Time-Tested Tech: 10 Perfect Examples Of 'If It Isn't Broke, Don't Fix It'

Depending on how you choose to define "tech," there's a good chance you see or use things every day that were conceived hundreds, or even thousands, of years ago. But if it seems disingenuous to call bricks or the comb "tech," there are still endless examples of devices and methods that are sub-par by modern standards but still do the job.

Ancient technology can survive for any number of reasons. If a hardware or software solution is suitable for its purpose and stable, sometimes there's simply no percentage in fooling around with it. Why rock a boat that's bobbing along just fine? And sometimes better solutions are possible, and perhaps even easy, but there's a limited market for them. Without much potential return on investment and public funding or visionary investment à la SpaceX, it's simply not practical to update and improve.

Another big reason old systems stay in place is security. Many systems that pre-date the Internet or even networking are kept around just because their isolation protects them from attack. And if there's enough investment in an old solution out there in the world, completely replacing it with a new solution is practically impossible. Consider the slotted screwdriver, a grotesquely inferior technology so entrenched it might never die in certain industries, like the electrician trade. There are simply too many slotted drivers in too many toolbelts.

IMAX runs on a Palm Pilot

When eagle-eyed users noticed the PalmOne m130 on a tablet screen in a TikTok video about the film "Oppenheimer," they opened the door to one of the least dramatic and least surprising examples of old tech still serving well today. And the example turned out to be an instructive one. What TiKTok users saw was an emulated PalmOS device running on a Windows tablet. It turns out that IMAX's quick turn reel unit (QTRU) has long been managed by a piece of software running on the 2002 PDA. Here is a story about old tech that was so suitable that new tech was devised to keep it alive.

The Palm's duties are critical but don't require much or any interaction from the projectionist. It displays the feed and takeup status of two projectors and indicates when all is well, but otherwise, it controls the QTRU without user intervention. Rather than reinventing a perfectly good reel, IMAX kept using the Palm program but has switched to an emulated Palm device... presumably because Palm has been out of business since 2011.

Critics might question the wisdom of developing a platform to emulate a Palm Pilot, given the risks involved. Emulation is almost always imperfect, and platter operation and switching in a live theater environment is not the place to discover bugs. But consider the alternative — a long development and testing process introducing a bunch of risk to a system that's been working perfectly for a decade or more.

Old nuclear weapons work as long as we don't use them

"Oppenheimer" isn't the only nuclear wonder sitting atop extraordinarily old tech. Much of the U.S.'s nuclear weapons arsenal relies on very old technology that has been in use for half a century. But if the fate of a film turns on IMAX's platters, the fate of the world relies on a pretty dicey process for keeping nuclear weapons working smoothly.

These systems have, fortunately, remained mostly unused for decades. This becomes a particular problem because much of the weapons stockpile depends on tech well beyond its intended service life. The Minuteman III, for example, was supposed to have been retired in 1980. And the B52, slated to end its service life in 1982, will be used beyond 2050.

It has proven challenging to sustain hardware not designed to be maintained this long. For example, the Ohio-class nuclear submarines have experienced failure of parts that were not designed or intended to be replaced, leading to technical and supply-chain complications. A 2020 report to the National Nuclear Security Administration (via the Federation of American Scientists) warns, "A goal of reliable performance after 40–60 years of unmonitored storage poses difficult, and perhaps unrealistic, challenges for electronic components to electrical subsystems and systems..."

But the Nuclear Threat Initiative warns that modernizing these systems, while essential, introduces inevitable "cybersecurity and AI safety" risks. These modernizations will also be extremely costly and under a lot of schedule pressure, which might lead to reduced capabilities of the arsenal.

Nuclear reactors might get better with age

Of course, systems that aren't used sometimes present different challenges than ones that are constantly in use. Like their layabout missile cousins, nuclear reactors have reached that age at which impertinent youngsters start to refer to it as "aging." Nuclear power generates almost one-fifth of U.S. electricity, over 770 billion kilowatt-hours as of 2020. Much of the equipment used to run nuclear facilities was put into service in the 1970s and 1980s, and some of it had a 40-year licensing period, the default for power control technologies at the time.

In a paper about modernizing nuclear power plant instrumentation and control, the International Atomic Energy Agency argues that extending the lifecycle of aging nuclear power control systems reduces safety and increases costs, showing that while these strategies delay the point at which the systems become unreliable, there are some challenges. Replacing the old systems, for example, requires identifying the right strategy; maintaining capabilities and safety margins; integrating old systems with new ones; guaranteeing software integrity; training personnel; and addressing security issues raised by the process.

But the Breakthrough Institute makes an interesting point about aging: Can you call a population "old" when none of its members have died? Fortunately, that describes the U.S. nuclear power infrastructure — various components are long in the tooth but show no sign of slowing down. And because parts of systems have been well-maintained, they often function better today than they did originally.

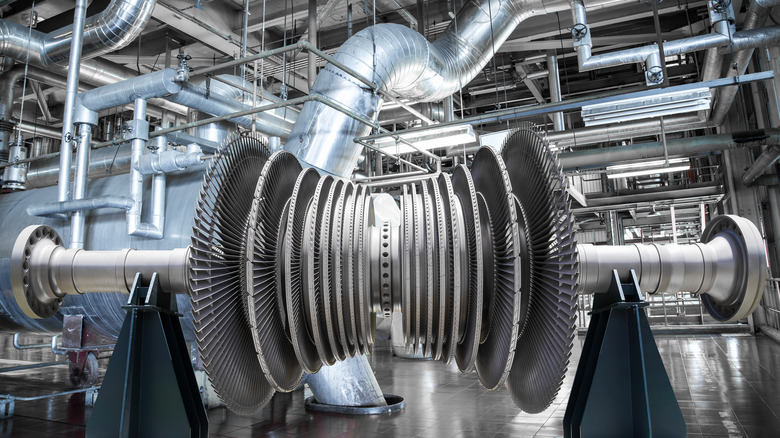

Steam turbines still generate electricity... almost all of it

Of course, any power system that supplies the public at large is going to be a huge operation. And huge operations are naturally more resistant to unnecessary change than smaller, less consequential ones. That's true of nuclear energy, which supplies 18.2% of U.S. electricity, and it's true of power created with steam turbines, which are involved with 88% of the country's electricity generation. (If the math is bugging you, note that nuclear power creates electricity via the intermediate step of steam turbines.)

This means that almost 9/10th of U.S. electric power is generated by a device invented in 1884 that involves shooting steam through some glorified fan blades. For some context, 1884 was the year Alaska became a U.S. territory, "Huckleberry Finn" was written, and the Washington Monument was completed.

Like nuclear reactors, steam turbines are surrounded by support and control mechanisms that do advance, sometimes rapidly. But the basic underlying tech is essentially unchanged. The tech is reliable, and many improvements and efficiencies can be introduced through all of those secondary systems, so there's little reason to seek an alternative. Although, there has been some meaningful progress toward a clean energy and solar power storage solution based on the steam turbine.

The Colt model 1911 might live forever

You expect a massive weapons system like the U.S. nuclear arsenal, like giant things everywhere, to be constitutionally averse to change. And you might expect that small personal weaponry would be correspondingly more likely to adapt and adopt new technology and designs. But the Colt model 1911 is the story of a handgun design so successful it hasn't needed any substantial updating in over a century. Not only do many new handguns use features first designed by John Browning, but many owners still use their original Colt 1911s.

The 1911 tells the story of old and new tech in two interesting ways. First, it was designed as a well-conceived replacement for the Colt M1892, the official Army sidearm at the time. The 1911 used .45-caliber ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) rounds, also invented by Browning to replace the M1892's less effective .38-caliber rounds. So this was a case in which an established technology with a huge and expensive installed user base was discarded in favor of a better mousetrap.

When Browning later designed his Hi-Power pistol, he had to navigate the engineering without violating any of his own 1911 patents, which he no longer owned. Yet the Hi-Power was also enormously successful, eventually used by 93 armies and police forces worldwide and showing that a successful solution like the Colt 1911 can easily survive challenges from other, arguably better alternatives. Incidentally, Browning also designed the M2 machine gun, which is still in use by the U.S. Army today.

MOCAS handles $1.3 trillion in transactions

Its very name, Mechanization of Contract Administration Services (MOCAS), hints at its age and institutional scope. First put into commission in 1958, this COBOL-based software has been used to manage contracts for the U.S. Department of Defense via an IBM 2098 model E-10 mainframe. But the software is the star of this particular antique show. MOCAS was originally built as part of a cutting-edge solution using the latest mainframe hardware and COBOL, which was so bleeding-edge it hadn't even been invented yet. (MOCAS was likely originally programmed using the Flow-Matic language, a direct ancestor of COBOL.)

MOCAS started life as a powerhouse, but it's still in use today because of its stability and reliability (and institutional inertia. The scope of the undertaking and its associated costs and long schedules stall any progress toward replacing MOCAS). The IBM mainframe it runs on can execute less than half the instructions a modern $3 microprocessor like the ESP8266 can manage in one second, and it has about as much RAM as a mid-range Raspberry Pi.

As of 2015, the system managed 340,000 contracts with transactions worth $1.3 trillion — that contract number is far within the range of, for example, the Jet database engine Microsoft Access uses. No longer a military-industrial technical marvel, MOCAS is just a system that works well and is still extensible enough to keep things flowing well with new interfaces, various I/O changes, and other improvements over the years. The system's last major technical revision was in the 1980s.

AM radio is not just a bunch of talk

More than 82 million Americans aged 12 and up listen to AM radio every month. AM Radio was invented in 1906, became widespread in the 1920s, and somehow is still used by 30.9% of American radio users. Over 6,000 stations in the U.S. deliver AM broadcasts, mostly focused on spoken word formats like news, politics, sports, weather, and traffic. AM radio is prone to interference and is generally of lower quality than FM, which is why it's not preferred for music listening. With a daytime range of about 100 miles and a much longer nighttime range, listening to distant AM stations remains a hobby among enthusiasts.

AM radio's reach is surprising. In fact, to media consumers accustomed to streaming audio, the whole concept of synchronous radio with ads and a handful of channels might seem bizarre. But Nielsen's 2023 Audio Today report shows that AM/FM radio is competitive with all other media sources, including television and smartphones. In fact, radio outperforms all audio services in terms of reach and dominates drive-time listening. An American away from home is most likely to be listening to the radio.

Nielsen's data is oriented toward market researchers, but much of it leads back to one key fact about radio listeners. They are working people who commute for a substantial amount of time, and either because of content or convenience, prefer radio to streaming options. So it's unlikely that AM radio will go away any time soon.

Fax machines keep giving

Sometimes outdated tech soldiers on propped up by inertia, incompetence, and incompatibility in their many forms. So it is with the fax machine. If you were surprised that five times as many people listen to AM radio as watch the NBA finals, you might be downright shocked that 7% of U.S. households have a fax line. According to Gitnux Market Data, there were 17 million fax machines in service in the U.S. and nine billion faxes sent each year throughout the world.

Healthcare remains responsible for about three-quarters of faxes sent in the U.S., with around 70% of hospitals sometimes relying on fax to transmit health records as of 2019, and about 13% of hospitals using only electronic technology to transmit health records (via the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology). When electronic health records (EHR) aren't interoperable between healthcare facilities, fax machines step in with near-perfect reliability.

Whatever one's opinions about fax technology, there's no question that it works. That is, at least in terms of reliability and security, it isn't broken. While it's been "fixed" for a while by competing technologies, it continues to serve certain segments well enough to keep their trust.

Hard Disk Drives keep spinning

Like so many tech obituaries, the reports of the spinning disk hard drive's death are greatly exaggerated... so far. Despite their reputation, spinning drives still have crucial advantages over solid-state flash drives (SSDs). For the youngest generation of computer users, raised on flash drives in their various forms, HDDs must seem only slightly more plausible than the Commodore 64 cassette tape drive. Fragile spinning magnetic platters with a read/write head make microscopic changes at a blazing rate. But not nearly as microscopically or as fast as an SSD can write the same data.

But the spinning HDD does have some advantages over flash storage. You can write and re-write data to an HDD a practically unlimited number of times. SSDs, on the other hand, have the rather severe problem of becoming unreliable after a few million write cycles. This poses a serious problem for people who keep their disks nearly full, forcing constant writes to the same areas of the SSD.

The size of the SSD is effectively reduced over time, and HDDs don't suffer from this issue. And spinning hard disks are comparatively cheap, traditionally as little as one-fifth the price of flash memory (though price parity is likely just around the corner). And they might be comparatively slow, but HDDs are fast enough for most ordinary uses, and RAM caching improves their apparent performance to near-SSD levels for commonly used files.

Postal vehicles deliver

Whatever you expect when you buy a vehicle with an S-10 pickup's chassis, the powerplant of the mid-engine Fiero, and manufactured by the aerospace giants responsible for the F-14 Tomcat, it might not be the humble Postal Service LLV. The USPS delivered 127.3 billion pieces of mail in 2022, possibly on behalf of people who aren't quite ready for the fax machine.

Most of that mail was delivered by the 99,150 Long-Life Vehicles, the familiar mail trucks designed by Grumman and produced between 1986 and 1994. Sure, that's less impressive than the longevity of a 1958 computer program, but keep in mind that the average lifespan for light vehicles just hit a new record in the U.S. at 12.1 years.

The LLVs were built to demanding specs, and as you might expect, Grumman delivered. This turns out to have been a much better use of the Fiero's "Iron Duke" engine, and with a few tweaks, the mail trucks have served admirably ever since.

But, as the saying goes, nothing except a nuclear reactor lasts forever. The USPS announced in December 2022 that it would replace the LLVs with purpose-built electric vehicles and off-the-shelf Ford EVs. If you've gotten used to the homely LLV, prepare yourself to get accustomed to the downright peculiar Next Generation Delivery Vehicle (NGDV). There's no way to know if you'll see them on the road as long as the LLVs have been, but you'll certainly notice when you do see one.