The Magnavox Odyssey: The Forgotten Pioneer Of Gaming Consoles

If someone asked you to name the very first video game console, what would you say? The Nintendo Entertainment System? No, that launched in 1983, well into the game industry's life. The Atari 2600? That might've been the first true multi-cart system, but that launched in 1977. Atari's first "Pong" console? Close, but the real progenitor of home gaming actually managed to beat out the 1972 release of "Pong" by just a few months: the Magnavox Odyssey.

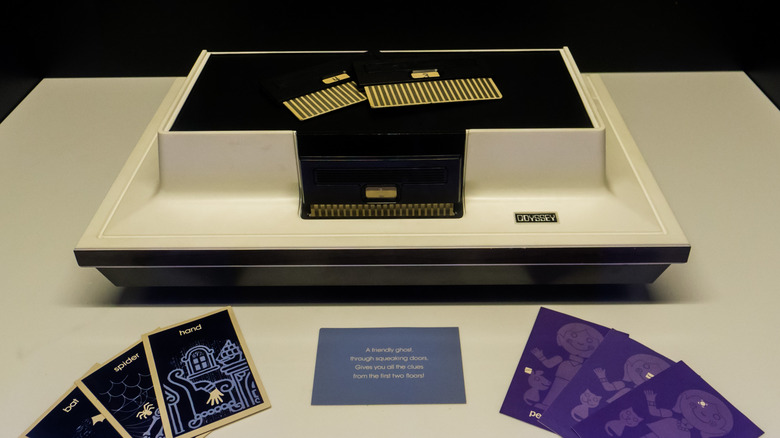

Originally released in the summer of 1972, the Magnavox Odyssey is generally recognized as the very first home gaming console, connecting to televisions and allowing kids and adults to experience an entirely new kind of entertainment experience. Compared to today's gaming hardware, the Odyssey is downright primitive, but in a time where a "game" was something you only played outside or on a kitchen table, it was the first step into a brave new world — not to mention what would one day become a billion-dollar industry.

The Odyssey was developed by Ralph Baer, a man who would go on to receive a National Medal of Technology

While the Odyssey was released in the summer of 1972, it's believed to have been in some form of development as far back as the 1960s. The Odyssey was created by German-American engineer Ralph Baer, who had been tinkering with the idea of electronic gaming for over a decade, having previously developed a prototype console colloquially known as the "Brown Box." Fun fact, Baer actually received a National Medal of Technology from President George W. Bush in 2006.

While the Odyssey was overshadowed by the earthshaking success of the release of "Pong" that same year, it's a fact that without the Odyssey, "Pong" wouldn't even have come to be. Nolan Bushnell, the Atari founder who brought "Pong" to the world, was directly inspired by the Odyssey's tennis gameplay after trying it out at a Magnavox product showcase. This lead his burgeoning company to refine the concept further into the classic rallying game we know and love.

The Odyssey featured two hard-connected controllers with one button and two knobs

The Odyssey console was a little monolith of black and white plastic with a small, stylish strip of wood paneling. Connected to the main unit via a pair of thick, beige cords were the two controllers, small, thick boxes with a pair of knobs on each side. These knobs would be used to control the vertical and horizontal movement of the objects on screen, though the left knob also had a smaller, supplementary knob sticking out of it that could offer situational control depending on the game. Each controller also featured a single reset button on top for resetting player positions or, in the case of sporting games, relaunching the ball.

As opposed to modern consoles, which are computers in themselves merely using your TV as a conduit, the Odyssey didn't actually have any onboard computing. Rather, it would interface directly with your TV's circuitry, using its tubes to project the simple images of white lines, boxes, and dots. The Odyssey didn't even have a dedicated power button; the console would power up automatically when you snap one of its game cartridges into the front slot. Each cartridge would subtly alter the movement of the projected shapes.

[Image by The History of How We Play via Wikimedia Commons, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC0]

The Odyssey was powered more by your imagination than your television

As a prototypical game console, the Odyssey was only capable of projecting a handful of simple shapes onto your TV screen. Things like colors or images simply weren't possible. So, rather than trying to crack that nut, Magnavox instead packed the Odyssey's box with a stack of colorful screen overlays. These transparent acetate sheets would be placed over your TV screen to create the illusion of game screens like a tennis court, a haunted house, a ski track, and more. You would need to consult the user manual to know which combination of overlays and the Odyssey's twelve cartridges needed to be used to actually get a functional game going.

Since the Odyssey couldn't handle graphics, it obviously couldn't do things like logic or scorekeeping. Again, this was left to physical peripherals. In addition to the overlays, the box contained items like scoreboards, playing cards, dice, fake money, and other things you may expect to find bundled with a board game. Players needed to keep their own scores and measure points effectively on the honor system to keep a game fair and consistent. You needed a bit of imagination and patience to make the whole thing work.

The Odyssey only sold around 350,000 units, not exactly a commercial superstar, but it made a massive mark on entertainment history, setting the stage for the smarter, stronger gaming hardware that would follow in its footsteps.