Facebook Clarifies Its "Data Sharing" Partnerships

The PR team at Facebook is undoubtedly working overtime these days. Just hours after a major exposé, the social networking giant issues a public clarification and defense, in contrast to previous days, even weeks, of silence it used to practice. Then again, when you're as embattled as Facebook, you do have to do damage control ASAP. So when the New York Times once again called attention to extremely favorable partnerships that may have shared too much user data with companies, Facebook has unsurprisingly come out with a statement that unequivocally denies any wrongdoing, legal or moral.

It's not just Facebook, to be fair. Tech companies whose names have been dragged into this controversy have immediately reached out to news outlets to distance themselves from the impending scandal. In a nutshell, all of them are claiming that their features only used as much user information or friends list as needed to, for example, send messages or make recommendations. They all insist they have not read private messages nor asked Facebook for permission to do so.

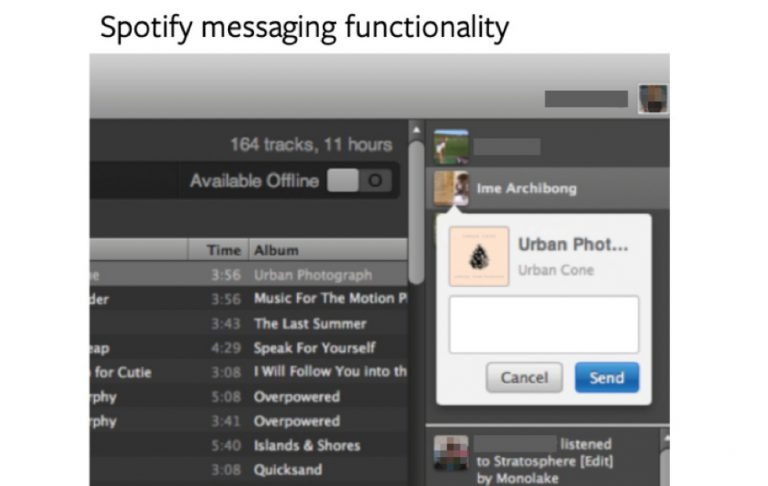

Facebook's statement echoes this and explains that it was an experimental feature that was shut down already three years ago, contrary to the NYT's report. The feature was supposedly limited only to being able to send, receive, and delete messages on, say, Spotify and Netflix. And in order for them to do so, they need to be able to access users' messages and friend lists. Facebook refutes the implication that it basically handed users' data over to these third-parties. Of course it didn't nor did it have to. Those third-parties already could on their own.

Unfortunately, we can only take these companies' words at face value. None of the companies deny giving and receiving access to user messages, friends lists, and other information, only that they did not go beyond what was necessary to implement the feature. But the way these permissions work, there might also be other pieces of data that become exposed to those partners and it's only their self-control and laws that prevent them from taking advantage of that access.

Facebook's statement indirectly highlights one of the problems of these modern platforms. Inter-connected services are becoming more common, even expected, and users often accept permissions requests without a second thought. They certainly don't expect that logging into a service or app using their Facebook account would give third-parties access to more data than they thought they wer giving.