How Astronomers Are Searching For Hidden Supermassive Black Holes

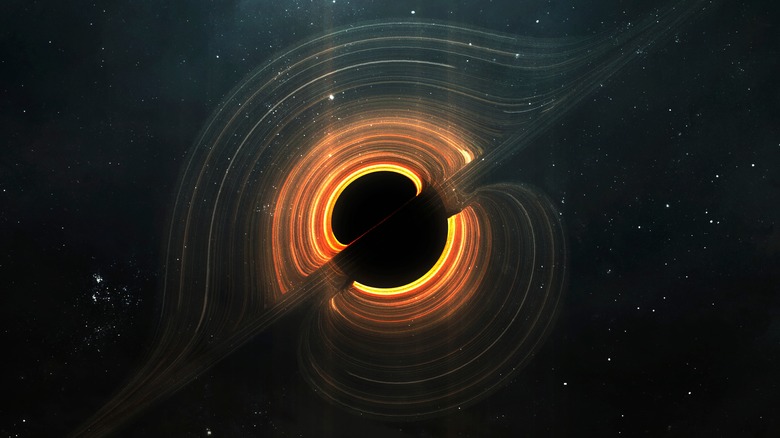

How do you look for something that absorbs light? That's the challenge for astronomers who want to study black holes. While black holes are themselves invisible, as their enormous gravity sucks in anything which gets too close, even light, they are usually visible because they are surrounded by clouds of glowing gas. As the gas swirls around them, it rubs together and heats up due to friction, making it warm enough to be seen from far away.

However, not all black holes are active, meaning only some of them are pulling in material from around them. Other black holes are passive, merely sitting alone in the darkness of space, which makes them almost invisible as there is no cloud of warm material around them. Yet other types of black holes are shrouded by dust and gas which makes them hard for us to see. Astronomers are searching for these hidden black holes using innovative methods, such as using NASA's Chandra X-Ray Observatory to look for their signatures in the X-ray wavelength.

By combining data from the Chandra Source Catalog, a list of X-ray sources compiled over the first 15 years of the observatory's operations, along with visible light data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, they have been able to identify hundreds of black holes which were unknown before. "Astronomers have already identified huge numbers of black holes, but many remain elusive," said the lead researcher of the project, Dong-Woo Kim of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA). "Our research has uncovered a missing population and helped us understand how they are behaving."

How astronomers spot invisible black holes

To find the hidden black holes, the researchers focused on supermassive black holes. These are a particularly large type of black hole that are found most often at the centers of galaxies. It is thought that almost all large galaxies have a supermassive black hole, but some of these have yet to be observed. In this project, the researchers compared galaxies that were bright X-ray sources but dim in visible light, which are called "XBONGs" (X-ray bright, optically normal galaxies). They were able to identify 817 of these XBONGs that shone brightly in Chandra's X-ray data but not in the Sloan survey data.

When they looked at these XBONGs, they found that around half of them were glowing in the X-ray wavelength due to previously undetected supermassive black holes. These black holes were busy feeding on nearby material, so they were giving off radiation, but most of that energy in the visible light wavelengths was hidden by thick clouds of dust and gas. X-rays can more easily pass through these shrouds, so they can be detected even when visible light can't be.

The researchers knew that they were looking at supermassive black holes and not other types of objects because the X-rays they were giving off were so bright, they must have been coming from supermassive black holes which are feeding and growing quickly. "It's not every day that you can say you discovered a black hole," said another of the researchers, Alyssa Cassity of the University of British Columbia, "so, it's very exciting to realize that we have discovered hundreds of them."