AD-1: The Strange NASA Aircraft With A Pivoting Wing

You might have noticed that the wings of unpowered gliders look very different from fighter jets. That's because they're optimized for completely different modes of flight. Long, straight wings are ideal for fuel efficiency and controllability at slow speeds, while swept or "delta" type wings are best for high-speed flight. Designing a wing that can perform efficiently at both low and high speeds is one of the most difficult challenges in aeronautics.

As early as the mid-1940s, German designers working on early fighter jets realized that a swept wing was the most efficient design for high-speed flight but found that it created problems in the slow-speed envelope — the initial phases of flight and when landing. The Messerschmitt 262, the world's first operational swept-wing fighter, was the fastest plane in the sky in optimal conditions, but it was inefficient and lacked maneuverability at slower speeds.

Postwar, airplane designers continued to grapple with the problem. We're all familiar with one solution: The variable-incidence "swing-wing," made famous by the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, star of the 1986 movie Top Gun. The F-14 was a superb multirole fighter, but there are several reasons why its wing design wasn't more widely adopted. Swing-wing mechanisms are heavy, highly complex, and very maintenance-intensive. As the wings sweep forwards and back, the airplanes' center of gravity changes, requiring constant correction by advanced fly-by-wire systems. But there's more than one way to move a wing. Rather than swinging, what if the wing could pivot?

The NASA AD-1

The NASA AD-1 was the spiritual successor to unflown wartime designs from German aircraft manufacturers Blohm & Voss and Messerschmitt for aircraft whose wings could be rotated in flight around a central pivot. The AD-1 was built by NASA in the late 1970s as a test airframe after NASA aeronautical engineer Robert T. Jones became interested in the concept of an "oblique" wing. Once considered outlandish, wind tunnel tests showed that such a wing design had the potential to greatly improve the fuel efficiency of large, supersonic transport-type aircraft.

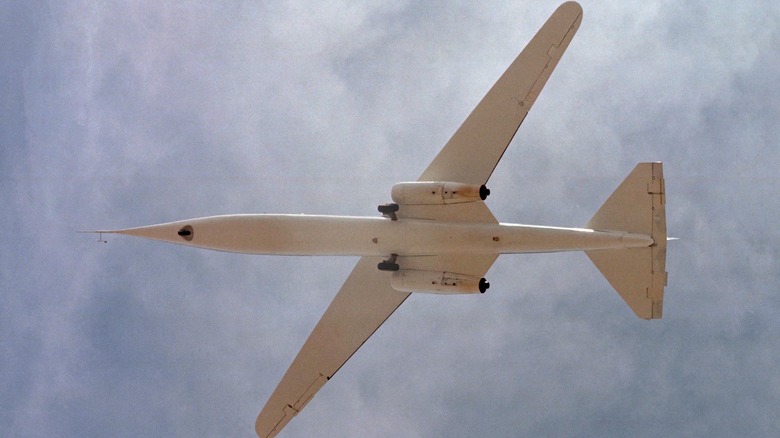

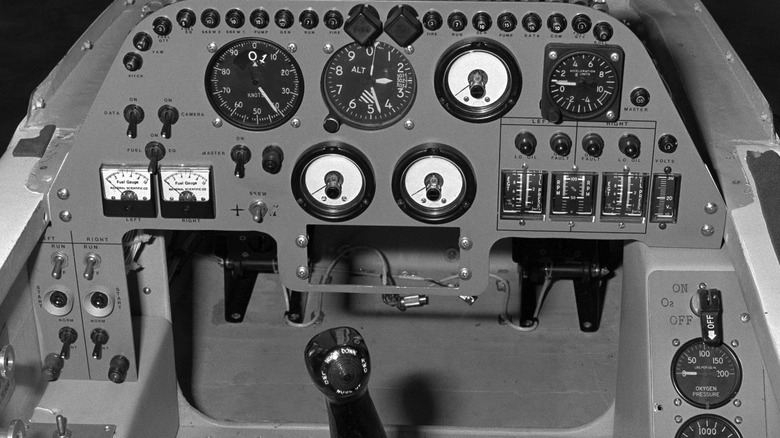

Commissioned for less than a quarter of a million dollars (equivalent to a little over $1M today), The AD-1 was intended as a simple, low-cost demonstrator of the oblique wing concept. Designed by maverick airplane designer Burt Rutan, the small, squat AD-1 looked more like a kit plane than an experimental aircraft. It weighed under 1,500 pounds and lacked any hydraulics. Its twin turbojet engines could propel it to a top speed of only around 200 miles per hour.

The wing of the AD-1 would be perpendicular to the fuselage for maximum lift and controllability at low speeds and during takeoff and landing. At high cruising speeds, where a perfectly perpendicular wing would create unwanted drag, the wing could be rotated clockwise so that the righthand leading edge came forward, and the left moved backward. This "slewed" configuration resulted in lower drag in the cruise phase of flight and higher fuel efficiency. It also looked very odd indeed.

AD-1 Flight Testing and Legacy

Over 18 months, NASA test pilots flew the AD-1 79 times, moving the wing in increments until a maximum angle of 60 degrees was achieved. Test pilots reported that the AD-1 had generally good handling qualities at wing sweep angles up to 50 degrees, but after that, its inexpensive fiberglass structure and unsophisticated flight control system meant that it became hard to control. Computerized flight controls and a more rigid wing might have solved these issues, but they were out of budget.

For safety, the bargain-basement AD-1 was limited to a maximum speed of 170mph, but even with its restricted performance envelope, information gleaned from test flights successfully demonstrated the validity of the oblique wing concept more than 30 years after it had first been proposed. During the program, both Boeing and Lockheed conducted design studies on supersonic passenger planes with oblique wing designs. One such proposal, by Boeing, described an airliner that could carry 190 passengers at a sustained cruising speed of Mach 1.2.

Sadly, we never got to fly on a supersonic, fuel-efficient, oblique-wing airliner because a successor to the AD-1 that could have proved the concept for good was never developed. Although NASA continued to tinker with the idea of slewed wings into the 1990s, modern research into high-efficiency airframes has moved on and is now focused on "blended wing" designs. After testing was completed in 1982, the one and only AD-1 was retired to the Hiller Aviation Museum in California.