Why This Planet's Newly Discovered Ring System Has Scientists Scratching Their Heads

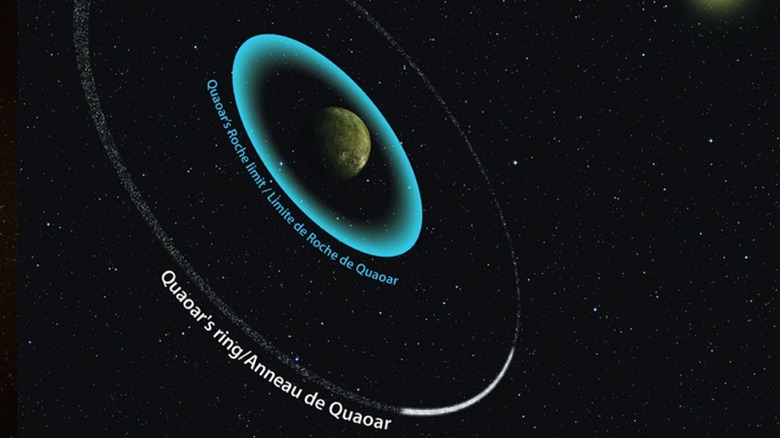

A discovery in the outer reaches of the solar system has given some of the world's top astronomers more questions than it has answers. It's related to the rings of Quaoar, a small body around half the size of Pluto and about 6 billion kilometers away from Earth. An international team of scientists made the discovery using something called HiPERCAM, a highly sensitive camera designed at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. This was then mounted to the world's largest optical telescope. The camera allowed scientists to study Quaoar's rings, which are "too small and faint" to view directly. Instead, they were spotted during a minute-long occultation — which was when Quaoar blocked the light from a distant star. Two "dips in light" were observed before and after the occultation, which scientists believe is caused by Quaoar's rings.

Like Pluto, Quaoar isn't a full-fledged planet; it is what is known as a dwarf planet, which the International Astronomical Union decided was a planet that is in orbit around the sun, maintains a round shape, and had cleared its orbit of debris. Pluto, which was the solar system's ninth proper planet until the definition was updated in 2006, only meets two of the three criteria. Quaoar was discovered in 2002 but never made it onto the list of full-sized planets within the solar system. Despite this, it does have a bit in common with a few of the solar system's planets. Like Neptune, Saturn, and Jupiter, Quaoar has rings — and, according to a recent study published in Nature, Quaoar's rings are particularly interesting.

Quaoar is changing the way we think about ring systems

It's not the rarity of ring systems in general that is surprising scientists, nor is it the fact Quaoar has a ring despite its tiny size. What has scientists scratching their heads is the fact that Quaoar's ring system exists twice as far out as they previously thought possible. It's a total of seven "planetary radii" across. The previous maximum width, which scientists refer to as the Roche limit, is around three and a half planetary radii. Before the discovery of Quaoar's rings, it was believed that tidal forces from the primary body would exceed the gravitational force holding the secondary body (the rings in this case) together. The rings would then disintegrate.

Sheffield University's Professor Vik Dhillon, who co-authored the study, discussed what the findings might mean. He says: "It was unexpected to discover this new ring system in our Solar System, and it was doubly unexpected to find the rings so far out from Quaoar, challenging our previous notions of how such rings form. Everyone learns about Saturn's magnificent rings when they're a child, so hopefully this new finding will provide further insight into how they came to be," (via Eurekalert).

We've known about planetary rings for centuries. Galileo spotted Saturn's rings with a telescope way back in 1610. But while we're aware of their existence, we're still a long way off from understanding them. Astronomers are discovering new things and developing new theories all the time, including one that could explain why Jupiter's rings aren't anywhere near as noticeable as its neighbors.