Lake Nyos Disaster: The Science Behind The Deadly Lake

When people talk about volcanos, it's common for others to picture the kinds of apocalyptic eruptions often shown in disaster movies — as well as, unfortunately, in recent news. While these ancient and natural formations may not be the geological monsters Hollywood usually depicts them as, nor are they all "an accident waiting to happen," they and the areas around them do contain elements of danger. Danger that can sometimes be lethally subtle.

In August of 1986, one such quiet tragedy hit the homes and villages surrounding Lake Nyos, located in the Central African country Cameroon. At around 9 p.m. that evening, the small lake formed in the crater of a dormant volcano expelled a cloud of carbon dioxide gas large enough to reach areas more than 15 miles away. This toxic cloud resulted in the deaths of over 1,700 people, thousands of heads of cattle, and most of the wildlife.

Carbon dioxide itself is an important greenhouse gas as it helps to regulate the planet's temperature, but in high enough quantities, it can also be fatal to all forms of animal life. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, Lake Nyos had been holding in immense amounts of the substance for a very long time.

Where it came from

A buildup of carbon dioxide gas is not uncommon for crater lakes, with many of them occasionally releasing bubbles of it over time. Volcanic activity taking place below the Earth's surface (and below the lake itself) will cause gasses to seep up through the lakebed and into the water. Something that generally isn't a concern as deeper, colder water is able to absorb substantial amounts of carbon dioxide, but if the concentration gets too dense it can create bubbles that float up to and burst on the surface of the water.

This in itself is common, and the volume of carbon dioxide usually released in this manner will dissipate into the air quickly. However, it's theorized that Lake Nyos had been amassing an uncharacteristically large amount of gas due to a combination of factors like location, local climate, overall depth, and water pressure. Once that buildup had been disturbed, it all came rocketing out.

Whether it was due to a rock slide, strong winds, or an unexpected temperature change throwing off the delicate balance is still unknown. But whatever the catalyst was, it caused the lower layer of deep, carbon-infused water to start to rise. Which then began to warm up, reducing its ability to contain the gas. The resulting perpetual cycle of rising waters and gasses creates the type of explosion you might see after opening a carbonated beverage after it's been shaken vigorously.

How it spread out

After the gas cloud erupted, it reportedly began to spread across the landscape at speeds between 45 and 60 miles per hour. The nearest villages and farms were hit almost immediately, with outlying areas within that estimated 15-mile radius following shortly after.

With Lake Nyos located on a topographical incline, the carbon dioxide (which is heavier than oxygen) flowed down into the nearby valleys and over the villages of Cha, Fang, Mashi, Lower Nyos, and Subum. With nothing but a vague rumbling sound (according to eyewitness accounts) to act as a warning that something was wrong.

Due to the carbon dioxide concentration, every person and animal caught in its spread passed out almost immediately, most of whom passed away within seconds. Those who were lucky enough to inhale a lower concentration of the deadly cloud — possibly due to winds blowing it away from them, being in a space with poor ventilation keeping most of the carbon dioxide out, or a higher elevation keeping them above the worst of the denser gas — woke up several hours later.

Could it happen again?

As tragic and unexpected as the Lake Nyos incident was, it's not impossible to think that something similar could happen again — either at Lake Nyos itself or at one of the many other volcanic crater lakes around the world. In fact, it had happened two years before at the nearby (but smaller) Lake Monoun. However, it's also not an inevitability, and scientists have been working on ways to avoid a recurrence.

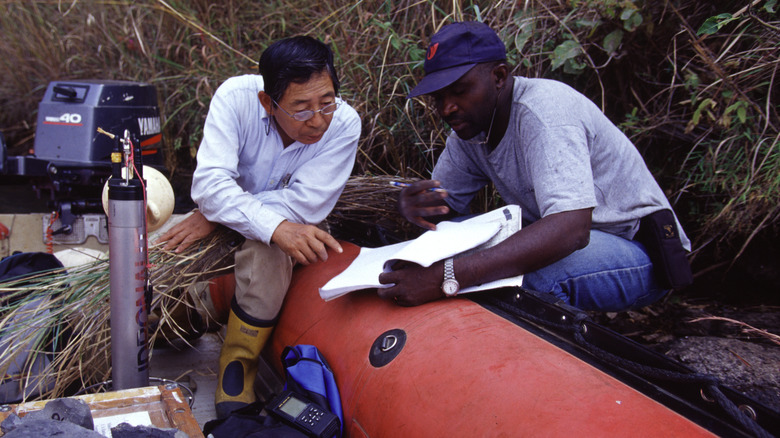

CO2 monitors were installed in the area surrounding the lake, ready to sound warning sirens if the buildup gets close to 1986's levels. In addition to an early-warning system, several pipes have been installed in order to allow Lake Nyos to vent carbon dioxide at a steadier (and safer) rate, in the hopes of preventing any more dangerous buildup. Several other lakes have been examined in the intervening years to check for warning signs, as well.