12 Inventors Killed By Their Own Inventions

Inventors are often characterized in popular media as eccentric. They're stylized with wild hair and a disregard for their own safety or the safety of others. This is the model for your Doc Browns and your Rich Sanchezs. They do incredible things, push the collective knowledge and ability of humanity into the future, and they usually put themselves or other people in danger in the process. In reality, most inventors are ordinary people or collections of people with extraordinary ideas.

When we stop to think, it's clear that every innovation we enjoy in modern life can be traced back to an enterprising inventor, or a collection of them. The indoor toilet, refrigerators with built-in ice dispensers, the car you drive to work, and the television you watch when you get home were all crafted first inside the minds of inventors. The line between genius and ill-advised scientific misadventures is awfully thin and some inventors lean a little closer to the stereotype.

These ill-fated individuals took incredible risks in the pursuit of knowledge, or else they were just terribly unlucky. Whatever the reason, sometimes when you're trying to bring something new to life, you end up accidentally ending your own.

Abu Nasr al-Jawhari

Abu Nasr Isma'il ibn Hammad al-Jawhari was a lexicographer by trade. He is most well known for having written "The Crown of Language and the Correct Arabic," a volume containing 40,000 dictionary entries (via AbeBooks). The second thing he's known for is the way he died.

In addition to lexicography, al-Jawhari was something of an inventor. Toward the end of his life, he constructed a set of artificial wings made of wood and rope. The specifics surrounding his precise motivations are unclear, having occurred more than a thousand years ago. Some believe it was an earnest attempt to achieve powered flight a millennia before the Wright Brothers. Others believe that al-Jawhari was taken by a sudden delusion that he was a bird (via History of Psychiatry).

Whatever his motives, the results are known. He climbed to the roof of a mosque with his wings neatly affixed to his body, and he jumped. He probably got a few attempted flaps in before he struck the ground and was killed by the impact.

William Bullock

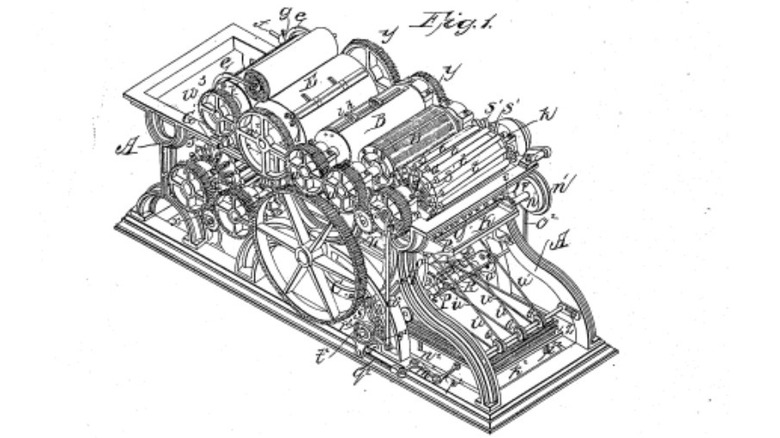

One might think that the making of books and newspapers is a fairly unadventurous endeavor. Jumping from a tall building is one thing but the most dangerous thing about printing newspapers is usually the ink stains on your clothes. That is, unless you're the 1863 inventor of a new kind of printing press, William Buckley.

By the middle of the 19th century, the printing press had been around for 400 years, and countless people had taken a stab at improving its design. Before Buckley, many newspapers were using the Rotary Drum Press developed by Richard M. Hoe. Buckley improved upon the current designs and incorporated ideas from other inventors to develop the Web Press. It used a continuous roll of paper, printed on both sides of the sheet at the same time, and even cut the paper when it was done (via History of Information).

Bullock's press allowed newspapers to be printed more efficiently and, as a result, various newspapers invested in the new machine. That's where Bullock got in trouble. According to History of Information, one of Bullock's presses was purchased by the Philadelphia Public Ledger. It was there that in 1867 Bullock was making adjustments to the recently installed press when a belt got stuck. Bullock tried to kick the belt into place and his leg got jammed in the machine. He later developed gangrene from the injury and died during an operation to amputate the leg.

John Day

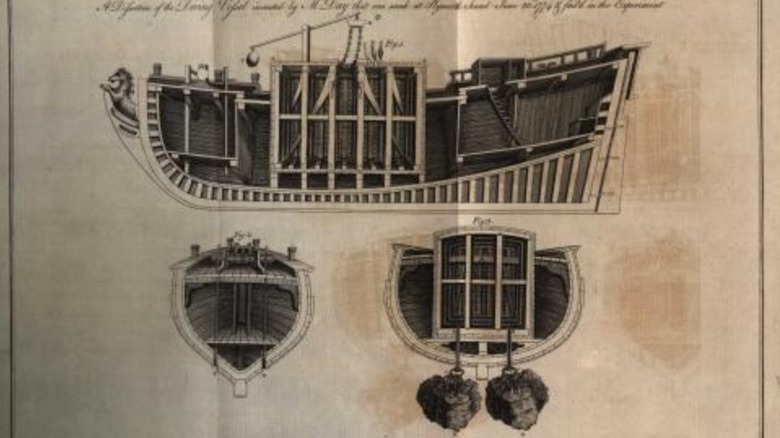

Considered by some to be the first death of a submariner, John Day died in 1774 while testing an experimental diving chamber. The account of Day's attempt at building a submersible chamber and subsequent death was published in the 1775 dissertation by Nikolai Detlef Falck.

The story begins with a previous attempt which reportedly went well. During that early outing, John Day constructed a chamber within a boat that he allowed to be covered by the rising tide. Once underwater, Day stayed submerged for approximately six hours before resurfacing unharmed (via Royal Museums Greenwich). Buoyed by that success, Day wanted to take his experiments even further by going deeper.

He purchased an old sailing vessel named The Maria and built an air chamber inside. The chamber was 12 feet by 9 feet by 8 feet and was reinforced against the pressure of the water. At least, that was the plan. He attached twenty tons of rocks to the ship, allowed the rest of the ship to take on water, and sunk his creation 120 feet beneath the surface of the Plymouth Sound. It's unclear precisely why this experiment failed while his previous one succeeded. Maybe the water pressure was too great or maybe he had insufficient air inside the chamber. Whatever the reason, John Day never resurfaced.

Andrei Zhelznyakov

In 1990, the United States and the Soviet Union signed a chemical weapons accord that ostensibly ended any development of chemical weapons by the two signees. Prior to that, however, the production of chemical weapons was in full swing. Three years before the accord was signed, Andrei Zhelznyakov was working as a chemical weapons scientist for the Soviets. His work involved the development of a new nerve agent that became known as novichok. Although, according to The Guardian, the Russian government maintains they never had such a program.

In any event, Zhelznyakov himself reported working on the nerve agent and being exposed after a hood malfunction in the lab. He reported seeing red and orange circles in his eyes and ringing in his ears. It appears he knew he was in trouble as he recounted sitting down in a chair and telling the other people in the lab, "It's got me."

Zhelznyakov didn't die right away. He lived for several years after his exposure, during which he attempted to expose the Soviet chemical weapons program. Five years later his nervous system was destroyed, and his organs were failing. A year after that he was dead from damage caused by the nerve agent he created.

Alexander Bogdanov

The early 20th century was a good time to be a renaissance man. Several scientific fields including biology and medicine were in the process of being revolutionized. It was the perfect environment for someone like Alexander Bogdanov. He was, by all accounts, a diverse thinker and innovator, making a name for himself as a philosopher, economist, and author of science fiction (via National Library of Medicine). He also believed a person could be rejuvenated and perhaps attain eternal life through blood transfusions.

Bogdanov performed more than ten transfusions on himself, apparently with positive results. According to Bogdanov, he attained greater eyesight and stopped balding, among other physical benefits. What's more, his contemporaries reported that he looked a decade younger after taking up the practice (via New World Encyclopedia).

In 1925, he founded the Institute for Hematology and Blood Transfusions and was subsequently asked to examine Vladimir Lenin's brain and revive him if possible. As far as we know, those efforts failed. Bogdanov continued his transfusion experiments for the next several years until, in 1928, something went wrong. Bogdanov injected the blood of a student into his body. That student, it was later found, was carrying tuberculosis and malaria, and may have had the wrong blood type. Bogdanov quickly died.

Luis Jimenez

In the mid-1990s, the city of Denver commissioned a statue from artist Luis Jimenez. The Denver International Airport was in the process of being completed and the city wanted a work of art to stand outside, where travelers would see it on approach (via Uncover Colorado). Jimenez envisioned a massive horse, reared up on its hind legs, and he got to work.

If you travel to or through Denver, you'll see the 9,000-pound statue standing 32 feet tall outside of the airport's entrance today, where it has been since 2008. Its wild blue coloration and eyes beaming with red light are hard to miss and harder to forget but it's the story of what happened to the artist which truly colors the experience of seeing it.

After years of work, as the statue was nearing completion, a piece of the statue fell and struck Jimenez. The statue severed an artery in the artist's leg that ultimately claimed his life (via CPR News). Jimenez was 65 years old. That might have been the end for Blue Mustang, if not for the efforts of Jimenez's family and friends. Those close to the artist finished his final work after his death.

Valerian Abakovsky

By the early 20th century, travel by rail had become one of the best ways to move people or cargo long distances. Trains had been in use for about a century by this time and had proven themselves effective modes of transportation, but some engineers and inventors felt they could be improved upon. In 1919, German engineer Otto Steinitz crafted the first amalgamation of a train and an airplane when he attached an aircraft engine and propeller to move a train car at speeds of up to 150 kilometers per hour (93 mph) (via Russia Beyond). Having heard about the Germans' success, Valerian Abakovsky convinced Soviet officials to let him make his own plane-powered train car.

The car, dubbed the Aerowagon, was intended to transport government officials and important cargo quickly over long distances. In addition to the airplane parts, Abakovsky made other modifications to the train car in the hope that it would travel even faster. The nose was shaped to a point and the roof slanted, making the car more aerodynamic.

By the time it was finished, the Aerocar could travel at speeds up to 140 kilometers per hour, (86.9992 mph) nearly on par with the German results. Test journeys were successful and the Aerowagon was loaded up with 22 people including Abakovsky. The initial journey went fine, but on their return, the train derailed going at least 80 kilometers per hour (49.7 mph). Six of the 22 passengers were killed in the accident, including Abakovsky.

William Nelson

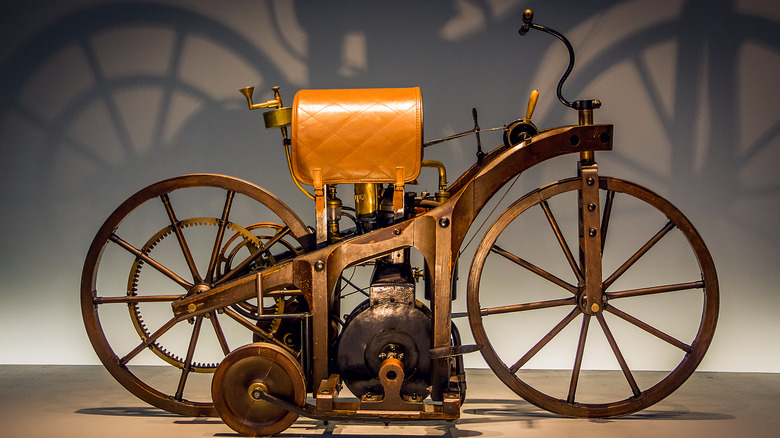

General Electric has a long history of invention that ties all the way back to Thomas Edison and the invention of the incandescent lamp. In the years since the company's formation, it has introduced to the world the central power station, electric trains, the x-ray machine, kitchen appliances, vacuum tubes, and so much more (via GE). Along the way, however, some of their innovations had deadly results.

William Nelson was an inventor for GE at the turn of the 20th century. The company had previously had some success at electrifying trains — and would later go on to craft an early electric car in 1914 — but in the fall of 1903, it was working on a smaller form of transportation. Nelson wanted to motorize a bicycle by adding an attachment, not dissimilar to modern motorized bicycle mod kits.

By all accounts, the motorized bicycle worked. In fact, it may have worked too well. As explained by The New York Times, Nelson took his invention for a test run on the afternoon of October 4, 1903. During the course of his drive, he ended up on a hill, fell from the bicycle, and died of his injuries. He was only 24 years old at the time.

Henry Smolinski

When we envision the future, there are almost always flying cars. That's probably why we keep trying to make them work, even after so many failed attempts. This is the story of one of those attempts.

Henry Smolinski worked at Rocketdyne, a rocket engine production company, for more than a decade. Flying was in his blood. When he left Rocketdyne he formed the company Advanced Vehicle Engineers with his friend Hal Blake. They had one purpose: the design and production of a flying car. Rather than build a flying car from scratch, the pair hit upon an idea that was either brilliant or completely unhinged. They were going to take an existing car and an existing airplane, chop them up, and mash them back together (via Mental Floss).

Their first model, the AVE Mizar, started with a Ford Pinto and a Cessna Skymaster. The idea was for the vehicle to spend most of its time being an ordinary car. When you wanted to fly, you'd drive to the airport, attach the Cessna parts to the car, and fly away. At your destination, you'd detach the plane parts and drive away. Despite the unconventional design, it seemed to work. Over the course of three months, the vehicle underwent a number of test flights. However, during its last test flight, Smolinski took Mizar up himself along with his partner Hal Blake. A couple of minutes after takeoff, the right wing folded in, and the Mizar crashed, killing both men.

Franz Reichelt

Franz Reichelt was a tailor born in Austria in 1878. By the time he was 30, the first powered flight had been achieved and Reichelt set his mind to work, building a parachute suit. Parachutes had been around at this point for more than a century (via History) but with the advent of airplanes, their utility had increasing importance. Reichelt believed he could improve upon contemporary parachute designs by incorporating them into the flight suit itself. That's something he was able to accomplish with his skills as a tailor. The result was something akin to modern wingsuits and Reichelt thought he was really onto something.

He started by crafting suit designs and strapping them dummies, which he threw from the roof of his shop. Despite the failed dummy tests, Reichelt remained convinced that his parachute suit would work. He was so convinced that, in 1911, he tested one of his suits on himself. The tailor jumped from a window 26 feet high and subsequently broke his leg (via Atlas Obscura). Despite the painful and injurious failure, Reichelt believed his suit didn't work because it didn't have enough time to deploy the flaps. To his mind, he just needed to jump from something higher.

A year later, in 1912, Reichelt set up a public demonstration and jumped from the first deck of the Eiffel Tower, some 180 feet up. The suit didn't work and Reichelt died on impact.

Thomas Midgley, Jr.

The life story of Thomas Midgley, Jr. is enough to fill an entire book. While most people don't even know his name, there are few who have had such a heavy and lasting impact on the world. During his life, he worked for General Motors studying and innovating car engines. In the course of his efforts to improve combustion engines, Midgley developed leaded gasoline (via Britannica). It improved the engines but exposed countless millions to potential lead poisoning.

Later, he worked on the development of CFCs for use in air conditioners and refrigerators. Once again, his work was a success, but the chemical compounds ate a hole in the ozone layer. The human population and the global environment still wear the mark of Midgley's inventions to this day.

In the 1940s he contracted polio and was paralyzed from the waist down. According to Popular Science, he continued to work but disliked being lifted in and out of bed by other people. He set his inventor's mind in search of a solution and found it in a custom-built system of ropes and pulleys. The device seemed to work — until it didn't. Thomas Midgley, Jr. was found dead in his bed in November of 1955, strangled by the ropes of his own invention.

Horace Lawson Hunley

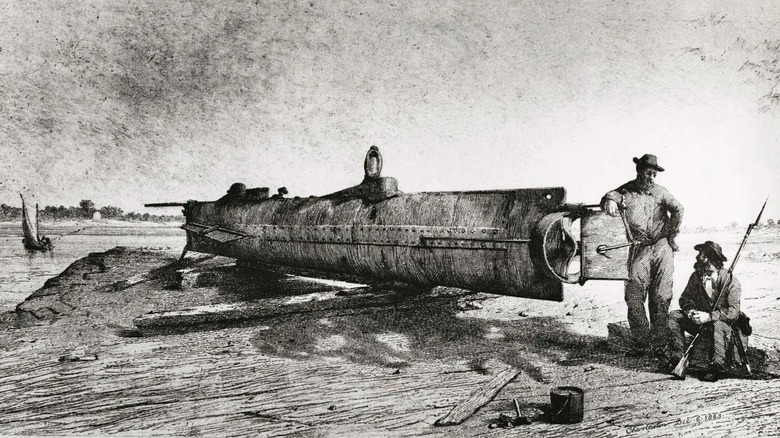

In the midst of the American Civil War, Horace Lawson Hunley built the world's first war submarine for the Confederate forces. The vessel was made of a cylinder boiler, stretched forty feet long, and held a crew of eight. When in use, one crew member steered the sub while the remainder turned a crank that drove the propeller. Hunley's submarine enjoyed a successful test run in the summer of 1863 but that would be the last good time in the submarine's existence.

The sub was later shipped to South Carolina where it underwent additional tests. During one, the craft descended into the water with the hatch still open. All but two crewmembers drowned. Following that tragedy, Hunley struggled to find a replacement crew willing to descend into the depths inside his creation. So, he stepped up himself. In October of 1863 Hunley and his crew descended into Charleston Harbor. None of them would return alive (via History).

Later, the ship was recovered and repaired, and a new crew was assembled. This time, they took the submarine into battle. They fired a torpedo at the U.S.S. Housatonic, sinking it. However, on their return journey, the submarine sank again, killing a third crew. It remained where it fell until 2000 when it was raised and put on exhibit in Charleston.