10 Of The Worst Military Bombers Ever Made

The world's superpowers once considered the bomber to be the key to maintaining strategic airpower. During the WWII years, the air forces of the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Italy placed a priority on bomber development. However, their efforts did not always produce effective military weapons and some designs were fundamentally useless.

Most military experts will agree the B-2 Spirit makes the top of the best list with a combination of characteristics that strikes fear in the hearts of its adversaries. Capable of multiple missions, the B-2 uses a generic weapons interface system (GWIS) allowing the bomber to carry a mix of stand-off weapons and direct attack munitions for up to 40,000 lb of payload. The aircraft has a range exceeding 6,000 nautical miles unrefueled and can soar to a maximum altitude of 50,000 feet while carrying both conventional and nuclear weapons.

Even for the best bomber aircraft, time is often the enemy, eventually outperformed by more modern airplanes. The heralded B-29s that dominated the airspace over Japan in 1945 were no competition for the more advanced fighters in the Korean War. These are 10 of the worst military bombers ever made, either for their poor design and construction or their loss of effectiveness with time.

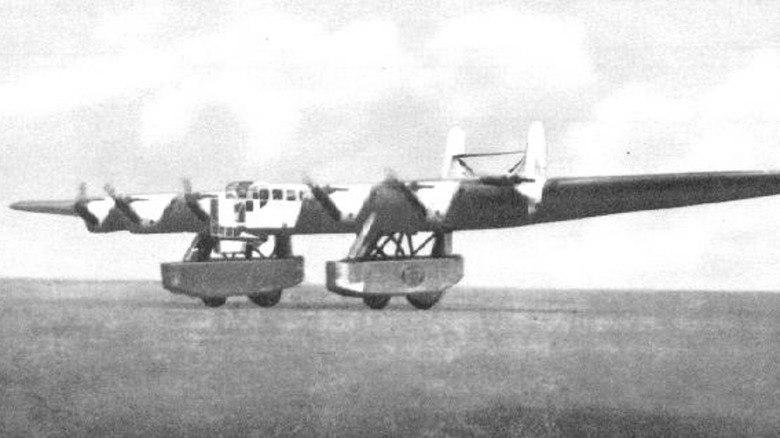

Kalinin K-7: Russia

Designed by World War I aviator and Soviet aircraft designer Konstantin Kalinin, the K-7 was one of the biggest airplanes of its era. The massive experimental aircraft had enormous wings measuring 196 feet long with leading edges over 7 feet thick. The flying wing design featured six engines attached to the wings and a seventh engine mounted on the back of the wing as a pusher. The K-7 was fitted with underwing landing gear pods that hosted machine gun turrets. Inside the wings, the K-7 accommodated 128 passengers with sleeping quarters for 64 passengers, a smoking lounge, a small restaurant, and 16 furnished staterooms.

Although the K-7 represented the most luxurious form of air travel in the early 1930s, the airplane was also designed to function as a long-distance heavy bomber and troop transport plane. The massive aircraft had a weapons payload capacity of 9.6 tons. The size and fuel capacity made it ideal for reaching Russia's remote locations without the need for refueling. The sheer size of the aircraft was made structurally viable with the use of chrome-molybdenum, a lightweight steel with a favorable strength-to-weight ratio, instead of the traditional aluminum or fabric-covered wood.

However, this flying fortress was destined to fail. In 1933, the K-7 made seven test flights. During a flight on November 21, a structural failure in one of its booms caused the cumbersome plane to crash, killing 14 crew members. Although the Soviet Air Force had planned to build two additional prototypes, the project was canceled after the disaster.

Tupolev Tu-22: Soviet Union

Introduced in 1962, the Tupolev Tu-22 medium-range supersonic bomber was a disappointment from its beginning. Not only did it lack the speed and range the Soviet Union Air Force had requested, but it was also plagued by a plethora of design flaws and unreliable VD-7M turbojet engines that resulted in several fatal accidents.

Tupolev built the Tu-22 with high-swept wings. However, while this design concept can be very effective at high speeds, the Tu-22's swept wing resulted in poor handling at subsonic speeds and required a long runway for take-offs due to the low lift generated at slower speeds. Beyond that, the long, pointed nose, housing the navigation and attack radar kit, made runway visibility difficult.

The unique cockpit seating had the pilot on the left, the weapons officer slightly to the rear, and the navigator inside the plane's fuselage below the pilot. In case of emergency, the navigator's ejection seat exited the bottom of the jet. Some of the first Tu-22s experienced damage from a tail strike upon lift-off. The airframe skin frequently overheated during supersonic flight, adversely affecting the flight characteristics and the control system. Tu-22 pilots needed exceptional physical strength, always keeping both hands on the control yoke to maintain control.

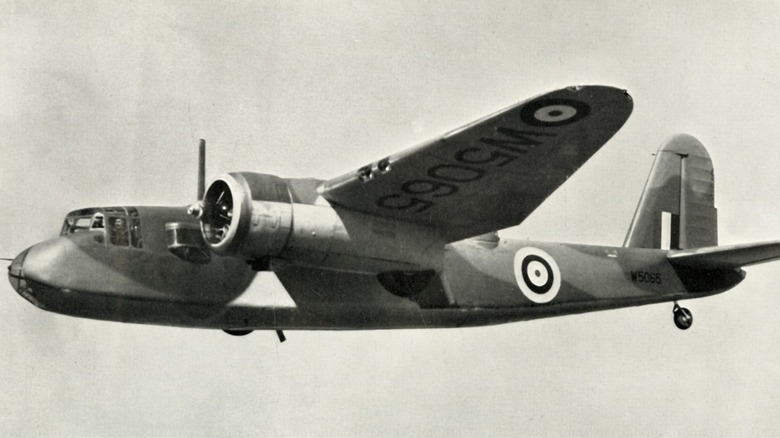

Blackburn Botha: Great Britain

When the RAF first tested the Blackburn B-26 Botha reconnaissance and torpedo bomber on December 28, 1938, the aircraft performed poorly. Results showed that the aircraft lacked longitudinal stability, poor elevator control, and a high stalling speed. Several other issues were troublesome, including exhaust fumes pouring into the cockpit.

Two 880 hp Bristol Perseus X (930 hp Perseus XA on later aircraft) engines provided power giving the aircraft a maximum speed of 220 mph at 15,000 ft and a range of 1,270 miles. Botha's armament included a forward-firing Vickers machine gun, two Lewis MkIII guns mounted in the rear, one 18-inch torpedo or 2,000 pounds of bombs. When fully loaded with weapons, the Botha, carrying four crew — pilot, wireless operator, navigator, and gunner — suffered from a significant lack of power. Although 580 units were built from 1939 to 1944, the aircraft's poor performance meant that during the war it provided full operational service with just one squadron.

The aircraft conducted reconnaissance patrols in the non-threatening North Sea for only six months in 1940 until it was pulled from the front. The Botha never entered service as a torpedo bomber, for which it was designed. The RAF subsequently assigned 478 airplanes to training establishments in support of reconnaissance, navigation, bombing, and gunnery exercises, while several aircraft were used for target tugs. By the time the Botha was retired, an incredible 169 units were involved in accidents.

Convair B-58 Hustler: United States

Introduced on March 15, 1960 and retired just a decade later, the Convair B-58 Hustler's delta wing, giant engines, and remarkable performance promised to make a significant impact on the effectiveness of the modern-day bomber. The B-58 boasted several ground-breaking features for strategic bombers. The wings swept 60 degrees, spanned 56 feet, and the aircraft reached a length of 96 feet and 9 inches. It was fitted with four turbojet engines with afterburners mounted outboard on the wings — a first for a supersonic aircraft.

The B-58 could break Mach 2 and reach a range of 3,500 nm flying at a high altitude while equipped with a large centerline fuel pod covering one nuclear weapon. The aircraft lacked a bomb bay but could carry four weapons (nuclear or conventional) on external hard points. The engineering masterpiece was faster than Soviet fighters of the era and held several speed records. However, the advent of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) in the late 1950s (the Soviet S-25 SAM system was developed shortly after the American Nike Ajax system) forced the B-58 to adopt a revised mission profile focused on low-altitude flights to avoid detection by the enemy.

The new missions augmented fuel consumption and negatively impacted the bomber's range. Beyond that, as was typical of many early delta-wing aircraft, the B-58 Hustler was difficult to fly. The airplane employed many specialized systems and complex controls, resulting in unconventional take-offs, landings, stalls, and spin characteristics that were hard for even experienced pilots to master. The B-58 also generated exorbitant maintenance costs and experienced an excessive accident rate. The Air Force acquired 116 B-58s during its brief 10-year service, of which 26 were lost to accidents.

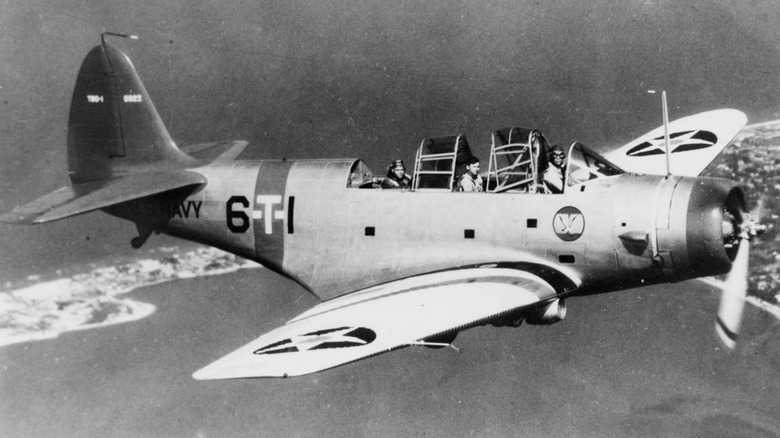

Douglas TBD Devastator: United States

The TBD Devastators were considered one of the U.S. Navy's best torpedo bombers when Douglas delivered them in 1937. However, by the time the U.S. entered WWII with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the aircraft was already outdated. The bomber was slow and lacked the defensive capabilities needed to combat the Japanese Zeros and the anti-aircraft guns on Japanese ships.

A three-man crew, including a pilot, navigator/bombardier, and radioman/gunner, sat under a large, distinctive greenhouse canopy. To aim the bombs the bombardier lay in a prone position sighting the target through a window behind the engine. The aircraft reached 35 feet in length and the wings that folded upward for carrier stowage spanned 50 feet. Power was delivered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1830-64 Twin Wasp 14-cylinder two-row air-cooled radial piston engine generating 900 hp.

The TBD Devastator achieved a maximum speed of 206 mph and had a range of 450 nm when the payload included a torpedo (1,200 pounds) or 900 nm when loaded with a lighter (typically 1,000-pound) bomb. Weapons included a fixed .30-caliber gun that fired forward and a flexible .30-caliber gun mounted in the dorsal position. Not only was the bomber slow, but to drop a torpedo it had to fly at a reduced speed of 115 mph. The TBD Devastator's combat record was dismal, to say the least. The last combat mission for the torpedo bomber was the Battle of Midway in 1942, during which 41 TBD Devastators were sent into action, but only four returned.

Messerschmitt Me 210: Germany

The Messerschmitt Me 210 might have been Germany's biggest aircraft failure of World War II. The Luftwaffe pulled the fighter/bomber from service just a year after it was introduced due to severe instability, frequent loss of control, and sudden stalls.

A two-person crew flew the Me 210, which featured a length of 40 feet, a wingspan of 53.5 feet, and a maximum takeoff weight of 21,396 pounds. Two Daimler-Benz DB 605B V-12 inverted liquid-cooled piston engines produced 1,455 hp each for a maximum speed of 360 mph. While all of this was impressive, during level flight the aircraft veered back and forth, making it difficult to aim the guns or drop ordnance accurately. It was unstable through turns and had a center of gravity too far to the rear of the aircraft, which caused the nose to rise at slower speeds. During a slow-speed turn, the plane risked stalling and falling into a dangerous spin.

Messerschmitt made substantial modifications to the aircraft's tail to improve performance, but the instability persisted and the airplane manufacturer was forced to redesign the fuselage and wings. A few of the poor performance issues were improved, but the overall poor performance persisted. Only 357 aircraft were built in Germany before the Luftwaffe halted production in 1944.

[Featured image by Hönicke via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Heinkel He 177 Greif: Germany

The design and manufacture of the Heinkel He 177 Greif resulted from Adolf Hitler's request for a bomber with sufficient range to attack London and Allied convoys in the Atlantic by day or night. The Luftwaffe's original specifications requested a heavy bomber with a maximum speed of 335 mph, a 4,400-pound payload at 1,000 miles, or a 2,200-pound payload at 1,800 miles. Furthermore, the aircraft must have the structural integrity to conduct anti-ship dive-bombing missions.

While the He 177 Greif showed promise during the design phase, in the early stages of production it quickly became one of the most troublesome German aircraft of the war. The Heinkel He 177 Greif employed a unique engine design that paired two engines to each of two propellers. The complicated power delivery system offered several sources of overheating and risk of fire — in fact, when all was said and done more Heinkel He 177s were lost to fire than enemy combatants.

In addition to the propensity to burst into flames, tests on the first production A-1 He 177 Greif revealed that the wing had been improperly designed and structural failure would begin after a mere 20 flights. A redesign to strengthen the wings added weight and delayed production time. Despite these issues, Heinkel built more than 1,000 He177 Greif aircraft before production ceased in July 1944.

[Featured image by Heise via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Fairey Battle: Great Britain

The three-seat, single-engine British light bomber Fairey Battle, designed and built in the early 1930s, showed great promise at its introduction in 1937. The aircraft could carry twice the ordinance over a much longer distance than its RAF predecessors, the Hawker Hart and Hind bombers. However, by 1939, the bomber was already obsolete, outperformed by the more modern bombers of the Luftwaffe. Lacking a suitable alternative aircraft, the RAF was forced to keep the outdated aircraft in active service into the early years of World War II.

Over 2,000 airplanes were produced from 1936 to 1941, including those built for use in Canada, Belgium, South Africa, and Turkey. Powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin I engine producing 1030 hp, the Fairey Battle had a cruise speed of 211 mph and a maximum speed of 258 mph. The aircraft had a service ceiling of 25,000 feet and was equipped with a single .303 Browning machine gun in the front and a Vickers K in the rear position. The 1,000-pound plus bomb capacity was typically divided between four 250 lb bombs in the internal wing space with the option of adding 500lb of bombs mounted to under the wings.

The slow speed and lack of advanced defensive armament made the Fairey Battle inappropriate for unescorted daylight operations. These ill-equipped bombers showed their vulnerability in May 1940 when over half of the 118 engaged aircraft were lost within a short four-day period.

Convair YB-60 Bomber: United States

Immediately following the end of World War II, the U.S. Air Force sent out proposal requests to military aircraft manufacturers for a new strategic military bomber built with turbojet engines to provide more speed than conventional propeller-powered aircraft. The USAF wanted a heavy bomber capable of carrying atomic bombs a long distance across oceans. Convair proposed a jet-engine version of its piston-engine B-36, created by simply swapping out the engines. However, the aircraft required much more, a change of nearly a third of the components.

The YB-60 bomber is 171 feet long, 50 feet high, and spans 206 feet. The eight Pratt & Whitney XJ57-P-3 turbojet engines generate 8,700 pounds of thrust each, mounted in pairs under the wings. They produced a cruising speed of 435 mph along its range of 2,900 miles. Five crew members (pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier, tail gunner) fly the YB-60 to its maximum service ceiling of 52,000 ft. while carrying a bomb payload of up to 72,000 pounds.

Initially, the YB-60, the bomber boasted some impressive performance numbers but faced insurmountable competition from the Boeing B-52. The Convair's larger payload resulted in a top speed that was significantly slower than that of the B-52, and Boeing later added the "big belly" modifications to give its bomber a 54,000 pounds payload capacity. These factors led to the Air Force canceling the YB-60's test program in January 1953.

Handley Page Heyford: Great Britain

Although an experimental version of the Handley Page Heyford was the first airplane to carry radar, the aircraft had a dismal record as an RAF bomber. First flown in June 1930, the last of the RAF's biplane heavy bombers left active service in No. 166 Squadron at Leconfield in Yorkshire on September 2, 1939, without ever having dropped a bomb or fired a gun in combat — one day before war officially broke out between Great Britain and Germany.

The open-cockpit Heyford measured 58 ft in length and boasted a wide wingspan of 75 ft. The forward area of the main fuselage was metal while the rear fuselage was covered in fabric. While typical biplanes of the era were built with the fuselage attached to the lower wing, the Heyford had its fuselage mounted to the upper wing giving it an awkward appearance. However, the design provided the pilot and the aircraft defensive gunners with an unobstructed field of vision.

The first Heyford aircraft were equipped with two Rolls-Royce 575 hp Kestrel IIIS, 12-cylinder piston engines providing enough power to reach a maximum speed of 142 mph. The biplane operated with a maximum ceiling of 21,000 ft. Although they were sturdy, agile aircraft with low maintenance and could even be looped, the RAF replaced the Heyford biplanes with Whitley bombers in 1939. However, 40 airplanes remained in service until August 1940, used for bombing training and towing aerial targets during gunnery firing exercises.