Why More People Listen To Vinyl Records Than CDs

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), vinyl records outsold CDs in the United States in 2023, the second consecutive year for that to happen. This is particularly notable because the 2022 figures marked the first time that this had happened since 1987 — a whopping 35 years. According to the 2023 figures, this covers not just revenue (new records retail for a lot more than new CDs), but also units sold, with 43 million vinyl sales compared to 37 million CDs. That comes as CD sales increased year over year, with an 11% jump from 2022.

If you don't exactly keep up with home audio and only know about the broadest possible strokes of vinyl vs. CD, then you may be asking why this is the case. One of the original selling points of CDs was that they eliminated vinyl-specific problems such as surface noise, ease of damage with resulting audible artifacts, and storage issues. All while having a higher level of fidelity than cassette tapes, the other dominant analog format of the time.

Well...it's complicated.

Those negatives were often exaggerated, thanks in part to low-quality turntables that damaged records. And there are also a lot of people who prefer the sound of a well-made record to that of a comparable CD. That's just scratching the surface, though, and there are a lot of mitigating factors, so let's break it down.

Large format cover art is simply much cooler

This one is purely about looks, but with good reason. If you buy a physical album in a digital era, you want to feel like you're getting your money's worth. While album cover art has become less of a distinct art form in the decades since the original decline of vinyl, there are still plenty of eye-catching new covers released every year, and plenty of vinyl sales come from classic titles. Taken together, it explains why the physical music buyer may want something really nice to look at.

Think about it in terms of raw numbers. A 12-inch vinyl record sleeve (12 inches square or 144 square inches) has nearly six times the area of a five-inch CD cover (five inches square or 25 square inches). Not only does that leave a lot more room for detail, but it's something that you can display on a wall. A beat-up, barely playable record with a cool sleeve in presentable condition retains some value if the cover art is nice enough.

The 12-inch format is so much more preferable from a visual perspective that, even well into the CD era, promotional materials sent to music stores included what are commonly known as promo flats: 12-inch album art from upcoming releases, for display in the front window and on the wall of the store. In this case, it's not really in dispute that bigger is better.

The ritual of vinyl playback is fun and relaxing

This is arguably the least important aspect of the vinyl experience, but it's cited so often in articles about why people prefer the format that it has to be mentioned: That there's a ritual element to playing records that doesn't apply to other formats.

The exact steps depend on the shape that your playback setup takes, but if nothing else, think about how many steps are involved. You have to remove or lift the dust cover from your turntable, pull the record off the shelf, remove the liner and record from the sleeve, remove the record from the liner, place the record on the turntable, lift the tonearm, place the stylus on the record, and turn on the turntable. Midway through playback, you also have to lift the tonearm, flip the record, and return the stylus before turning it back on to listen to side B.

That's setting aside any other steps that might be particular to your model of turntable, but it's involved, and it means that listening to vinyl is something that you have to set time aside to do. It's not the same as passively listening to streams from your phone.

"If I'm listening to a full album, I like to get a pot of coffee ready, a paper or magazine and get comfy in the front room," explained Andy, a vinyl aficionado, in a 2015 BBC article about vinyl rituals. "I lay back and let the music take over."

Sounds nice, doesn't it?

Good turntables have become more affordable

Even as vinyl was booming, the relatively complicated nature of the hardware compared to today's electronics was a noticeable barrier to entry, as was the price of a good turntable. There were — and still are — cheaper record players from companies like Crosley and Victrola, but their quality leaves a lot to be desired. To make matters worse, The Wirecutter's testing in 2020 confirmed the fears that they can easily damage records with their excessive tracking force, and their ceramic cartridges don't help, either.

The price floor for a high-quality turntable was disrupted after the successful, Kickstarter-based launch of U-Turn Audio in 2012. Even as inflation hits our wallets, the barrier of entry has gotten lower: U-Turn's Orbit Basic is $249 and includes the built-in phono preamp stage that some turntables lack, which earned it the status of Wirecutter's best budget turntable. Crosley has expanded its line to include turntables with replaceable moving-magnet cartridges and adjustable tracking force. The Audio-Technica AT-LP60 series – currently the AT-LP60X – has long been a well-reviewed budget pick at just $149, and even the sustainably built House of Marley turntables don't compromise sound while going green at a reasonable price, starting at $149.

Even better? Good speaker options for vinyl are cheaper than ever, too!

There are reasons to think vinyl inherently sounds better

A lot of people who prefer vinyl will tell you that they think it sounds better than CD and many other digital formats. The truth of the matter is complicated, but what most people familiar with the concept probably don't realize is that it's a debate that dates back to the beginning of the CD era in the 1980s.

Veteran music writer and vinyl evangelist Michael Fremer has long claimed, including on his former blog, that he was so dismayed by his initial exposure to CDs, he put a custom bumper sticker reading "Compact Discs Sound Terrible" on his car. Though there's little corroboration for those specifics, Fremer stumping for vinyl over CDs back in the day isn't in dispute. That includes a 1985 letter to the Los Angeles Times, quotes in a 1990 New York Times article, a 1991 feature syndicated by Gannett News Service, a heavily cited op-ed he wrote for Music Connection in 1988, and a 1992 New York Daily News profile. This goes beyond nostalgia.

Are Fremer and his ilk right? That depends on your criteria. Even Fremer conceded in a 2015 blog post comment that his concern is not whether vinyl — or quality analog formats in general — are scientifically measurable as superior. That even if it's harmonic distortion creating a unique sound signature, as it's often described, and not analog being more "accurate" to live music, that's still fine. But it doesn't explain those who claim to distinguish analog-sourced vinyl from digital-sourced vinyl.

The best-mastered version is sometimes genuinely on vinyl

If you've kept up with tech and music media in the past couple of decades, then you've probably heard the term "Loudness War" thrown around at some point. This refers to digital recordings being mastered with excessive amounts of dynamic range compression while pushing the CD format's volume limits, resulting in flat-sounding, often artifact-riddled releases. Vinyl, however, would be physically unplayable if cut that loud.

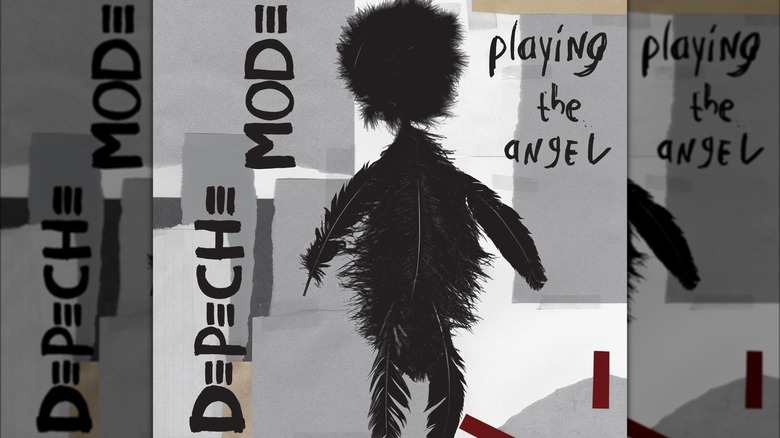

Case in point: Depeche Mode's 2005 album "Playing the Angel" is often cited as one of the worst offenders of the Loudness War, and is included in lists on the topic's TV Tropes page. The Dynamic Range Database listing for the original CD gives it a dismal score of five, meaning there was just a five-decibel difference between the peak and average levels. Some songs scored as low as two. A digitized copy of the vinyl release scored a much more pleasant-sounding 10, just below the 11 average of the SACD release it appears to have been sourced from. If you want to hear the album as intended, opt for the SACD or vinyl over the CD and releases sourced from it.

Loudness War aside, there's the simple fact that many modern vinyl releases, especially reissues, are intended for an upscale audiophile audience. Exceptional care is taken with the mastering, as is described in detailed sources notes provided by reissue labels like Intervention Records.

A lot of music on vinyl is not available on CD

If you're familiar with Rock and Roll Hall of Fame class of 1998 inductees Fleetwood Mac, it's most likely from their late-1970s albums: "Fleetwood Mac," "Rumours," and "Tusk," with "Rumours" being famous for addressing gossip about the band members head-on. What you may not be aware of is that Fleetwood Mac started as a British blues band in 1967, with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joining in 1975.

Buckingham and Nicks had released their own album, a self-titled effort under the name Buckingham Nicks, in September 1973, less than two years before the release of their first album with Fleetwood Mac. It's a great album that would fit perfectly into the Fleetwood Mac catalog — but it's never been officially released on CD or any other digital format. Why? Based on an interview that Nicks gave to NME in 2020, it's simple: Going back 45 years to 1975, the first time a re-release would have made sense, the duo, who jointly own the rights, could never agree on if they wanted to reissue the album.

"Buckingham Nicks" may be the most notable example of vinyl-era titles without digital releases, but it's far from alone. Numerous extended remixes of disco and new wave songs from the '70s and '80s are vinyl-only. So is the bulk of the catalog of power pop legend Jack Lee. And Depeche Mode's cover of Sparks' "Never Turn Your Back on Mother Earth." Among many, many others. So get hunting.

Collecting vinyl helps broaden your taste in music

As useful as algorithmic music recommendation systems can be, their purpose is not to broaden your taste in music. Instead, they will recommend artists that fit your existing tastes. This isn't a bad thing in and of itself, but if you enter Spotify, Pandora, or whatever other service you prefer as someone who primarily listens to alternative rock, that's what will be recommended to you. If you're feeling more adventurous, it's not ideal.

Collecting vinyl, on the other hand, often helps the listener expand their taste to other genres. There are a multitude of reasons why. One that's pretty simple is that once you've invested in a quality vinyl playback system, you'll be inclined to start looking for records that show off how good that system can sound, and that often leads to genres further afield than pop and rock, like jazz, blues, and even classical.

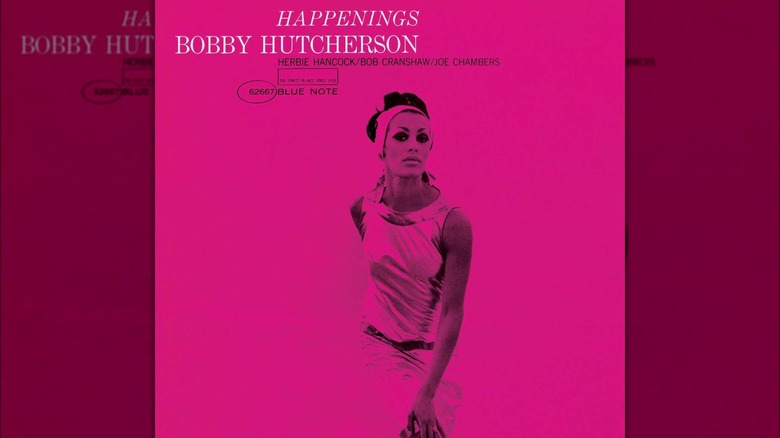

Another reason is that the vinyl-purchasing process lends itself to discovery. Given the size of vinyl records and the ever-increasing costs of postage, this even extends online, as it's always worth looking to see if someone selling a record you want has other things you might be interested in. But it primarily applies to the in-store experience. Maybe you find yourself digging through unsorted crates of new arrivals or heavily discounted records. Perhaps you flip through everything and your eye is caught by the beautiful sleeve art on classic jazz records from labels like Blue Note and CTI. Soon enough, you'll be a snob.

There's a culture around vinyl that doesn't exist with CDs

While it's not perfect, there is a genuine sense of culture and fandom around the vinyl format. Generally speaking, you're a lot more likely to find a record store than a CD store, or even a store carrying CDs, period. Record fairs are held everywhere, with nonprofit radio station WFMU's annual fundraiser in New York City among the best-known, but when have you ever heard of CD fairs?

Granted, some of this is just practical. Lossless compressed music has become commonplace on both digital music stores and all-you-can-eat streaming services, so unless you're dead set on physical ownership or seek out music that hasn't been licensed for download or streaming, you can get an identical-sounding track online. Vinyl is a distinct product that can't be replicated that way.

Regardless, there's a sense of community around vinyl that doesn't exist with CDs. Not only are there record-centric spaces that don't exist for CDs now, but record stores are often devoted to used records with turntables and headphones available for demo purposes. This means that you'll inevitably end up sitting or standing next to another shopper, and perusing each other's stacks of tracks.

There's also much more of a community around vinyl online, with Reddit's /r/vinyl constantly bustling and many highly trafficked old-school message boards devoted to the topic. Among the more popular haunts are Vinyl Engine, Vinyl Collective, and the Steve Hoffman Music Forums, plus blogs like Tracking Angle — Michael Fremer's current home.

If you need to get rid of vinyl, it's easier to find a buyer

If you're still buying CDs, outside of very specific outliers like BOOKOFF in New York City, you're not likely to find stores that will buy them in bulk if you want to get rid of them. Some limited editions might be of particular interest, but you'll probably need to sell them online, usually piecemeal. With vinyl records, though, record stores are constantly buying large collections to absorb into their inventory. You might not necessarily get what you paid for them, but finding a buyer is trivial unless you're trying to offload a collection of particularly common and undesirable records.

This can also extend to getting resale value out of individual releases. As noted earlier, a lot of newer vinyl releases are from specialty reissue labels. These require licensing the titles individually from the rights holder, and much of the time, once they're gone, they're gone. Occasional big sellers might be worth keeping in print, but those are outliers. If a particular reissue becomes a big favorite, its value can skyrocket on the secondhand market.

Case in point: Sea Change, Beck's 2002 album, got the deluxe treatment from Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab in 2010, and according to Michael Fremer's contemporaneous review, it sounds amazing. Within a few years, the $39.99 retail reissue sold out, and now? As of this writing, the most recent eBay sale went for over $300, while the dozen Discogs listings for it start at around $200. Collectibles are volatile, but at least vinyl is collectible.