13 Fascinating Facts About The Thrust SSC, The World's Fastest Land Vehicle

The desire to break the land speed record goes back to the earliest days of the motor car, where inventors would compete against each other to see whose machine was the fastest. The race hit its peak in the '60s, when Americans Craig Breedlove and Art Arfons wound up in a closely-fought battle for speed supremacy. By 1970, the crown had been claimed by Gary Gabelich, who achieved a speed of 622 mph on the Bonneville Salt Flats in The Blue Flame. That record stood until 1983 when a British car driven by Richard Noble achieved a 633 mph two-way average in Thrust 2.

However, that simply wasn't enough for Noble, and he continued to dream of setting an even higher speed. He embarked on a mission against the odds to do just that, and his efforts were documented in a now-archived BBC documentary, "Supersonic Dreams." The documentary reveals the extraordinary lengths the team went to make the record happen, and includes plenty of surprising facts about the car and its journey to becoming a record breaker.

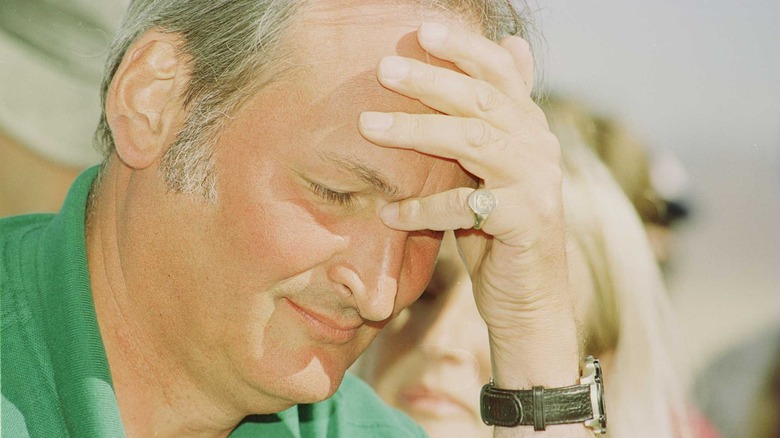

It was masterminded by one man

The Thrust SSC project would simply never have even existed were it not for the dogged perseverance of Richard Noble and his team. Noble already held the previous land speed record behind the wheel of Thrust 2, but he decided that simply being the fastest man on Earth wasn't enough. He was going to build a vehicle that would break the sound barrier, something that had never been done before, and many thought to be impossible.

To achieve such a radical feat, Noble had to spend years gathering sponsorships and putting every penny he had into funding the project. He first began work on the idea in 1990, and it took until 1997 for his team to achieve the record. Noble's personal fortune was entirely consumed by the project, and he even resorted to taking a loan out against his house to raise the necessary funds.

Piloted by Andy Green

While Richard Noble masterminded and funded the project, it wouldn't have been possible without a suitably talented (and evidently, fearless) driver. Around 30 candidates were shortlisted for the driver position but it was Andy Green who was chosen, thanks to his background as a fighter pilot in Britain's Royal Air Force. Green's girlfriend Jayne Millington was also on the crew as the head of communications, and was the only person able to communicate with Green during the high-speed runs (via The Times).

In the documentary, Jayce Millington is asked whether Green is "the right man for the job," and says, "I always thought he was going to be right as soon as we saw Richard's [...] advertisement for the driver," calling him "very cool, very competent, [and] very capable." In addition to simply driving the car, Green also took the lead in making the decision over whether any given run was safe. After all, he had the most to lose if it wasn't.

The car's designer specialized in supersonic missiles

Thrust SSC's groundbreaking design was not the product of a maverick automotive industry engineer, but rather a missile designer. After several years of searching, Richard Noble ran into Ron Ayers, a retiree who had spent his life in the defense industry helping to design supersonic missiles. Ayers wasn't initially sold on the idea, claiming in the documentary that he told Noble it was "totally impractical, don't even try it." He says he only carried on working on the project out of curiosity, so that "if some time, some idiot should try to travel supersonically, [then they'll know] what the car should look like."

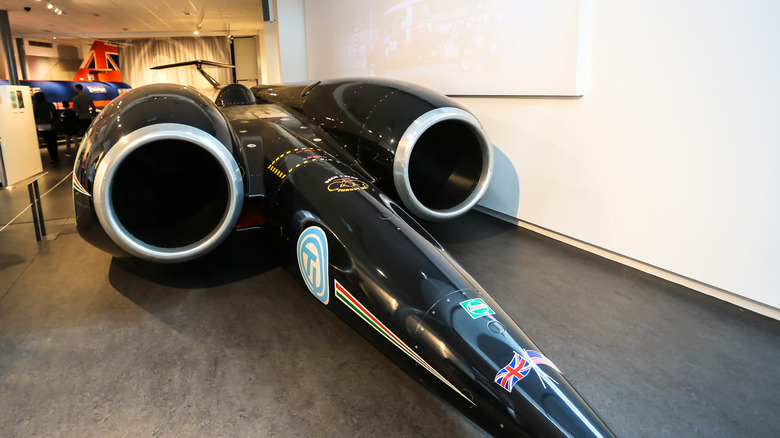

His design was unlike any other land speed record vehicle created before it, with a dual-jet engine setup, a long, narrow body, and wheels that sat much closer together at the rear than they did at the front. The team made sure to extensively test the design through computer simulation and small-scale modeling before building it in full, as the biggest danger was that it would take off into the air at full speed, which would be disastrous for the project and potentially fatal for its pilot. When the initial computer and modeling tests showed very promising results, Ayers' "totally impractical" design was given the green light to become reality.

It featured two Rolls-Royce engines

While to many people, the Rolls-Royce brand is best known for making world-beating luxury cars, a related company with the same name is also one of the world's leading aircraft engine manufacturers. The Thrust SSC used two Rolls-Royce Spey jet engines, but the only reason the team could afford them in the first place was thanks to Noble's shrewd negotiation skills. He bought the two engines used from the British Royal Air Force, claiming in the documentary that the government paid around £1.5 million (around $3.2 million today, taking inflation into account) for each one when they were new.

It's very tricky to estimate exactly how much horsepower the car was capable of producing, but most estimates put the output somewhere north of 100,000 horsepower. Unsurprisingly, the car drank a huge amount of fuel, averaging around 0.4 mpg over the run, according to the Land Speed Record website.

It used rear-wheel steering

The Thrust SSC weighed about 10 tons, which presented the design team with a unique problem. With that much weight and the added downforce produced by the car at such high speeds, it would be almost impossible to design a system capable of turning the front wheels. As a result, the team made the decision to use the rear wheels to steer the car instead. They consulted with various leading British professors and received an almost unanimously negative reaction, but decided to press ahead anyway. To demonstrate that a rear-steering car wasn't a terrible idea, the engineers made a scale model of the setup out of an old Mini Cooper.

To fit in the car's narrow tail, the rear wheels were positioned as close together as possible, with one slightly behind the other. The unconventional setup caused the team some stability issues at first, but they were eventually ironed out with the help of a more forgiving suspension. The exceptional speed of the car meant that driver Andy Green reported having to turn the wheel up to 40 degrees at high speed just to keep the car in a straight line, but nonetheless, it remained stable throughout the final runs.

The project nearly went bankrupt several times

Despite the Thrust SSC making its way into the history books and remaining undefeated to date, there were plenty of people at the time who doubted such a high speed could ever be achieved. As such, Richard Noble struggled to find backers for his project, and at times was pushed into near-critical levels of debt just to keep the project alive. After initial testing in Jordan concluded without the team hitting their target speed of 600 mph, Noble was forced to get creative to raise funds. He hosted an auction to sell off broken and used parts from the Thrust SSC's first run, with buyers hoping that the parts would become collectible once the record was eventually broken.

Even with his unique approach to fundraising, Noble's tight finances nearly shut the project down several times. At one point, the project leader claimed he was "half a million [pounds] in the red," which converts to just over $1 million at today's rates. He said that although he had put his house up as collateral, it wasn't worth anywhere near that much, and he simply had no idea what he was going to do if things didn't work out.

Thrust SSC had an American rival

Adding to Richard Noble's troubles was the fact that someone else was trying to beat the Thrust SSC team to the Mach 1 record. Craig Breedlove, an American entrepreneur, had formed a rival project called the Spirit of America, and initially seemed to have the upper hand. He had already become the first person to reach 500 mph and 600 mph and had decades of experience breaking various other speed records. The two teams eventually both met in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada in 1997, when they were both preparing for their high-speed runs at the same time.

The Spirit of America's design was significantly different from the Thrust SSC, with traditional front-wheel steering and a single jet engine rather than dual units like the British car. In the documentary, Green can be seen checking out Breedlove's car, and the size difference between the two men quickly becomes apparent. Green is significantly taller, and since the Spirit of America's cockpit is so small, he jokes that he wouldn't be able to get in and steal the car even if he wanted to. Unfortunately, during one high-speed run, the Spirit of America hit a rock, which got sucked into the engine and caused significant damage. The team had to go home and repair the car, and by the time they'd done it, Thrust SSC had already beaten them to the record.

Early testing took place in Jordan

While the car famously hit its top speed in the desert in Nevada, the initial runs took place on an entirely different continent. While presenting an early prototype of the car at a motor show, Richard Noble got into a conversation with a visitor and mentioned that he couldn't find anywhere suitable to test the car. The visitor suggested using the Jordanian desert as a testing ground, as he'd been stationed there while serving in the Army a few decades prior and remembered it being perfectly flat. By chance, Noble already knew the Jordanian King through a previous venture and decided to fly out and check out the area himself.

The man who suggested the idea, Ken Waughman, told documentary makers he was very nervous after recommending Jordan to Noble, especially since his wife later told him "they've probably built a block of flats on it [by now]." It turned out that the area was still perfectly flat and totally undeveloped, and Waughman later flew out to help the team with the initial test runs.

The tracks always required fodding

One of the key challenges facing the team throughout all of their runs was making sure that the tracks through the desert were kept free of rocks, debris, and anything else that could undermine the stability of the Thrust SSC. Every track could only be run once, since the car left such deep ruts in the sand that it was unsafe to run it in the other direction. So, for every new run, an entire new track had to be carved out of the desert.

The process of removing the debris was called "fodding," and it had to be done entirely by hand. This meant that several members of the team had to hike down each track, which was up to 13 miles long, in the scorching desert heat, collecting rocks in a bag as they went. Despite each mile of the track taking up to an hour for the team to clear, they remained upbeat throughout the ordeal. One team member told the documentary crew that "it's quite therapeutic really, once you get into a rhythm."

The car's computers kept malfunctioning

One of the biggest recurring issues the team had to deal with throughout the runs was computer failure, with several runs having to be aborted when the onboard systems failed at high speeds. During the initial runs in Jordan, it was discovered that high temperatures inside the computer's housing were causing the failures, but even after that was rectified, the problem still persisted. The mystery issues plagued the team throughout their Jordanian practice runs and were still present when the team made it to the desert in Nevada.

In one particularly hair-raising run, the car malfunctioned and shut down completely, leaving Andy Green barely able to control the car at 540 mph. He managed to get the car to a stop safely, but on a second test run, it happened again, with the car shutting off at around the same speed. It was eventually discovered that one of the chips was being shaken out of its socket during the run, and with new fastenings fitted to hold it firmly in place, the team could finally proceed with their full-speed record attempt.

Thrust SSC broke its own speed record

Thrust SSC technically became the fastest land vehicle not once but twice, as its initial record-breaking run didn't quite break the sound barrier. The first run clocked an average speed of 714 mph, comfortably beating the previous record of 633 mph. The team celebrated, but after just a night to unwind, Richard Noble was insistent that everyone should quickly regroup and try to focus on breaking the sound barrier. A few days later, the car did indeed break the barrier for the first time, creating a sonic boom that echoed across the desert. However, to set an official speed record, the team needed to turn the car around and set a second time in the opposite direction within one hour. After the car's parachutes failed, causing it to overshoot the track, the team missed out on the deadline by just 50 seconds, making the record invalid.

The team was understandably dejected, and the car was taking more and more damage after every run. Nonetheless, they patched the Thrust SSC up and attempted the record again. This time, they were successful, as the parachutes deployed as planned and the team was able to reset the car for its second run with several minutes to spare. A new official speed record was set at 763 mph, and after seven years of toil, Noble had finally achieved his goal.

The car now lives at Coventry Transport Museum

Post-record, the Thrust SSC can be seen at the Transport Museum in Coventry, England, alongside its predecessor Thrust 2 and its potential successor, Bloodhound LSR. Since it set the land speed record on October 15th, 1997, the car has not moved under its own power and instead has sat in pride of place in the Museum's Land Speed Gallery. While Breedlove continued to work on redesigning the Spirit of America with the goal of taking back the land speed record and breaking the 800 mph barrier, the Thrust SSC was retired as soon as it made its record-breaking Mach 1 run.

Breedlove sold the car to fellow record-breaker Steve Fossett and planned a new record attempt, but Fossett's untimely death in a plane crash in 2007 put those plans on ice. The original team behind the Thrust SSC disbanded after the project ended, but has staged occasional reunions since, including at the Transport Museum to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the car's record in 2022.

Thrust SSC's successor is still in the works

Although the Thrust SSC's days of record-breaking may be well and truly in the past, the minds behind it have been working on its successor for over a decade. Initially, Richard Noble led the efforts once again, but after running out of funds, the team was bought out and Noble was kicked off the project. Originally called the Bloodhound SSC, the new car was rebranded as the Bloodhound LSR, and development work resumed. However, according to its website, complications due to the onset of the Covid pandemic have prevented the team from completing any full-speed test runs so far.

Even so, the team is adamant that the Bloodhound LSR is still very much in development, with the goal of commencing the first tests in South Africa later in 2023. Andy Green is once again set to drive the car, and the team now intends to focus on breaking the record with an "environmentally friendly" rocket system, although so far, they've remained coy on the specifics.