The Bizarre Plane With 9 Wings Designed To Fly Across The Atlantic In 1920

On October 5, 1905, the Wright brothers successfully piloted the Flyer III around Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, for 39 minutes. They covered 24 miles during the historic flight, and would have gone longer and farther had they not run out of gas. Six years later (November 1, 1911), man dropped the first bomb from a German-built monoplane during the Italian-Turkish War in Libya.

Meanwhile, in Italy, Giovanni Battista Caproni — a great admirer of the Wright brothers — built his first plane and promptly started an aircraft manufacturing company called Società Italiana Caproni in 1908. He was such a prodigious plane builder that by the time WW I began in August 1914 had designed some 30 others and quickly became Italy's leading supplier of airplanes.

By the start of the roaring 1920s, the technology to build planes and the science behind flight was very much in the nascent stages of development, and routine commercial air travel was decades away. The primary mode of transatlantic transportation was still by ship, which typically took five days to complete.

However, Caproni had since accumulated a great deal of real-world plane-building experience, and was determined to make those lengthy sea voyages a thing of the past. He wanted to build a massive flying passenger hydroplane capable of carrying 100 passengers at a time.

Climb aboard the hydroplane bus with wooden seats

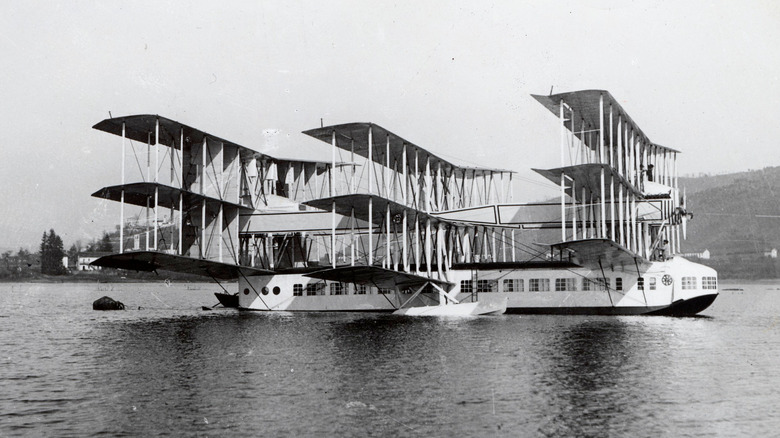

What does one of the world's preeminent plane builders of the day do? He takes all the things known to work, and not just doubles down on them ... but triples down on them. The behemoth was called the Caproni Ca.60 Transaereo, or the "Noviplano" ("nine-wing"), also known as the Capronissimo. Not confusing at all.

It had nine wings arranged in three sets of three. Caproni basically took three triplanes and tied them together with 820 feet of struts and over one and a half miles of bracing wire. Beneath it was a long bus-like fuselage that sat passengers on wooden benches. The lap of luxury, this plane was not.

The plane had a 100-foot wingspan, was 30 feet tall, and weighed over 33,000 pounds. It was so big and heavy that it had to take off from the water using stabilizing pontoons. The Transaereo needed eight crew members to fly it, with the pilot and co-pilot sitting in an open-air cockpit at the front of the plane while additional flight engineers sat in one of two control cockpits located on the front and rear wings.

Eight Liberty L-12 V12 engines, each producing 400 horsepower, were meant to get the plane into the air. It's believed to have had a top speed of 87 mph, and a cruising speed of 68 mph, and a range of 372 miles.

What goes up, must come down

The plane's short range was problematic because refueling required the aircraft to land in the middle of the ocean and resupply via ship at least a dozen stops. This added lengthy delays to a transatlantic trip that already took days, basically negating the expeditious nature of flying in the first place.

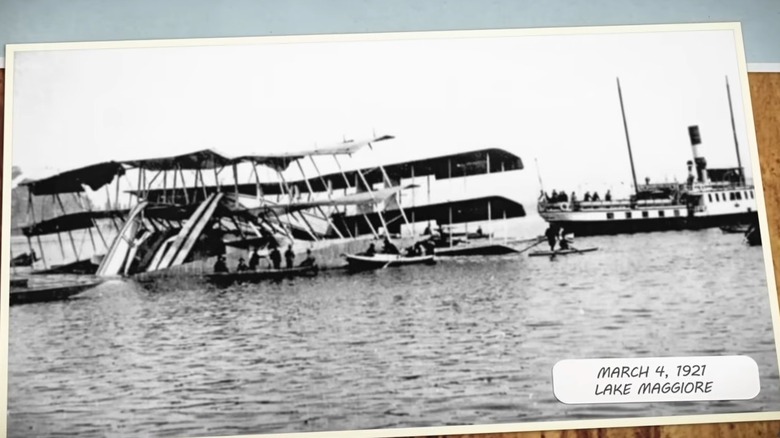

Which leads to the million-dollar question: Could it fly? According to Mustard, the first test flight happened in either March or April of 1921 at Lake Maggiore, Switzerland. After reaching a speed of almost 50 mph, it lifted out of the water — briefly. During a second test flight, it got into the air, hit 62 mph, then plunged straight into the water, destroying the plane.

However, according to Smithsonian Magazine, there was only one unexpected test flight (on March 4, 1921). Caproni wasn't even at the lake when pilot Federico Semprini, who had been testing the plane for the past month, suddenly went airborne. The reason he lifted off is still unknown, but the flight resulted in the plane's destruction.

According to Mustard, the Transaereo was doomed to fail anyway due to one serious problem: Planes don't have three sets of rowed wings because each subsequent set hampers the overall ability to create lift. Without lift, an aircraft can't fly reliably. Plus, the array of struts and wire rigging that held the beast together created incredible drag. In the end, the plane was poorly designed that — pardon the pun — flew in the face of aeronautical engineering. All of which had yet to be fully understood at the time.