Project Pigeon: How Birds Were Trained To Guide Bombs In WWII

While pigeons and doves are the same species, many people consider the former little more than rats with wings. They roost in cities, gather around anyone with food, and poop on everything. But not too long ago, we relied on pigeons for help during warfare — ironic given that doves are a symbol of peace.

Before the invention of walkie talkies, satellite phones, and other long-distance communications, soldiers used pigeons to ferry messages across the battlefield. Homing pigeons were prized for their unerring ability to quickly find their way back to HQ no matter the distance, as well as their unflappable resistance to stressful conditions. These message-carrying birds were so reliable that they were used up until 2006, but they arguably saw their most action during the world wars. Given the widespread use of pigeons, some innovators thought up new ways to weaponize these creatures. What do a psychologist, the U.S. military, and a food company all have in common? They all thought pigeons could be strapped into the heads of missiles and tap on glass screens that projected images of targets in order to guide their explosive payloads.

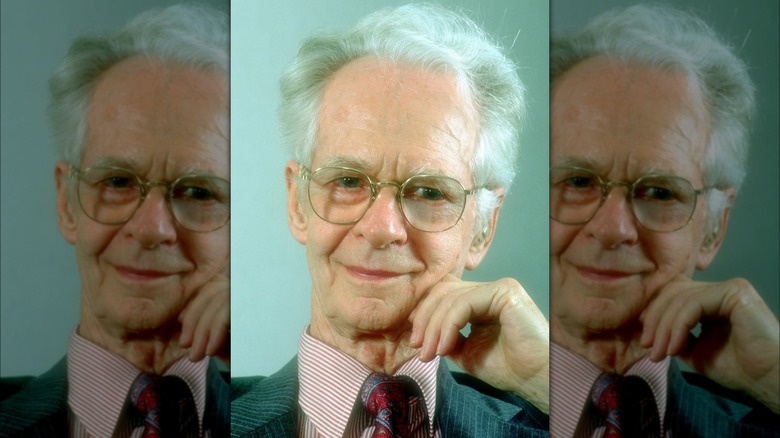

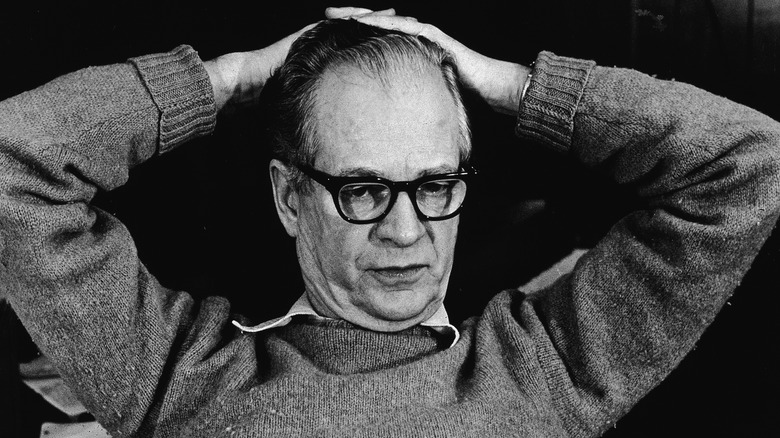

This not-so featherbrained plan never came to fruition, but the story behind its ups, downs, and eventual failure is, well, quite the story. To quote its creator, B.F. Skinner, "This is the history of a crackpot idea, born on the wrong side of the tracks intellectually speaking, but eventually vindicated in a sort of middle class respectability."

Just Who Is B. F. Skinner?

The plan to use pigeons to steer missiles, better known as Project Pigeon, was the brainchild of psychologist B.F. Skinner. But you might know him as the father of Operant Conditioning and the Skinner Box, both of which played crucial parts in Project Pigeon.

Skinner's theory of Operant Conditioning relied on the assumption that creature behavior is the result of their environment, and the consequences of certain actions affect the chances of them repeating said behavior. If an action is positively reinforced, it will happen more often, and if it is negatively reinforced (i.e., punished), it won't be. The Skinner Box is the culmination of this theory, which was used to train rats to push a lever to get food. But sometimes this device also trained rats to not push the lever by sending a shock through the floor whenever the lever was pressed.

While Skinner didn't use a Skinner Box to train the birds he would eventually use in Project Pigeon, the device he created for Project Pigeon utilized same principles of providing Operant Conditioning feedback to impact an animal's behaviors. Without his work on both, Project Pigeon might never have gotten off the ground as much as it did.

Why Were Pigeons Necessary?

Mankind has found all sorts of ways to drag innocent animals into its wars, including World War II. Soviet soldiers considered strapping explosives to dogs as anti-tank deterrents, while the U.S. thought about tying timed incendiary charges to bats in order to burn down enemy cities. Project Pigeon tried to weaponize pigeons in a similar fashion.

Believe it or not, the U.S. military didn't approach B.F. Skinner over an idea regarding pigeon-guided missiles; he came up with the idea and thought it could be advantageous. As the story goes, Skinner was mulling over weapons targeting systems when he saw a flock of birds flying in formation. Skinner was struck by inspiration. He suddenly viewed pigeons as "'devices' with excellent vision and extraordinary maneuverability."

In the 1940s, the U.S. Navy was ill-equipped to counter German battleships — American guidance systems were far too large and imprecise. Skinner saw his plan to steer missiles with pigeons as a solution as well as an evolution of humanity's reliance on the animal kingdom's superior senses. To him, pigeons could accurately steer missiles with their advanced eyesight, but he also so them as more expendable than human soldiers. This mindset, while highly controversial, would explain why Skinner designed his device without an escape hatch, thus guaranteeing pigeon pilots went up in flames along with whatever they hit.

This Targeting System Is For the Birds

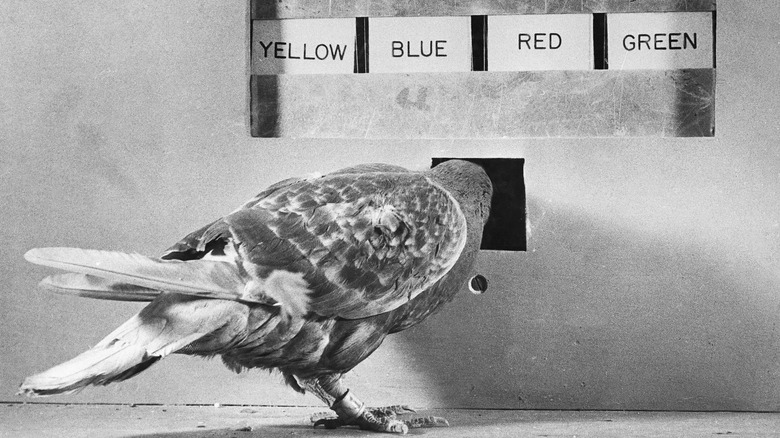

Since pigeons aren't exactly known for their eye-hand coordination — lacking hands — they couldn't pilot missiles the way humans pilot planes. So B. F. Skinner designed Project Pigeon's central apparatus around an ability pigeons display on a daily basis: pecking the heck out of stuff.

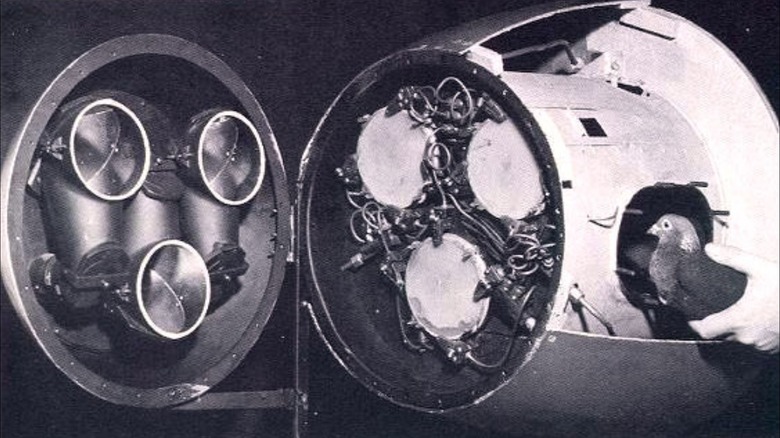

Project Pigeon revolved around a pigeon-sized cockpit Skinner dubbed the "Pelican" that sat at the front of the missile. This nose cone didn't have a Pelican beak, but the design necessity reminded Skinner of an adage about pelicans, specifically that they are birds "whose beak can hold more than its belly can," hence the name.

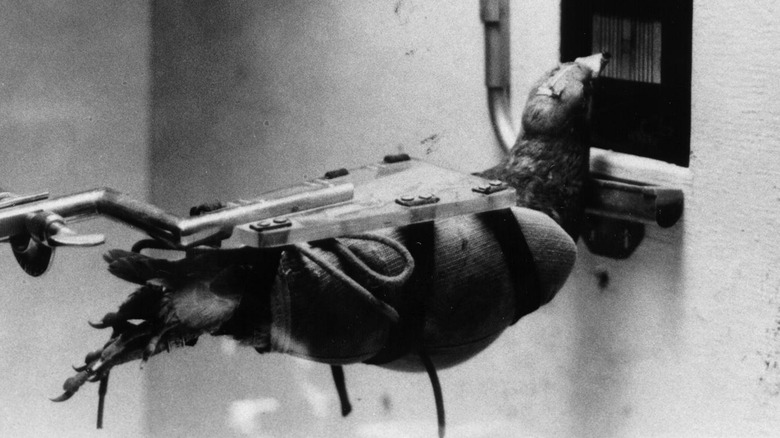

Whenever a pigeon was placed inside the Pelican, it was strapped in place and pecked at a screen that projected an image, specifically the target the missile was supposed to hit. As the pigeon pecked, cables attached to its head would help direct the missile. If the pigeon pecked at the center of the screen, the missile would fly straight, and if it didn't, the cables would send signals that altered missile trajectory until the pigeon started pecking at the image's center.

As Skinner continued Project Pigeon, he eventually learned that three pigeons were better than one. If a pigeon paused for only a second or made a mistake, a missile could fly dangerously off course, so giving it two co-pilots and making it so the Pelican sent a "net signal" produced by all three helped prevent these potentially costly errors.

How To Train Your Kamikaze Pigeon

In order to take advantage of Operant Conditioning, you need to use it to train your test subjects. Pigeons might be smart, but even they can't tell the difference between a Bismarck or a Deutschland-class battleship without the proper training — let alone know to aim for one.

At the beginning of Project Pigeon, B.F. Skinner bought 40 homing pigeons and 24 normal pigeons from a poultry store and encouraged them to peck at specific images. Whenever they successfully completed the task, they earned a bit of grain, which made them associate pecking targets with food — that's how Operant Conditioning works, after all. Through his testing, Skinner learned that pigeons responded particularly well to hemp seed, which became the main Operant Conditioning reward.

To simulate a mission, Skinner worked with University of Minnesota students to create a moving hoist that pushed the Pelican module towards images. After enough training, pigeons were able to hit any target no matter how far away it was. And as Project Pigeon continued, Skinner's tests and mechanisms evolved. After the Pearl Harbor attack, a new hoist implemented rotation to simulate more movements missiles might experience in flight, and Skinner also tested pigeons to see if they could maintain control when exposed to loud noises, extreme G-forces, or changes in pressure or temperature. But no matter what variables Skinner threw at his pigeons, their aim was true and their concentration unflappable.

Rejection Is The First Step Towards Acceptance

Since B.F. Skinner founded Project Pigeon, he had to win over military officials with his pigeon-powered pitch. To say he waged an uphill battle would be an understatement.

Skinner worked at the University of Minnesota when he came up with Project Pigeon, but what he lacked in military experience he made up for in connections. His first go of the Pelican was shown to the Dean of the Graduate School, John Tate, who showed it to one R. C. Tolman, one of the "scientists engaged in early defense activities." However, military personnel weren't interested in Project Pigeon and said Skinner's idea "did not warrant further development at the time." That was only his first rejection, though.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Skinner revived Project Pigeon and continued to demonstrate his Pelican and its pigeon pilots. Thanks to the connections Skinner formed during his first attempt, he was able to send out demo reels and provide live demonstrations, and each time, his feathered pupils performed flawlessly. However, military brass didn't take Skinner seriously until June of 1943, when the Office of Scientific Research and Development gave Skinner a $25,000 grant to further develop Project Pigeon. Technically the organization gave General Mills the money, but since the company was helping Skinner with his Project Pigeon research and development, he got to use the money to develop pigeon-guided missiles.

Until You Are Rejected For Good, That Is

After B. F. Skinner received a big break in the form of a $25,000 grant, one might assume he was in the clear. Upon looking back on Project Pigeon and its fate, Skinner stated, "Reality was no match for mathematics."

Several months after receiving the grant, Skinner and his coworkers were given one final chance. They had to convince top scientists that a bunch of pigeons could control a missile. To do so, Skinner provided a live demonstration that consisted of a trained bird, a test Pelican unit, and a target. And to drive the point home, Skinner and crew illuminated the Pelican screen with so much light the target was barely visible. Plus, observers were allowed to inject their own test conditions — many of which would have been unlikely in a mass produced Pelican cockpit — into the demonstration. Not like these issues bothered the pigeon, though. In Skinner's own words, the bird gave a "perfect performance," but his audience didn't see things that way.

The message Skinner received sometime after the demonstration was the opposite of what he wanted: "Further prosecution of this project would seriously delay others which in the minds of the Division would have more immediate promise of combat application." While he didn't know it at the time, Skinner would eventually conclude that the rival project with "more immediate promise of combat application" was the atomic bomb.

You Can't Keep a Good Pigeon Down

While Project Pigeon officially died in 1944, it lived on in spirit for quite a while longer. Even though one branch of the U.S. military wasn't interested in B. F. Skinner's proposal, other branches saw potential.

In 1948, the U.S. Navy approached Skinner to revive Project Pigeon. This new iteration, dubbed Project Orcon (short for "organic control") tested pigeons with even more advanced technology. Instead of controlling missiles with pulleys attached to pigeon heads, this time Skinner used semiconducting surfaces and gold electrodes attached to pigeon beaks. While the rehashed idea to shove pigeons into missiles was shelved in 1953, the work Skinner performed helped pave the way for the Navy's "Pick-off Display Converters," which let radar operators report on radar blips by just tapping their screens.

Even when Skinner had to give up on using pigeons to maneuver missiles, he never gave up on using pigeons period. Skinner kept many of the birds from the projects and retested them every so often. Even six years after Project Pigeon ended, his test subjects retained all of their training and accuracy. Moreover, Skinner used what he learned to develop more teaching machines. In 1954, he built a device meant to teach young students arithmetic, and in 1957, he followed that up with a machine meant to teach Harvard students natural sciences.