Here's How Astronauts Could Fight Muscle Loss Using Electric Stimulation

When you imagine traveling to space, surely one of the most fun and exciting parts — other than taking in the views, of course — would be playing in microgravity. In environments like the International Space Station (ISS), the gravity is so minimal that it's negligible, so astronauts float and can twist and turn while suspended in the air. It looks tremendously fun, and many astronauts report that they have a great time, but it's not without consequences.

One of the biggest issues to impact human health in space is muscle atrophy. Normally, on Earth, your muscles are constantly working — not only when you're walking or exercising, but even when you're stationary, as they have to work to keep you upright against the force of gravity. In microgravity environments, muscles aren't doing that work. And because muscles require constant use to be maintained, astronauts can very quickly lose muscle mass when they spend time in space.

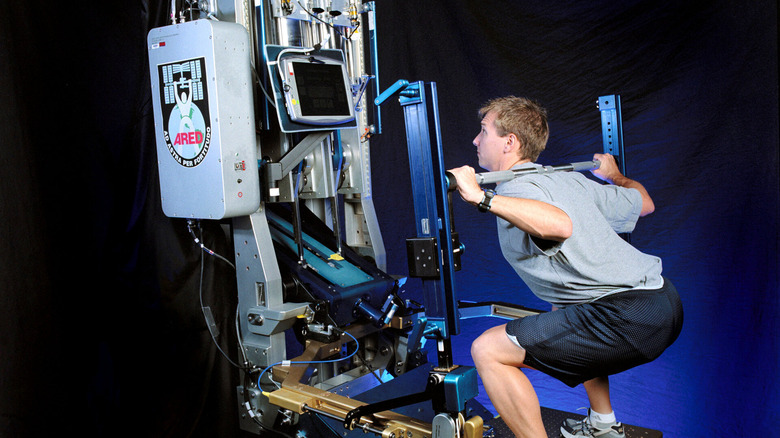

To counteract this, astronauts on the ISS spend up to several hours each day exercising, using machines like the ARED, or Advanced Resistive Exercise Device. It uses vacuum cylinders to create force, which the astronauts can then push against when performing exercises such as squats and deadlifts, helping them to keep their muscles in use even without gravity.

Machines like ARED help to keep ISS astronauts healthy, but they are time-consuming to use in addition to being bulky, taking up a lot of room. So researchers are looking for other ways for astronauts to fight off muscle atrophy.

Using electric muscle stimulation

The European Space Agency (ESA) is planning to test a method called electrical stimulation on the ISS. This works by applying controlled electric currents to astronauts' muscles, such as those in the legs. Pads are stuck to the skin which deliver the currents. Afterwards, the muscle mass and the astronauts' strength are checked to see how they recover.

The researchers also plan to use methods like MRI scans, microcirculation analysis, and blood samples to check on astronauts' health and see if the muscle stimulation is having an effect.

The hope is that such methods could be a more efficient way for astronauts to avoid muscle atrophy than having to take several hours out of their days to perform exercises. It is also important for longer planned future trips, like crewed missions to Mars, which would require astronauts to be in space for more than a year at a time.

The research could even be helpful for people on Earth as well. "If this is proven successful, this particular technique will not only contribute to the well-being of astronauts while they're in space and exploring further and further beyond our planet, but it also is going to improve ground applications, such as benefiting the elderly people in critical conditions and even athletes," Kristen McDonell, the Research and Payloads Group Leader at ESA, explains in a video.