This 45,000-Year-Old Leg Bone Will Change How Old You Think We Are

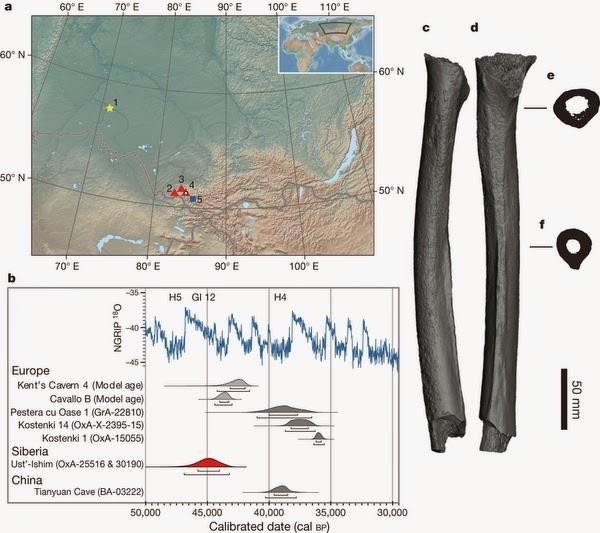

A paper has been published by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig which shows the results of their decoding of a set of genes from a 45,000-year-old modern human male from Sibera. It'd be enough to noteworthy that this man was nearly twice the age of the otherwise eldest modern human whose genome was sorted, but there's another point to be had, as well. This leg bone not only has modern human genes, but Neanderthal as well.

It's an established fact that humans share genes with Neanderthals – we've still got traces of Neanderthal genes in our bodies today.

Inside this bone, according to researchers, "the genomic segments of Neanderthal ancestry are substantially longer than those observed in present-day individuals, indicating that Neanderthal gene flow into the ancestors of this individual occurred 7,000–13,000 years before he lived."

Above: Svante Pääbo (left) and Nikolay Peristov discuss the Ust'-Ishim discovery. Image from Bence Viola/Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Many, many generations of humans co-existed with Neanderthals, it would seem. The authors of this paper suggest that "the admixture between the ancestors of the Ust'-Ishim individual and Neanderthals occurred approximately 50,000 to 60,000 years BP, which is close to the time of the major expansion of modern humans out of Africa and the Middle East."

One very interesting point on mutation also pops up. Based on their observations of change over time in fossils on record, these scientists estimate a mutation rate of 0.43 × 10−9 per site per year.

That might not mean a whole lot to the lay person, but the key to this equation very well might: "these rates are slower than those estimated using calibrations based on the fossil record and thus suggest older dates for the splits of modern human and archaic populations."

In other words, the modern human is much older than science previously suspected.

Another point from the paper suggests that there was more than one expansion – waves of expansions and exits, that is – from the cradle of humanity, Africa.

"The finding that the Ust'-Ishim individual is equally closely related to present-day Asians and to 8,000- to 24,000-year-old individuals from western Eurasia, but not to present-day Europeans," says the paper, "is compatible with the hypothesis that present-day Europeans derive some of their ancestry from a population that did not participate in the initial dispersals of modern humans into Europe and Asia."

You can find the entire paper in Nature. The issue in question was published on October 22nd, 2014.