5 Of The Strangest Cars To Ever Race In The Indy 500

The Indianapolis 500, better known as the Indy 500, is one of the most long-standing auto race events in American history, with tradition going back over 100 years. That's really the name of the game, tradition: from the style of cars being driven to the Brickyard track where the race is held every year, right down to the mysterious bottle of milk on the victory lane.

While the race is deeply steeped in tradition, that does not mean tradition dominates every aspect of it. Over the past century of Indy 500 races, brave (and, possibly, slightly mad) engineers have experimented with the idea of the classic open-wheeled racer, breaking the mold in new and interesting ways.

Granted, most of these ideas didn't work, but we still have to commemorate the adventurous spirit that goes into making an off-kilter vehicle, then strapping yourself into it and driving it at high speed.

The Eagle Aircraft Flyer Special

When you were a kid doodling in your notebook, what was your first idea for making a fast, cool car? It was probably to make it less like a car, and more like an airplane, right? Good, now you're in the headspace of Eagle Aircraft Company founder Dean Wilson, who wanted to make an IndyCar in the image of his favorite aviation projects.

Enter the 1982 Flyer Special, also known as the "Cropduster." This vehicle shirked all of the established norms of IndyCars, placing the driver at the front instead of the back, strapping on fins and wings, and packing a construction of balsa, aluminum, and steel tubes.

If this vehicle were a plane, it probably would've worked great, but as a car, the Flyer Special unfortunately couldn't keep up with vehicles that were actually designed with a racetrack in mind. It couldn't qualify for the Indy proper, and the design was scrapped.

The Capsule Car

Over the course of the Indy 500's history, several cars have employed a multi-seat design, placing the driver in something akin to a motorcycle sidecar to leave room for stronger engines and additional gimmicks in the main body. Automotive engineer Smokey Yunick, who had a good career in designing NASCAR racers from the '50s to the '70s, wanted to take this concept to its natural conclusion. Yunick wanted to pack the main body with as much muscle as he could get away with, which meant sticking the driver in a little side car.

Yunick's '64 Capsule Car placed the driver in the titular capsule: a sidecar mounted between the left wheels, while the main fuselage of the vehicle packed a powerful engine fed by a large-capacity fuel tank. The capsule was side-mounted in order to keep the vehicle balanced as it consumed its massive fuel supply, though it wasn't quite balanced enough. Due to a wall brush during the last qualifiers, the car couldn't enter the race proper.

The Sumar Streamliner

One of the dominating concepts of most IndyCars is aerodynamics. Your engine can only be so powerful, after all, so you needed to employ every additional trick and gimmick you could to maximize your vehicle's potential speed, and the first trick in the book was minimizing the profile. One car that raced in 1955 went all-in on the aerodynamics bandwagon: the Sumar Streamliner.

Rather than the usual open seat employed by Indycars, the Streamliner enclosed its driver in a bubble shell, while the body featured sloping curves designed to reduce wind resistance as much as realistically possible. Ironically, this sloped body actually made the car drag more, but after some modifications, it was able to reach speeds of over 139 MPH.

The main problem was in the driver's seat — specifically, driver Jimmy Daywalt felt extremely cramped and nervous in the enclosed shell, not to mention concerned that he couldn't see the car's front wheels. He made it through okay, but he called it one of the most difficult vehicles he ever had to drive.

The STP Paxton Turbocar

In the 1960s, jet engine technology was the new kid on the block, carrying passenger planes to new heights. Naturally, some automotive engineers got the idea in their heads to try building a jet-powered car. After all, something strong enough to make a plane fly would surely send a car screaming down the track.

Several cars tried this concept with little success throughout the '60s, but there was one that almost got it right: the STP Paxton Turbocar. With the raw muscle of an ST6 turbine, this rocket ride was certainly capable of some intense speed. However, the rub was getting the vehicle to safely handle that kind of power.

The initial debut of the Turbocar had to be delayed because the heat from the turbine was warping the frame, and even when it finally hit the track in '67, one of its bearings broke, prompting officials to disqualify the car and ban turbines from the race indefinitely. It's a shame, as before that bearing broke, the Turbocar was on track for first place.

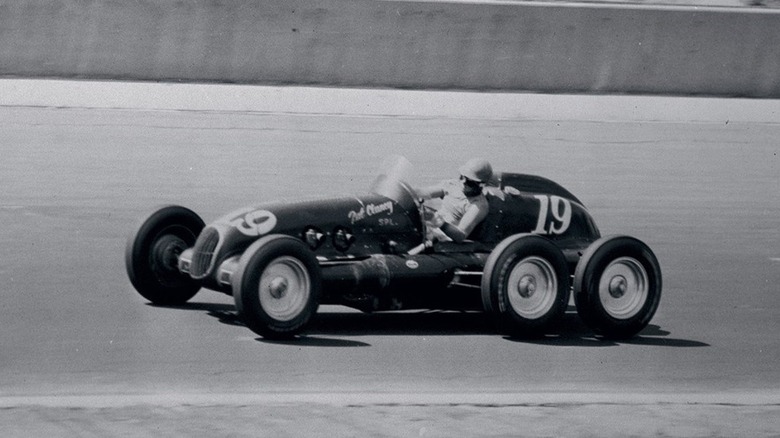

The Pat Clancy Special

When you're trying to create the best race car of all time, the train of thought usually goes in one of two directions: either you make it faster, or you make it handle better. While the vast majority of experimental racers took things in the former direction, exactly one engineer opted for the latter path in the entire history of the Indy 500. That engineer was A.J. Bowen, who created the race's first and only six-wheeler — the 1948 Pat Clancy Special, named after his team's owner.

The Pat Clancy Special featured a Kurtis-style chassis with six magnesium wheels; two in the front, and four in the back. The two axels of the four rear wheels were connected by one joint, giving the car a much more literal interpretation of "four-wheel drive."

With the power of its wheels, the Pat Clancy Special could fly like a dart when driving in a straight line, but ironically, it couldn't handle tight turns very well. In spite of itself, the vehicle did manage to make it to the Indy proper, though it was converted to a normal four-wheeler afterward.