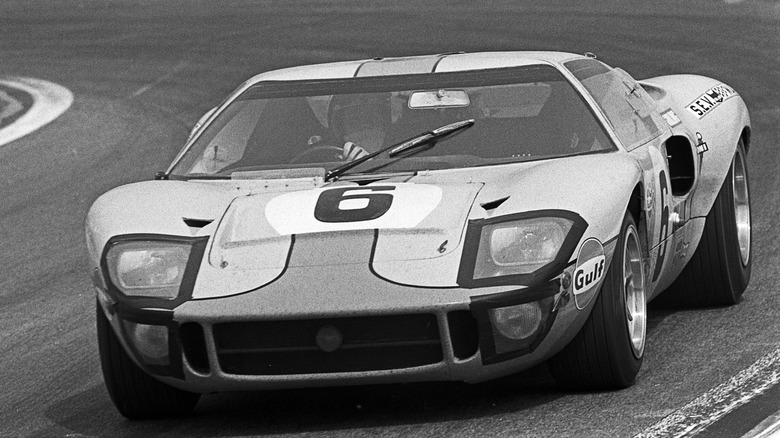

The 11 Coolest Features Of The Ford GT40

Taking Enzo Ferrari on at his own game was always going to be a gamble. Plenty had tried, and all had failed to stop the dominance of Ferrari's racing machines throughout the '50s and '60s. The car that eventually ended the reign of the Prancing Horse was not, however, one of the Italian brand's long-time rivals that, after years of competition, finally perfected its formula to gain the winning edge. It was instead an upstart team of engineers and racing drivers backed by a manufacturer that had virtually zero experience in endurance racing, competing in a car that was hastily developed and proved to be deeply unreliable at first.

That car would come to be known as the Ford GT40, and its creation and development remains one of the most remarkable feats of engineering in the history of motorsport. From its humble beginnings in a small garage in London, the GT40 would go on to claim racing's most prestigious title, the overall win at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, not once but three times. However, if it wasn't for a disagreement between its American manufacturer and Enzo Ferrari himself, the GT40 may never have existed at all.

It was built because of a grudge

Ford had decided it wanted to enter GT racing in the early '60s, and initially, the company's plan was to partner with an existing successful racing outfit. Ferrari seemed like the natural choice, as it was dominating the motorsport world at the time as well as making some of the world's greatest road cars. Ford entered a period of negotiation in an attempt to buy Enzo Ferrari's company over the following months. The idea was that Ferrari would be absorbed into Ford entirely, producing both road and race cars and giving Ford the leading edge at the world's most prestigious race events.

His company was badly in need of new investment, but Enzo Ferrari realized that by selling it, he would potentially lose his freedom to lead his outfit in the way he saw fit. He backed out of the deal, leaving Ford empty-handed after months of bargaining. Henry Ford II was infuriated and ordered that a team be assembled to build a better race car than Ferrari, entirely from scratch. Early members of the team included Roy Lunn, who had previous experience with a Le Mans program at Aston Martin, Carroll Shelby, and a handful of others.

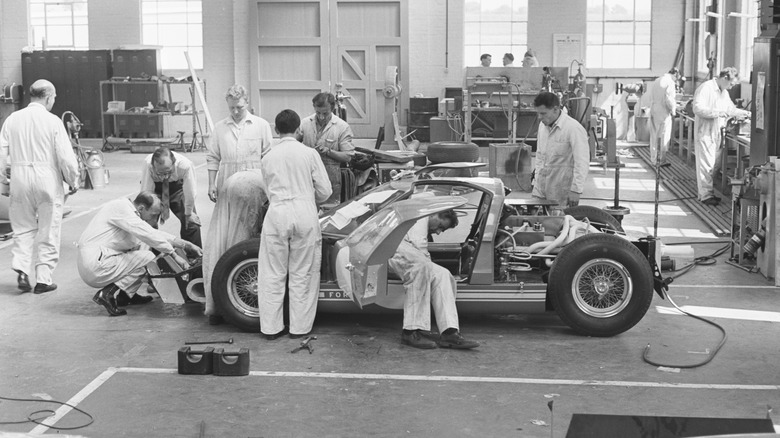

Developed in England and America

Initially, Lunn and Shelby were sent from the United States back to Lunn's native England to begin development work on the car. There, they assembled a small team including Eric Broadley, known for his work on the pioneering Lola Mk6 GT, and John Wyer, who had previously won Le Mans with Aston Martin as a race manager. The team initially set up shop in Broadley's garage in Bromley, near London, but later moved to the other side of the city, to a base in Slough.

The initial design for the GT40 was conceived and built across the two locations, but after some initial failures in competition and disagreements between Broadley and the rest of the team, the operation was moved to a new base in Michigan. Also taking a larger role Stateside was Carroll Shelby, whose Los Angeles-based Shelby American facility gave the team access to new testing grounds, new engineers, and a fresh batch of ideas.

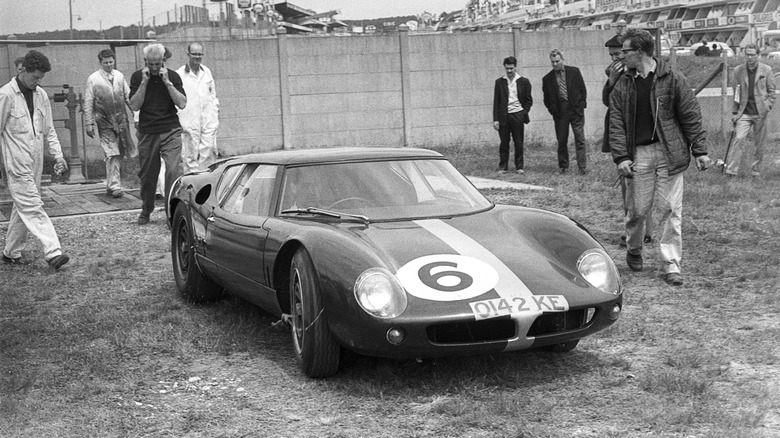

Based on a Lola chassis

While it was these new engineers that arguably gave the GT40 the competitive edge it needed to take on the Italians, the whole car would never have been possible were it not for the English underpinnings on which it was built. The Lola Mk6 GT (pictured above) was a promising prototype built by Broadley, and its design formed the basis of the GT40. However, disagreements with the team meant he left Ford to set up his own racing outfit in the summer of 1964.

While the GT40 continued development without him, Broadley's Lola quickly established itself as a major player in the racing sphere in its own right. Just two years after the split, Lola won the Indianapolis 500 and Can-Am Challenge Cup, and a year later in 1967, won the Italian Grand Prix. The T70, one of Lola's most successful cars, was actually one of the original unused designs that Broadley had proposed for the GT40. Ironically, much the same as if Ford had never fallen out with Ferrari, Lola's 50-plus years of racing success might never have been if Broadley hadn't fallen out with Ford during the GT40's early development.

The GT40 MkI was not very successful

Even if the fallout eventually spawned a new, successful racing manufacturer, the GT40's early development turmoil made it something of a disaster for the hastily-arranged team. The MkI cars had proved themselves to be fast, but it was the "endurance" side of endurance racing that proved a tougher nut to crack. Through the car's first season in 1964, it notched up a series of embarrassing DNFs, with the suspension failing at Nuremburg and the transmission giving out at Le Mans. Ford had entered three cars for the Le Mans race that year, but 12 hours in, all three of them had been forced to retire.

The rest of the season was no more successful, with a disastrous race at Nassau at the end of the year confirming that the cars simply couldn't last for an entire race, never mind challenge for the win. It was, in many ways, back to the drawing board for the team, who needed a serious change of strategy to be taken seriously as a racing outfit.

Carroll Shelby led the second development team

It was at this point that the decision was made to transfer the project Stateside, with Carroll Shelby taking charge of racing operations and Roy Lunn tasked with overseeing the team's engineering efforts. Another key player brought on board by Shelby was Ken Miles, who quickly set about tweaking the GT40 to his own liking. By accidentally resetting the suspension settings, Miles found performance increased by a significant margin, while another engineer, Phil Remington, gave the car an effective boost of 79 horsepower by changing the air ducting.

Shelby's team was given the freedom to adjust and redesign the car as much as they liked, something that Ford's executives had not been so keen to allow the English team to do. Top Gear quotes one engineer brought in for the English section of the project as saying, "There was no deviating from the script. Well, motor racing is about as far removed from that as you can get." With Shelby's team now given full permission to rewrite the script as they saw fit, the GT40 program began to evolve from a potential-filled project to a serious racing outfit.

Powered by a 7.0-liter 428 V8

Central to the American team's efforts was the replacement of the initial 289-cubic-inch V8 engine with a 7.0-liter 427-cubic-inch unit, the same engine that had already been deployed to great success in the Shelby Cobra. Fitting a much larger engine inside the compact, aerodynamically-sensitive car proved a huge challenge for Lunn and his team, but with the new powerplant squeezed into place, on-track testing could begin.

Development driver Miles immediately noticed the difference between the old engine and the new one, reportedly telling the team, "That is the car I want to drive at Le Mans this year." With the new V8, the GT40 achieved a top speed of 210 mph on Shelby's test track. However, since the 428 was fitted mere weeks before the start of the 1965 Le Mans race, the decision was made that Ford would enter two cars with the unproven 428 (known as the GT40X) alongside the existing 289-engined cars that were already over in Europe.

Improvised aero

Testing and improvements of the cars continued right up until race day, with tweaks to the spoiler and aerodynamics made as late as possible in the development process. The cars entered Le Mans with a lot of ad-hoc changes, and although the new aero package proved to be effective, the team's race was cut short by a number of critical parts failures. In particular, it was later found that a number of mistakes had been made when Lunn rebuilt the gearboxes shortly before shipping them off to France, and as a result, they failed mid-race.

The team's "trusty" 289 engines also turned out to be highly unreliable, a factor that was later blamed on the teams focusing too much on development for the Indianapolis 500, neglecting to properly test the units they were sending to Le Mans. Although the 427 car proved to be significantly faster than any Ferrari during practice, it was the problems arising from these carelessly-assembled parts that ultimately cost Ford the victory that year.

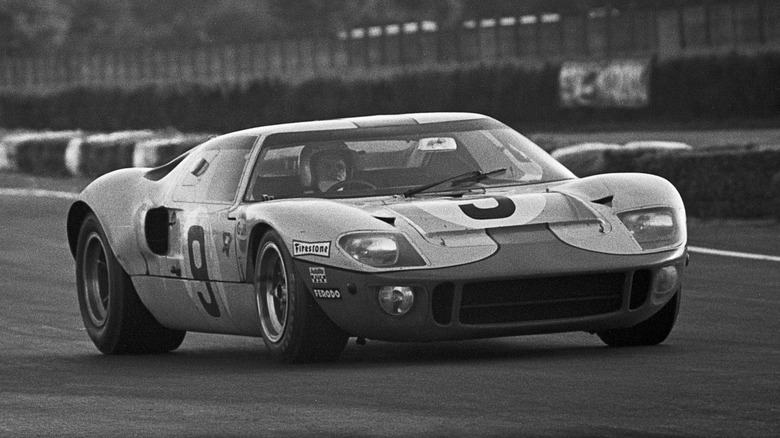

A Le Mans win in 1966

After proving that the GT40 did indeed have the pace to outrun Ferrari's best offerings, the Ford team doubled down on its bid to win the 1966 race. This time, nothing was left to chance, and the engines were thoroughly tested for a 48-hour period in race conditions to ensure that they'd be able to go the distance. Ford also brought in its NASCAR racing team Holman & Moody for extra manpower, and with a much bigger and better-prepared team, headed back to La Sarthe for the 1966 running of Le Mans.

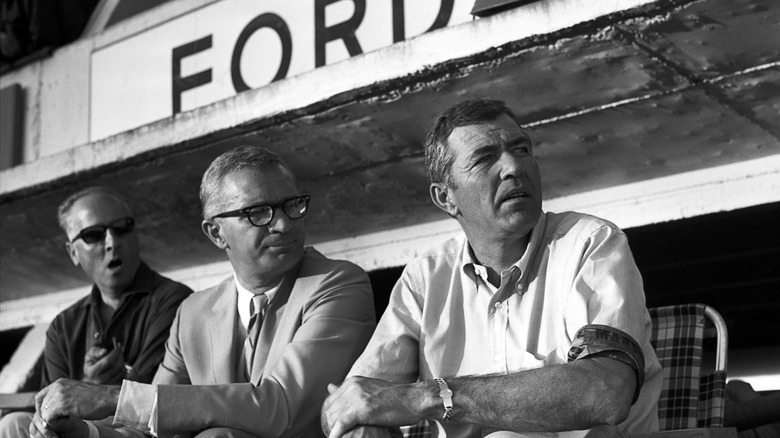

This time, the Ferraris were quickly ruled out of the competition due to mechanical failure, the same fate that had beset the Ford team the year before. But, most of the GT40s remained on track, eventually taking a commanding 1-2-3 position. The three cars were so far ahead that one of them was almost guaranteed to win, so the decision of who to lead the charge had to be made by team directors Carroll Shelby and Leo Beebe.

Unprecedented Le Mans controversy

Initially, Shelby and Beebe asked race officials whether they could engineer a tie so that all three of their cars came in together and were all awarded the win. The answer came back as yes, so at the next pit stop, each driver was told of the plan, and instructed to finish side-by-side on the final lap. However, the officials later changed their mind, instead stating that the car driven by Bruce McLaren (who would later go on to create plenty of incredible cars of his own) would be awarded the win. This was because he'd started 8 meters further back from the start line, so would have technically traveled the furthest.

This was despite the Le Mans rulebook having no provisions at the time for the event of a tie, leaving it technically a gray area for the race officials to make the ultimate call. After learning of the revised decision, Shelby and Beebe opted not to tell the drivers and instead let them follow the original plan, primarily to ensure that they all got across the line safely. Ken Miles, the development driver who expected to take the race win alongside McLaren and his teammate Chris Amon, ended up being unceremoniously pushed aside at the podium, only learning that he'd come in second place after his initial celebrations had begun. If he'd been allowed, Miles would have been the first driver to win at Daytona, Sebring, and Le Mans in the same year.

Two more repeat victories

After the car's initial win in '66, Henry Ford II had achieved his goal, and set his sights on other targets. However, racing manager John Wyer was keen to continue racing at Le Mans, setting up his own race team, eventually clinching the overall win again in 1968. A year later, the exact same Ford GT40 would pull off one of the most remarkable achievements in Le Mans history, taking the overall title twice in a row.

It was one of the closest-fought races in Le Mans history, with the Ford driven by Jacky Ickx and Jackie Oliver finishing only around 400 feet ahead of the second-place Porsche 908 after a mammoth 372 laps. This would mark the last time that Ford (and for that matter, any American manufacturer) ever won outright at Le Mans, although Ford did manage a class win in 2016. It was, however, only in the LMGTE-Pro class, with the car finishing 375 miles behind the overall winning Porsche.

The most valuable Ford today

The GT40's legacy as a high watermark for Ford, and for American racing in general, makes it an incredibly expensive car to buy today. Not as expensive, ironically, as the most in-demand classic Ferraris, but still comfortably into seven figures. A little over 100 examples of the car were originally built (although the exact number is debated), with dozens more recreations or cars built with spare original parts also finding their way onto the market. Buying an all-original, certified GT40 will take exceptionally deep pockets even by car collectors' standards, with the car that achieved third place at Le Mans in 1966 selling for $9,795,000 at auction in 2018.

That makes it not only the most expensive GT40 ever sold at auction, but the most expensive Ford ever, period. Even examples without Le Mans pedigree still sell for vast sums, with a roadster prototype sold for $7,650,000 in 2019 and an early road car sold for over $4,000,000 in 2016. Prices for the GT40 seem to keep rising every time a new example is offered on the market, but that means any collector lucky enough to already own one should see a healthy return on their investment if they ever decide to sell it.