth up to $7,500 of incentives on the cost of a new vehicle. Several automakers responded with plans to produce their EVs at North American facilities, but the reality of the rare-earth materials supply chain has made domestic battery production tricky.

Eventually, so the automakers hope, Niron's technology could help fill that gap. It's too early, representatives from GM said ahead of the investment announcement, to say whether iron nitride-based magnets could replace rare-earth magnets entirely. However, the technology is promising, they insisted, and even a partial success would help broaden the supply chain and reduce dependence on any one material or its source.

Upending EV magnets is an expensive business

Before that can happen, Niron will need to scale up considerably. The company plans to spend the $33 million funding on things like larger-scale equipment to ramp its manufacturing, though even then it may not be vehicles that are the first recipients.

Instead, Niron CEO Jonathan Rowntree says, consumer technology and audio products could be early beneficiaries. The company also envisages its magnets showing up in future wind turbines and industrial motors. Eventually, Niron is confident that its magnets can be price-competitive with rare-earth magnets available today.

Actually achieving that, though, takes some serious investment. Niron has been working on the Clean Earth Magnet technology for a decade now, with just over $100 million in funding during that period. Around a third of that is from government grants, from the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense. With this fresh injection, the goal is to go from pilot production to scale manufacturing, with Niron working with GM as its "lead automotive" strategic partner for electric motors to be used in upcoming Ultium-based EVs.

The tech may be solid, but the roadmap is murky

It won't be a simple swap. Iron nitride definitely has advantages: It is, Rowntree points out, more magnetically strong than the alternatives, with 2.4 tesla of strength compared to the roughly 1.6 tesla of commonly used rare-earth magnets. Its constituent materials have 70-80% less impact on the Earth, too, the Niron CEO claims, and demonstrate improved temperature stability.

However, they're not a drop-in replacement for current magnets in existing motors, and while Rowntree suggests there are "opportunities there to improve motor efficiency" with new designs, it does mean more complexity than had they been a like-for-like swap.

As a result, nobody is ready to say when motors based on iron nitride magnets will actually be commercially ready, nor to do a direct cost prediction compared to the currently available motors. In short, like so many potentially game-changing tech advancements promising to upend the EV segment, this is unlikely to do anything to sway the electric car you might have on your shopping list in the near future.