Smart Home, Smartphone, Smart Selling: Xiaomi's Power Plan

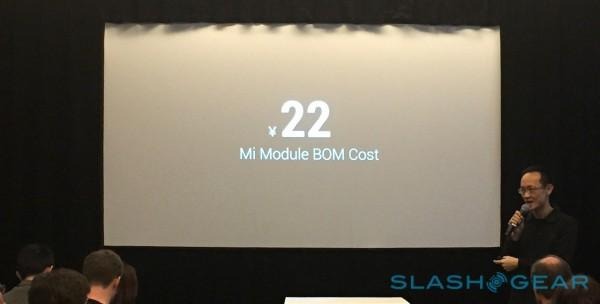

Xiaomi's schemes for smart home domination rest on a three dollar gizmo and a willingness to practically give it away, a warning note for rivals that, should a US launch happen, the Chinese curiosity could upset the game considerably. The Xiaomi Mi Module is a 22 yuan add-on linking regular appliances – whether they be heaters, rice cookers, or, as Xiaomi has already created for smog-heavy China, an air purifier – to the cloud, but rather than trying to fence the whole thing in, the company hopes to offer them at cost. It's a strategy that's at odds with how many of Xiaomi's competitors do business, and one which symbolizes quite how well a different approach can resonate with consumers.

Mi Module is, on the face of it, not especially different from many of the other Internet of Things (IoT) adapters we've seen from the connectivity companies. It serves a relatively straightforward purpose, too: bridge the internal language devices speak with a common one for the sake of interoperability.

What's different is Xiaomi's willingness to sacrifice profits over hardware sales. Not only does it envisage the cost of the Mi Module dropping significantly over time – the goal is 10 yuan, or about $1.50 – but it intends to keep offering to any third-party vendor at cost, or what the widget costs Xiaomi to make.

If you think that sounds like a nightmare for quarterly revenues, you're not wrong. In fact, though, it's a strategy shared across Xiaomi's entire range which – although we know them best for smartphones – encompasses everything from TVs through headphones, portable batteries, home appliances, and even "bunnies".

Xiaomi sold 1.97m bunnies in various sizes in 2014, but stuffed toys still aren't enough to turn a Silicon Valley style profit.

"We never share information on our margins," Xiaomi President Lin Bin demurred at yesterday's event, going on to argue that the company's focus was always on user growth and experience over revenues.

That doesn't come as too great a surprise, given Xiaomi's recent financial performance. The company's wafer-thin profit margin came as something of a shock for many, especially given the huge numbers of products being sold during things like single-day sales.

One such sale, through popular Chinese store Tmall, for instance, saw Xiaomi sell 1.16m smartphones in a single day, while its other products dominated the most-popular lists in every other category they were in.

The goal is experience. Not just at the point of sale – the feeling of getting a good deal, though that's undoubtedly part of Xiaomi's plan for winning more "fans", as users refer to themselves – but in how having scale can then shape how different platforms and products co-exist.

Mi Module's control functionality, by way of example, is not only funneled into a single app for multiple devices, but baked into the core of MIUI, Xiaomi's Android OS. Accessing smart home controls is a side-swipe away from the lockscreen, then, rather than another free-floating app buried somewhere in the launcher tray.

Meanwhile, by opting for fewer products but each with longer life cycles, as for a long time Xiaomi did with its smartphone range (a single SKU per market), the company benefits from economies of scale. Component prices fall, and then so do device prices, and Xioami's user-base swells. The stats suggest that the combination of engagement and affordability works.

Is Xiaomi alone in some of these strategies? No, of course not; Apple's HomeKit, for instance, doesn't have a common communication module, but does intend to bring products from multiple vendors under the same umbrella of control.

Yet where Apple is – to the benefit of consistent user experience, but often the frustration of participating vendors – heavily focused on controlling the platform, Xiaomi's approach is more freewheeling. Fitting, perhaps, for a company which updates its core mobile platform once a week, which shares the task of prioritizing changes with an army of vocal fans, and which rewards the greatest contributions from staff and fans alike with "popcorn parties".

It's not necessarily the best way of doing things, but the risk to other manufacturers – particularly those in the West - is that it's such a different one, when taken as a whole, from the status-quo. Winning hearts and minds can be done in many different ways, and Xiaomi's formula is so unusual that it could leave big names elsewhere on the back foot as they compete with its blend of crowdsourced growth.