The Steamships Of The Great White Fleet: America's Lap Around The World

The largest operator of aircraft carriers by a wide margin, the United States knows that controlling the sea goes hand in hand with global stability and economic progress. However, the United States was not always the ocean power it is today.

Between the U.S. Civil War and the United States' emergence as a superpower after World War I, a crucial but often overlooked period of imperialism played a significant role in the growth of the U.S. Navy and the nation itself. By the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the United States had acquired an empire that spanned from the Caribbean Sea to the Philippines. Governing this empire would demand the highest level of technical innovation and an ocean-spanning navy.

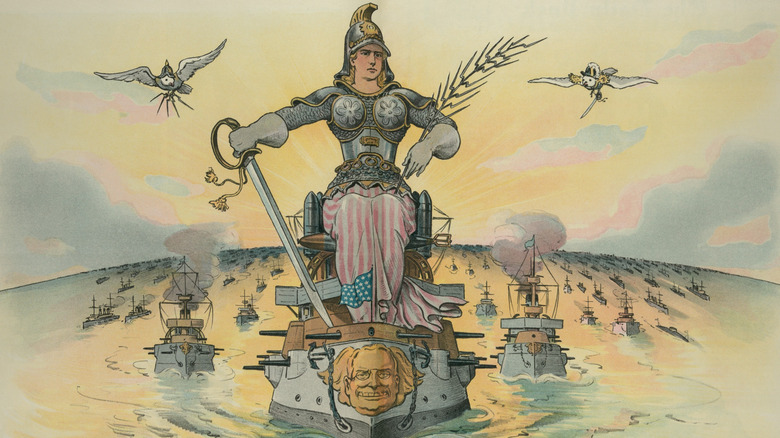

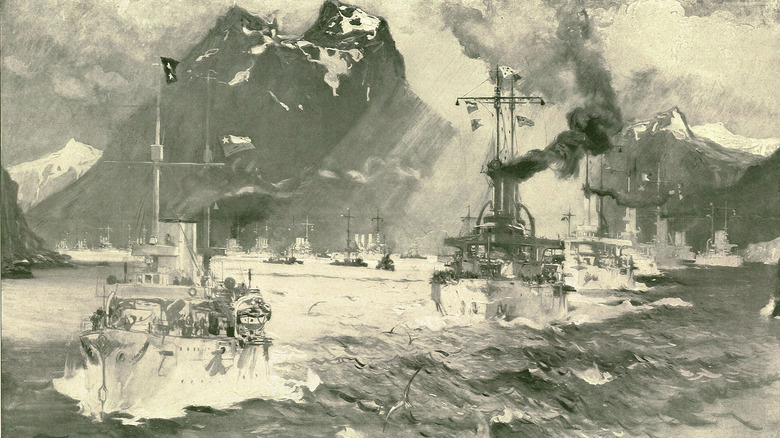

There to help with this undertaking was the Great White Fleet, a group of pre-dreadnought battleships painted brilliant white that would circumnavigate the globe, stopping in dozens of ports. The purpose? An opportunity to refine naval procedures and train sailors on extended life at sea, certainly. However, the Great White Fleet was also a gentle reminder that the United States had arrived as an imperial power with a top-tier navy that just might end up in a port near you — whether you wanted it there or not. Let's take a look at what inspired the creation of the Great White Fleet and its impact.

Naval technology innovations set the stage for the fleet

Inventor Thomas Newcomen developed the world's first steam engine in 1712. (James Watt also had a lot of influence on the invention of the steam engine, but that story is for another time.) By the turn of the century, engineers and inventors would adapt the engine to maritime use. Initially wooden craft driven by side-mounted paddlewheels, the steamship would evolve over the coming decades with a succession of inventions.

The SS Savannah became the first steamship to make an Atlantic crossing (albeit primarily under sail power) in 1819. The paddlewheel began to disappear in 1836 when inventors John Ericsson and Francis Smith invented the screw propeller. Seven years later, the first iron-hulled, screw-driven ship of scale, the SS Great Britain, left the docks. Over time, wooden hulls disappeared, along with masts and sails. The USS Monitor and CSS Virginia slugged it out in a duel in the Virginia harbor in 1862, withdrawing in a tie when cannonballs failed to penetrate the ships' iron skin.

A quarter century later, naval officer and lecturer Alfred T. Mahan published a pivotal treatise: "The Influence of Sea Power Upon History." In it, Mahan analyzed the role of the sea in the rise of the British Empire, positing that sea power was the key to global power. The theory electrified politicians and planners alike, including an ambitious young man who would serve as Assistant Secretary of the Navy before becoming President of the United States.

Why did this peacetime fleet tour set sail?

Teddy Roosevelt, a famous outdoorsman and adventurer, became president in 1901. He was a staunch expansionist and proud promoter of his beloved nation, which had grown significantly. Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and other far-flung territories had been under American control since 1898. Governing and securing these territories required mastery of the sea, and naval technology happened to be in a fascinating period when sail power had fallen by the wayside. However, the dreadnought battleship had not yet risen, and a cautionary tale from the other side of the world demonstrated a danger to any would-be naval power.

In 1905, the Russian Baltic fleet went to war with Japan. The hapless Russians had sailed around the world on a harrowing journey, arriving in Japanese waters battered and ill-prepared for battle, only to suffer an annihilating defeat. Roosevelt wanted to ensure that his modern navy, equipped with the latest navigation, communication, propulsion, and weapon technology, would fare better in a similar situation, particularly with potential competitors for Pacific power.

The Great White Fleet, as it came to be known, was Roosevelt's brainchild. To demonstrate the capability of America's new navy, a peacetime fleet would circumnavigate the globe. The voyage would include dozens of stops at ports worldwide, showcasing America's maritime prowess. It was the physical manifestation of Roosevelt's foreign policy and message: Interfering with American ambitions on the geopolitical stage may result in a battleship squadron steaming your way.

The Great White Fleet had an impressive lineup

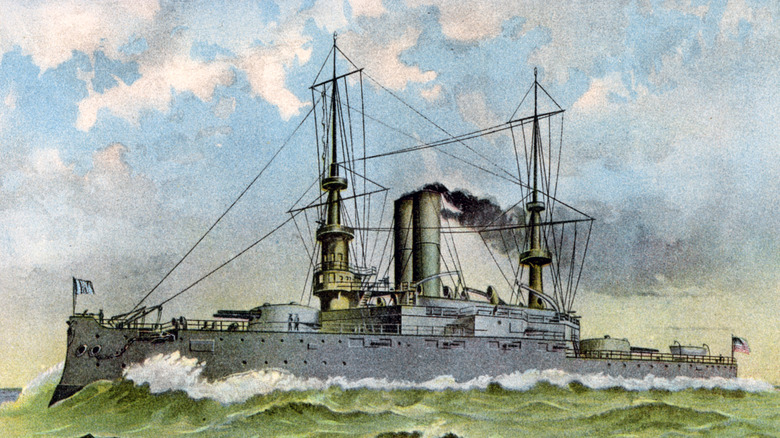

The Great White Fleet was a force to be reckoned with and consisted of two squadrons, each with eight of the finest battleships the navy could muster, split into two divisions of four ships each. The roster included the USS Connecticut, Kansas, Louisiana, Vermont, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Georgia, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Virginia, Alabama, Illinois, Kearsarge, and Kentucky. Six torpedo boats and auxiliary ships accompanied the fleet in support roles.

Launched in April 1907, the pre-dreadnought battleship USS Connecticut was at the time one of the finest ships on the planet and the flagship of the Atlantic Fleet. She was gargantuan for the day, with an overall length of 456 feet, a beam of 77 feet, and a displacement of nearly 18,000 tons. Her crew consisted of 55 officers and 1,103 enlisted men. Though Connecticut was the latest and greatest, she was just a fraction of the power represented by the Great White Fleet. The 15 other pre-dreadnought battleships also each brought more tonnage, crew, and armament to the endeavor.

To connect all of the ships together visually, the hulls all received a dazzling coat of white paint. Then, after months of preparation, the Great White Fleet departed, passing review before President Roosevelt as he watched from the presidential yacht Mayflower on December 16, 1907.

The fleet faced some technical and logistical challenges

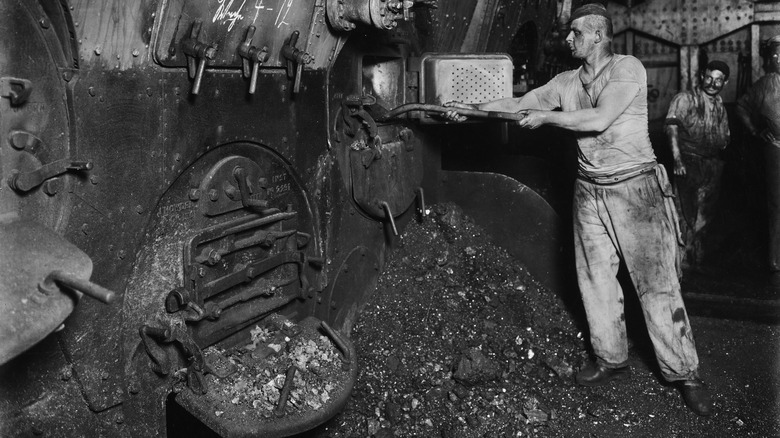

Supplying a steam-powered fleet around the world is a major technical and logistical challenge. Aside from food and fresh water to keep the crew alive and healthy, you also have to procure enough coal to feed the engines. Though the Great White Fleet's voyage was likely quite glamorous for the topside officers and crew, the sailors tasked with feeding the boilers had a markedly different experience. They would have been scampering up the ratlines to the masts and yardarms a generation earlier, trimming sails. Now, they were mired in a hot and dark boiler room, shoveling seemingly endless amounts of coal to create the steam that would drive the engines.

The USS Connecticut alone employed two vertical triple-expansion steam engines powered by a dozen Babcock and Wilcox boilers capable of producing as much as 16,500 horsepower. The engines did not always run at full capacity, but they pushed the Connecticut to as much as 18 knots at full steam. The United States government contracted several suppliers to ferry coal to the fleet while it was underway. During fueling stops, every man would load coal into the holds to replace what they had burned.

The Great White Fleet had an epic voyage

The Great White Fleet's first stop was south of America's new sphere of influence in the Caribbean in Port of Spain, Trinidad. There, it loaded up on coal on December 23, 1907. Two weeks later, it anchored in Rio de Janeiro. The Brazilian navy saluted the American fleet as it departed for the treacherous Straits of Magellan. Rounding South America, the fleet stopped in Chile and Peru before a three-month tour of the U.S West Coast occurred via stops in Coronado, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Cruz, and Monterey. Naval personnel enjoyed ceremonial banquets and warm welcomes wherever they went.

After a refit, the fleet headed west. On July 16, 1908, it stopped at the United States' new Pacific territory: Hawaii. Then, the fleet continued to pass through ports in Australia, Japan, and China before stopping in Manila, Philippines.

The third leg of the journey commenced on December 1, 1908, with a 12-day journey to Colombo, Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka). From there, the fleet entered the Arabian Sea, followed by the Red Sea, and then traversed through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean. In a show of goodwill, the ships split up to make calls in several cities there. The Connecticut, Illinois, and the auxiliary ship Culoga even aided an earthquake-relief effort in Italy, showcasing the fleet's humanitarian side. By February 6, 1909, the fleet departed Gibraltar on the final 16-day stint back to Hampton Roads, where it arrived on February 22, 1909.

The Great White Fleet influenced relations with Japan

By the time the Great White Fleet returned, it had covered 43,000 miles over 14 months. Theodore Roosevelt had only two weeks left as President, but he would leave office knowing his undertaking in the ocean was an enormous success. There was no doubt left that the United States had become a first-tier naval power, a place it continues to hold today.

Strategically, the most significant upshot of the cruise was a shift in the balance of power in the Pacific. Fresh off of major victories against its regional foe Russia, Japan eyed the Pacific as a potential sphere of influence. The cruise of the Great White Fleet proved that Japan may not be as ready for conflict in the Pacific as it once thought. It was one of the major influences contributing to the signing of the Root-Takahira Agreement, in which Japan and the U.S. basically both agreed to respect each other's boundaries in the Pacific (for the time being). Overall, the trip was an unmitigated success: a physical application of Roosevelt's domestic policy and a valuable training exercise for the new navy on the block.

The fleet set the stage for the modern U.S. Navy

The United States Navy has become an entirely different behemoth since the Great White Fleet's tour. Just 45 years after its voyage, the construction of the first nuclear-powered surface ship would begin. Not only was the steam engine long banished from naval operations, but the battleship, too, found itself phased into irrelevance when naval warfare took to the sky with the rise of the aircraft carrier.

Processes, capabilities, and technologies have changed so much that they are virtually unrecognizable to the sailors aboard the Great White Fleet. With no fewer than 11 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, the U.S. now has the most powerful navy on the planet. And while peacetime cruises may have gone out of vogue, agencies of every nation watch the position and deployment of America's naval assets with keen interest.

Alfred T. Mahan's analysis of sea power's role in international relations proves accurate: Any nation with pretensions to superpower status must be prepared to field a competent navy with which to project its power and presence around the globe.